“If the Spirit of the Original Is to Be Retained”

“If the Spirit of the Original Is to Be Retained”: Ways of Seeing Camerawork

By Samuel Bibby

Abstract

For perhaps as long as they have been the focus of scholarly attention, periodicals as objects have always posed a challenge to those trying to convey their understanding of them to an audience, be it in the three-dimensional space of a museum display or in the two-dimensional context of a photographic reproduction printed on a page. Conventionally, in each instance only a single opening—two facing pages of a magazine—can be presented to the viewer at any one time, a condition determined by the physical nature of the codex format: the bind of the bound. Charting the range of strategies that have been employed to try to overcome—or at least compensate for—this furnishes us with the chance to reflect on what producing periodicals means today, both as a historical subject and as a contemporary practice. As part of this historiographical endeavour, the intersection of the fields of periodical studies and digital humanities provides a useful opportunity to think through the various questions that such printed material engenders. How were periodicals used in the past? How are those same periodicals used today? And how are they employed now to understand how they were then? How too might such layers of use (and meaning) be captured and conveyed? In this article I seek to address such issues through looking at a single case study, the photographic magazine Camerawork, which was produced in Britain between 1976 and 1985 by members of the Half Moon Photography Workshop.

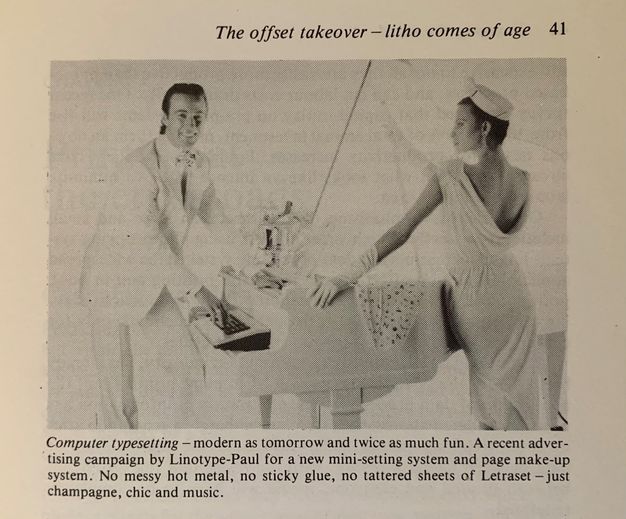

Thumbing through Alan Marshall’s 1983 book Changing the Word: The Printing Industry in Transition, its readers encounter the grainy black-and-white reproduction of a photograph portraying a couple both fashionably attired entirely in white and flanking a likewise white grand piano (fig. 1). Almost immediately, one notices the emphasis on surface and touch: the folds of the back of the woman’s dress, for example; her left hip nestled in the curve of the instrument’s lacquered form; the piece of speckled fabric casually draped over its edge; her gloved and outstretched left hand balanced almost exactly in the centre of the image. The man, meanwhile, is seen extending his right hand as if to operate manually a keyboard device positioned in place of the piano’s usual black and white keys, his left hand resting before a just discernible ice bucket. Marshall’s overall argument, which appears in a chapter on the rise during the 1960s and 1970s of the printing technique of offset lithography, is that the development of such technology needs to be understood within the wider context of the information industry, and in particular in relation to the concomitant restructuring of labour engendered by such innovation. Beneath the image, Marshall furnishes us with a discursive caption: “Computer typesetting—modern as tomorrow and twice as much fun. A recent advertising campaign by Linotype-Paul for a new mini-setting system and page make-up system. No messy hot metal, no sticky glue, no tattered sheets of Letraset—just champagne, chic and music”.2 The conditions of production, the material reality of labour, the image suggests, have been rendered outmoded, giving way to modernity and pleasure, ease and luxury, simplicity and glamour. Such content, however, seems intentionally at odds with the form of the photograph’s reproduction, its own appearance on the page of Changing the Word still redolent of exactly the qualities supposedly eradicated by phototypesetting. Equally, the evident sarcastic tone of Marshall’s caption seems to belie a scepticism on his part about the alleged merit of such technological progress, and by contrast surely implies the importance of figuring the messy, sticky, tattered actuality of print production into any historical account of the time. But I want to suggest that, at a remove of some forty years, it should similarly gesture to the conditions of any such material’s consumption in our own contemporary moment, to the still inextricable relationship between technology and labour underpinning any present-day historiographical endeavour, and prompt us to ponder specifically what is at stake in the differing ways in which the historical material required to produce an account of that period has since been mediated and remediated. For the scholar of periodicals, my focus here, what constitutes their archive? And how do they variously engage with it? In an age of digital supremacy, not to mention following a global pandemic, such questions have perhaps become all the more pertinent. But surely more urgent, it seems to me, is thinking through why they should matter. Put another way, what are the stakes of subjecting the methods of periodical studies to scrutiny?3

2

Periodicals are inscriptions of collective labour, including that of those who have written, edited, designed, printed, distributed, and read them. Similarly, as they move into various spaces of study, from physical museums, libraries, and archives to the virtual realms of online databases, catalogues, and reading platforms, periodicals often index traces of the labour needed to ensure their presence in such contexts. Indeed, processes of mediation and remediation—a key concern in this article—leave their mark on magazines but, crucially, also prompt particular patterns of labour, while in turn denying others. For instance, in a recent analysis of the digitisation of little magazines, Eric Bulson has drawn attention, on one hand, to “the stubborn persistence of a human agent and the materiality of an original object” and, on the other, to the fact that “elements of the more sensuous communion with the object are lost” as the result of such acts.4 Meanwhile scholars of Victorian (above all, literary) periodicals such as Laurel Brake, Linda Hughes, and James Mussell have led the way in questioning the modes by which contemporary readers engage with such material, often championing, for example, practices of looking, moving, and thinking sideways or of browsing and its role in “facilitating serendipitous research through page turning”.5 My intention here is to marshal such work and ideas in relation to conventional art-historiographical methodology, and to reflect on how the different apparatus by which art history comes to be mediated and remediated contributes to (and impinges on) the meaning of magazines.

4For perhaps as long as they have been the focus of scholarly attention, periodicals as objects have always posed something of a challenge to those trying to convey their understanding of them to an audience, be it in the three-dimensional space of a museum display or in the two-dimensional context of a photographic reproduction printed on a page.6 Conventionally, in both instances only a single opening—two facing pages of a magazine—can be presented to the viewer at any one time, a condition determined by the physical nature of the codex format: the bind of the bound.7 As technologies, the vitrine and photography each in its own way flattens and stills something that not only has depth but is also inherently dynamic, not to mention removing it from the possibility of being directly handled, which is after all an integral part of a printed magazine’s original form and function. Charting the range of strategies that have been employed to try to overcome—or at least compensate for—the bind of the bound furnishes us with the chance to reflect on what producing periodicals means today, both as a historical subject and as a contemporary practice. As part of this historiographical endeavour, the intersection of the fields of periodical studies and digital humanities, the genesis and evolution of which are broadly concurrent, provides a useful opportunity to think through the various related questions that such printed material engenders. How were periodicals used in the past? How are those same periodicals used today? And how are they employed now to understand how they were then? How too might such layers of use (and meaning) be captured and conveyed? In what follows I seek to address such issues through looking at a single case study, the photographic magazine Camerawork, which was produced in Britain between 1976 and 1985 by members of the Half Moon Photography Workshop. The clues suggested by the interplay between touch and surface so evocatively invoked in the Linotype-Paul advert offer at least one path by which to navigate such art-historiographical terrain.

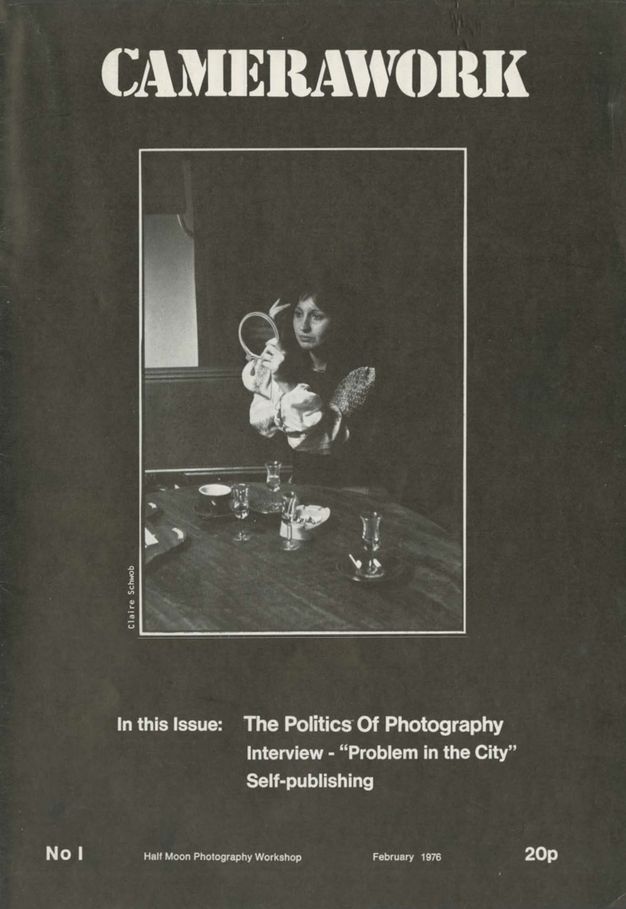

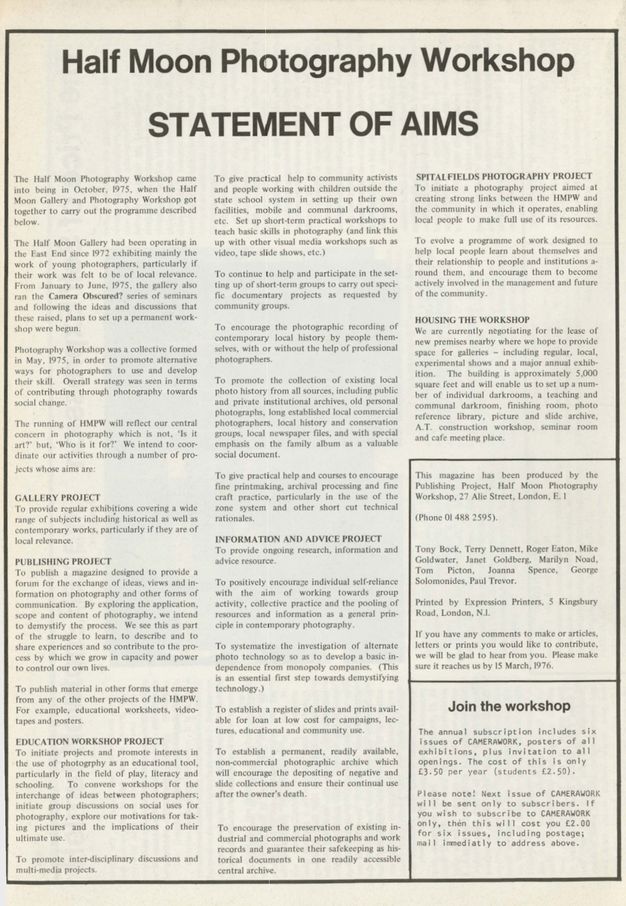

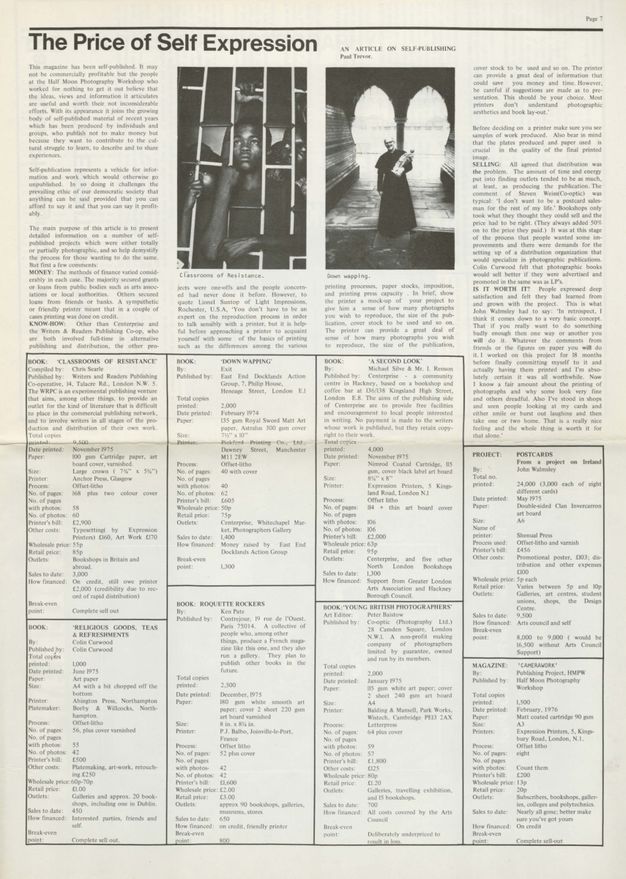

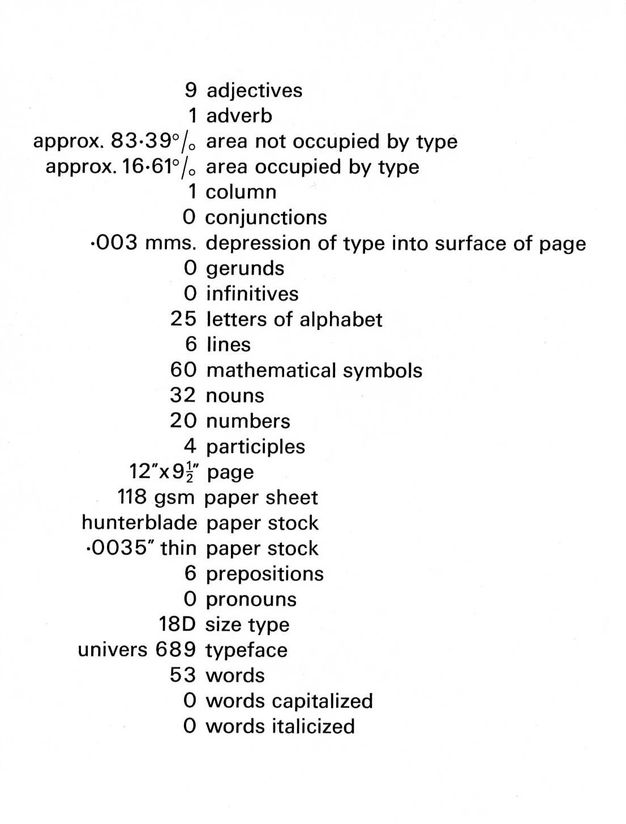

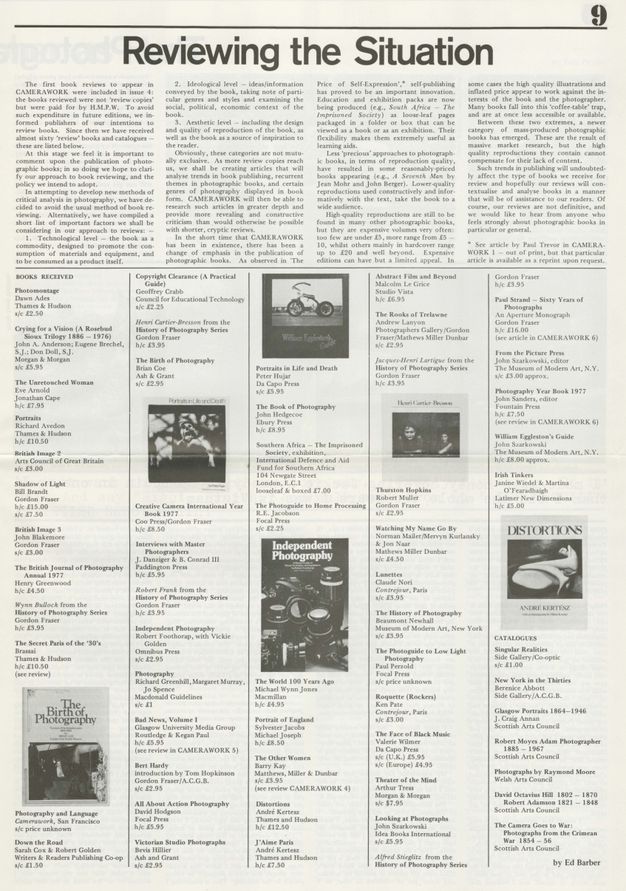

6First, some brief historical background: the collective that produced Camerawork, the East London-based Half Moon Photography Workshop, had come together in late 1975, and by the beginning of the following year had published the first issue of the magazine (fig. 2), just one element of their larger programme.8 A “Statement of Aims” on its back cover (fig. 3) made their intentions for Camerawork explicit: “To publish a magazine designed to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas, views and information on photography and other forms of communication. By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process. We see this as part of the struggle to learn, to describe and to share experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives”.9 In that same inaugural issue of February 1976, collective member Paul Trevor revealed many of the specific conditions of the magazine’s production. In a piece entitled “The Price of Self Expression: An Article on Self-Publishing” (fig. 4), after providing a guide to structures of funding and the expertise necessary to produce one’s own photographic publication, Trevor taxonomically catalogued the salient details of a range of such projects, predominantly books, including Down Wapping, which had been made by members of the Exit Photography Group (of which he himself was a member) and had appeared two years earlier.10 The final publication detailed was none other than Camerawork itself. We learn, for instance, that the print run was 1,500, that it was printed on 90 grams per square metre matt coated cartridge A3 paper using offset litho by Expression Printers in Dalston. Structured in a way that is reminiscent of conceptual artist Dan Graham’s well-known Poem Schema from the previous decade (fig. 5), some of Camerawork’s physical and material qualities, together with financial information and details about its distribution, can begin to give us a picture of how the eight pages of what readers held in their hands had been made.11 Trevor’s awareness of his audience is twice made explicit here: first, in his entry for the number of pages with photos (“Count them”, he instructs); and, second, in detailing sales to date (“Nearly all gone”) in his playful advice to “better make sure you’ve got yours”.12 The publication’s title is set in a typeface distinct from the text surrounding it, the sans serif used elsewhere on the page solely for image captions, as if to suggest that what appears beneath it should be seen as some form of reproduced representation, a textual mise-en-abyme even. Reflexivity regarding publications evidently remained a concern; in a piece entitled “Reviewing the Situation” from issue 7, published in July 1977 (fig. 6), fellow collective member Ed Barber set out a thematic framework whereby books being reviewed in the magazine should be evaluated, specifically on technological, ideological, and aesthetic levels. It is more than tempting to subject Camerawork to its own criteria: “as a commodity, designed to promote the consumption of materials and equipment, and to be consumed as a product itself”; by examining its “social, political, economic context”; and taking into account its “design and quality of reproduction”.13 But all in good time.

8

Conventional art-historical (if not always art-historiographical) method might have us address the magazine in relation to others at this point, both those broadly contemporary to and those preceding it. To be sure, Camerawork is ripe for art-historical treatment not only in terms of the photographic material that it reproduced,14 but also as an object deserving attention in its own right. Indeed, the publication can be profitably considered in visual and material relation to any number of the constellation of periodicals from both its past and present, by situating it in what I have elsewhere termed its “periodical landscape”, a framework drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of the cultural field whereby the meaning of new magazines (and indeed their subsequent histories) can be fully discerned only by positioning them alongside and in relation to other serial publications.15 In many ways, doing so mirrors the methods that must have been employed by those involved in the formation of magazines like Camerawork at the time. Discussing design process in their instructional book Into Print: A Guide to Publishing Non-Commercial Newspapers and Magazines, which appeared in 1975, Harold Frayman, David Griffiths, and Chris Chippindale proposed that “the best way to learn is probably to look critically at as many papers and magazines as you can”.16

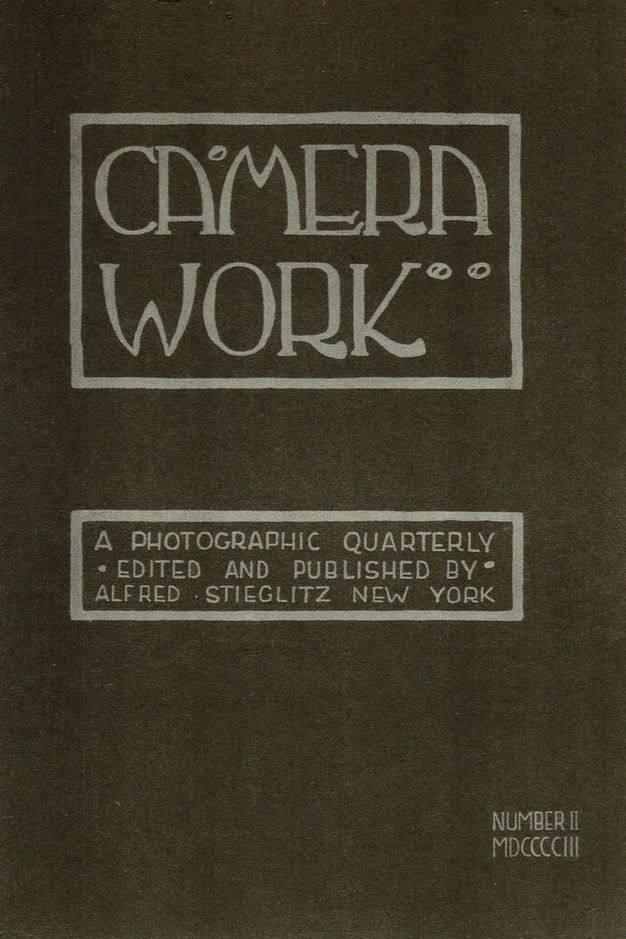

14In terms of Camerawork’s subject matter, we might, for instance, consider it in conjunction with the journal History Workshop, dedicated to “history from below” and founded that same year.17 It can similarly be thought of in relation to any number of self-published, community-generated (and community-focused) publications such as The Islington Gutter Press.18 It could also be seen alongside other contemporary magazines dedicated to worker photography, such as Arbeiterfotografie, or to earlier titles from the illustrated press known for their inclusion of documentary material, say Picture Post or Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung.19 In terms of its emphasis on photographic practice, meanwhile, magazines such as Creative Camera and Album, to name but two, warrant mention.20 And then, of course, from earlier in the century, there are potential allusions to and comparisons with its virtual namesake, Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work (fig. 7), nominally distinct thanks to the earlier incarnation’s (only sometimes explicit) space between the two parts of its title. Founded in New York in 1903 and designed by fellow photographer Edward Steichen, Camera Work represents something of a watershed in terms of magazines dedicated to photography, in particular in terms of how it mediated its content and how, as a multiply-reproduced object, it reproduced multiply-reproduced objects.21 Having noted the inherent challenges in such an enterprise, Stieglitz and his fellow editors writing in the first issue urged: “It is, therefore, highly necessary that reproductions of photographic work must be made with exceptional care and discretion if the spirit of the original is to be retained, though no reproductions can do full justice to the subtleties of some photographs”.22 To ensure the integrity of its subject, the labour of the photographer, we would do well to remember, has to be matched by that of the magazine’s editors, designers, and printers, among others.

17

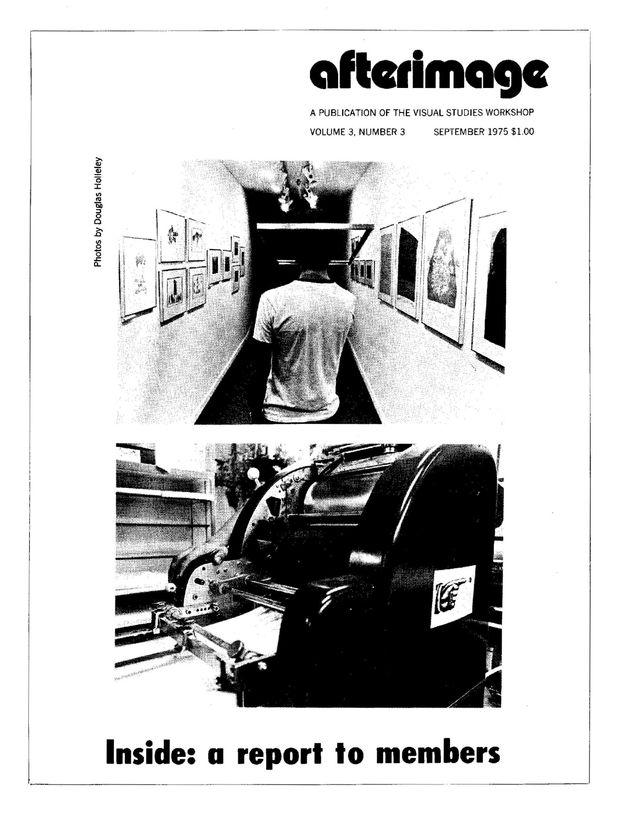

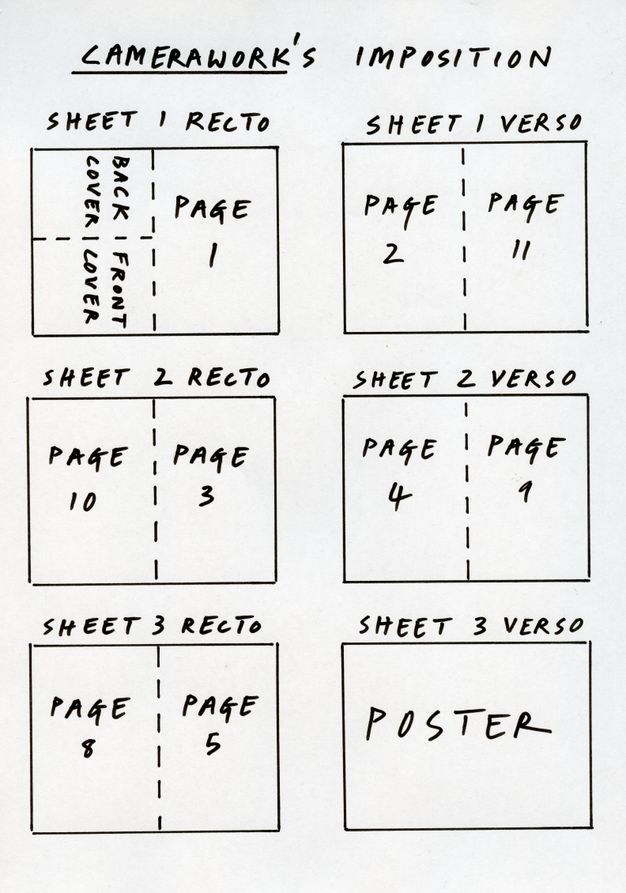

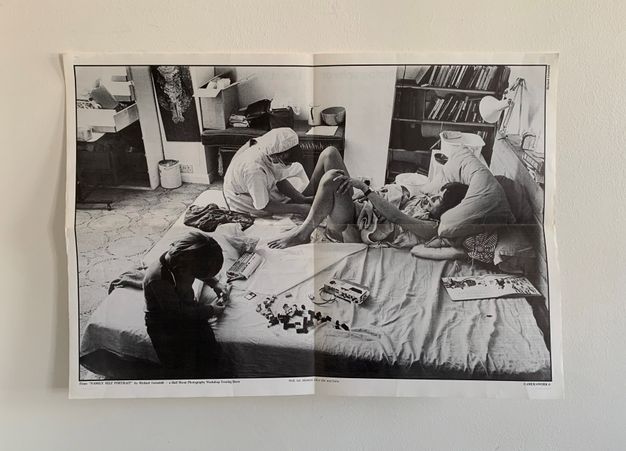

Such attention to production, to the materiality and visuality of the periodical, can prompt us to return to the 1970s and contemplate, alongside Camerawork, other magazines with which explicit relationships might be forged in terms of their physical form, not to mention the processes (both technical and, for that matter, social) by which such publications were produced. At this juncture I need to reveal a key piece of information concerning Camerawork thus far held back, although I hope not disingenuously. Unlike every other magazine we have seen so far, all of whose pages have been, broadly speaking, conventionally bound on the left-hand side to create a codex, Camerawork does not adhere to this format. My reason for omitting to draw attention to this until now is to highlight how easily it can fall by the wayside or slip unwittingly between one’s fingers. But doing so obscures what I contend is a vital element of this magazine’s efficacy. Apparently directly modelled, at the suggestion of collective member Tom Picton, on the American photography magazine Afterimage, produced by the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York (fig. 8), Camerawork was printed on a gathering of unbound sheets of A2 paper and then simply folded twice to form what, in the technical terms of bibliography, is referred to as an A4 “loose quire”, assembled with a French or cross fold.23 Beyond the brief prose description just offered, this may be illustrated in a handful of different ways: for example, by constructing a two-dimensional diagram of its imposition, a visual manifestation of the schematic arrangement of the constituent pages (fig. 9). Alternatively, and perhaps more effectively, it can be conveyed in a short home-made demonstration video, captured thanks to the now everyday technology of the hand-held smartphone, and a relatively inexpensive copy of the magazine purchased on eBay (fig. 10).24 Opening and then turning the pages of a copy of issue 6 shows us the range of types of material published by Camerawork: for instance, an article by John Berger on Paul Strand, and pieces on photos of factory workers, on a workshop about children and photography that the collective had organised, and on different equipment and techniques. One of the motivations for this relatively novel format was its ability to include a full A2 page reproduction of a photograph, a feature directly modelled on Afterimage,25 with the pretty obvious intention of furnishing Camerawork’s beholder with something they could go on to display themselves (fig. 11).26 Perhaps just a natural extension of the already well-established relationship between magazine and gallery,27 with the arrival of conceptual art these once discrete spaces had become (even) more indistinct,28 as topically exemplified by the title Umbrella, “unfolding the visual and lively arts from Scotland and the world”, a magazine produced by the Richard Demarco Gallery from 1972.29 But in this particular case there appears to be more afoot, or rather more to get to grips with, to grasp.30 To allow my argument to unfold, I would like to embark on a historiographical survey to look at how people have (or seemingly have not) looked at Camerawork over the years, at how they have mediated and remediated it.31

23

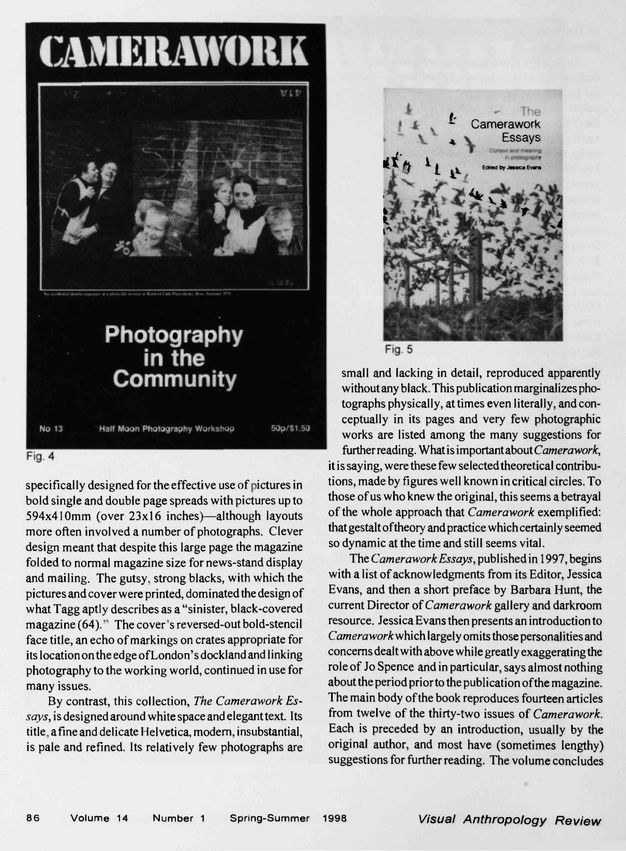

One of the ways in which readers come to so many influential periodicals is via the genre of the anthology, and Camerawork is no exception (fig. 12).32 With the standard framing devices of editor’s introduction and thematic essays, Jessica Evans’s The Camerawork Essays: Context and Meaning in Photography, published in 1997, reproduces fourteen articles that had originally appeared in the magazine, but not as they had originally appeared; instead, it retypesets them homogeneously, thereby erasing vital data.33 In “The Repackaging of 1970s British Photography”, a review of Evans’s edited volume published in 1998 by the journal Visual Anthropology Review, Peter Marshall drew a distinction between, on one hand, the “gutsy, strong blacks, with which the pictures and cover were printed”, and its “reversed-out bold-stencil face title, an echo of markings on crates appropriate for its location on the edge of London’s dockland and linking photography to the working world”, and, on the other hand, the anthology, “designed around white space and elegant text. Its title”, Marshall opined, “a fine and delicate Helvetica, modern, insubstantial, is pale and refined”.34 Reproducing images to scale of the two side by side served to foreground his dissatisfaction (fig. 13). “Too often anthologies wrench their materials from the original site of their production”, Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock declared in the introduction to their 1987 book Framing Feminism. “By reproducing articles in facsimile form”, they continued, “we want to give a concrete representation of the time, space, intentions and constraints that initially determined the texts. The facsimile form allows us to discern in residual form the living movement of history”.35 As will become apparent, the nature of such a movement resides not only in the magazine’s visuality but also in its materiality, in the way in which Camerawork itself as an object was made: to move and to be moved. Such a point begs emphasis; so very often the inherent mobility of a periodical and its constituent pages stares us in the face, as the Forschergruppe Journalliteratur logo, for example, makes all too clear (fig. 14). And yet such a condition, and the elements of design that emerge and extend from it, can all too easily become visually flattened, technologically stripped away from cultures of reception, the visual economies of their reproduction, and historiographical consumption.

32

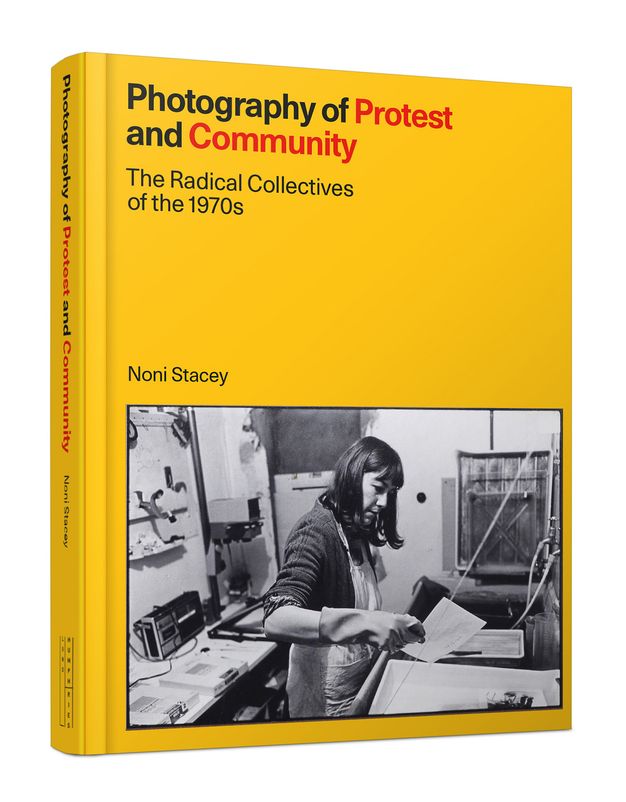

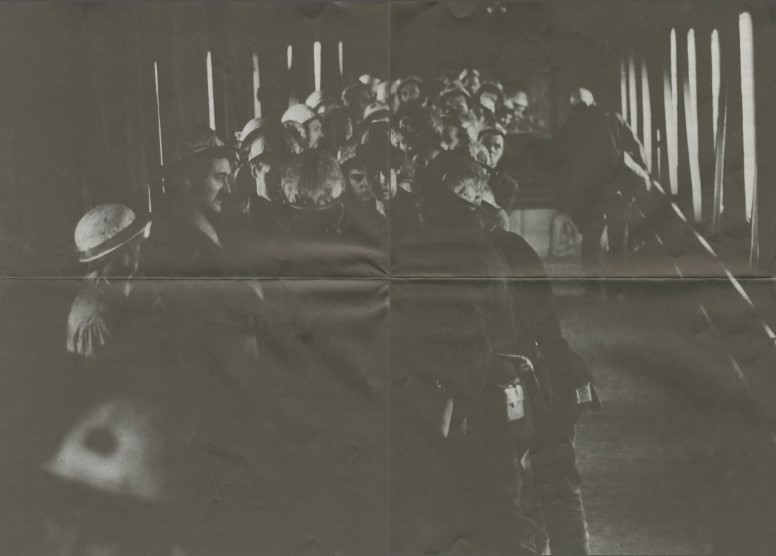

More recently, Camerawork has received historical attention in Noni Stacey’s Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s, published by Lund Humphries in 2020, and promoted using product photography emphasising its three-dimensional nature as an object (fig. 15). Situating Camerawork thoroughly within the wider context of the Half Moon Photography Workshop’s broader endeavours, Stacey reproduces a range of material that originally featured in the magazine; however, beyond a couple of front covers, most visual context is sadly shorn from the images in question (fig. 16).36 A case in point is a work by the American photographer Robert Golden, originally included in issue 3 of the magazine as the central A2 poster (fig. 17), as part of an interview with him conducted by Jo Spence, first captioned as showing “Overleaf: Kellingley colliery, Yorkshire / discussion before the shift”.37 Ably discussed by Stacey in relation to the imagery of labour, Golden’s photograph is nevertheless re-presented to Stacey’s reader devoid of any trace of the original material conditions in which it would have been beheld by someone physically turning the pages of Camerawork back in July 1976 or at any point since (fig. 18).38 Ironically, however, the version of her book used in the writing of this article is a PDF of an uncorrected proof, provided by the publisher as a review copy and inscribed with a digital watermark, rendering visible vestiges of an important stage in the work’s own production process not afforded to its own subjects.

36

Where reproductions of reproductions (in facsimile or otherwise) run the risk of falling short is, of course, often determined by the physical parameters or limitations of the medium in which they subsequently appear. Exhibitions, however, afford the opportunity to foreground “originals”, albeit ironically in this particular instance given that the displayed magazines are not only multiples but also reproduce photographs that are already reproduced multiples themselves. Installation photographs taken at the 2011 exhibition Pages from a Magazine: Camerawork, staged at the gallery White Columns in New York, document the presentation of one person’s collection of the publication (fig. 19 and 20).39 The bound codex has never lent itself easily to exhibition display: more often than not, a single opening of any given volume has to be privileged over all others, the work rendered immobile and affording only a partial view of its contents.40 Here, however, Camerawork’s relatively unusual unbound nature permits a degree of simultaneity: Richard Greenhill’s “Nell, ten minutes after she was born” from his Family Self Portrait, the A2 poster in issue 6, can be seen (as originally intended) pinned to the gallery wall as part of a display including, for instance, a page from Victor Burgin’s 1976 essay “Art, Common Sense and Photography”, the fold through the middle still discernible, and with a facsimile of the verso visible on the wall beneath. Meanwhile, on the perpendicular wall can be seen the particularly apt guide to do-it-yourself exhibition-making from issue 10.41 Beyond installation photographs, moreover, there are many other ways in which exhibitions can be recorded for posterity, not least in catalogues. However, when the subject is magazines, relationships between the two types of publication—subject and object—have the potential for fluidity and/or slippage.42 For an example, one can turn to a recent exhibition on Bill Brandt and Henry Moore. As Yale University Press’s promotional YouTube video for its catalogue makes clear (fig. 21), there are a number of reproductive modes by which residues of the “dimensional, embodied encounter” of holding photographs, such as those from the pages of Picture Post, can be subsequently captured and conveyed.43

39

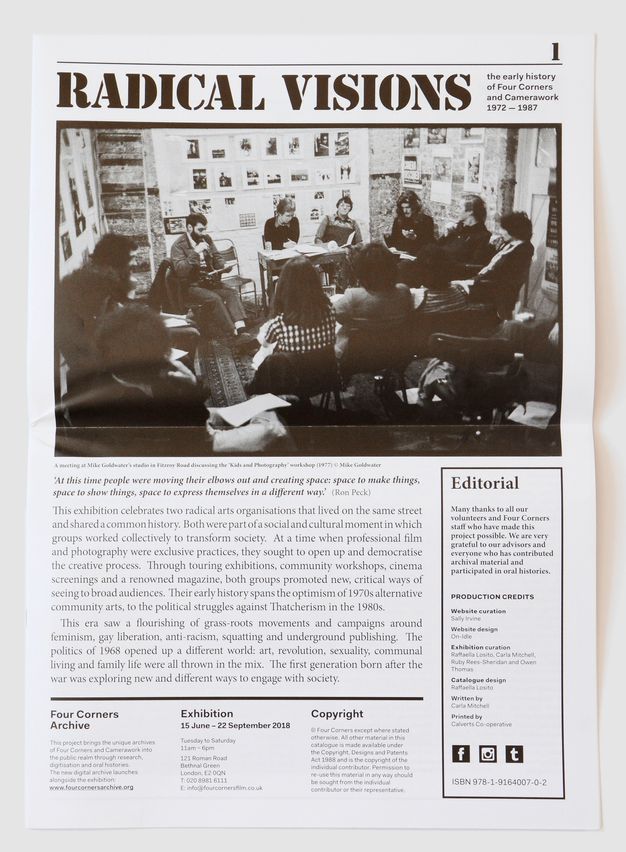

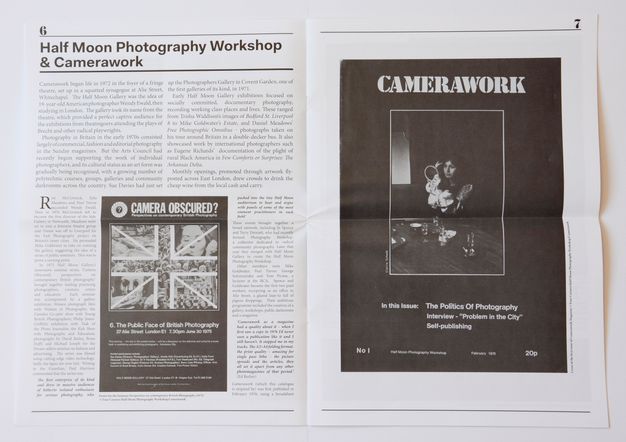

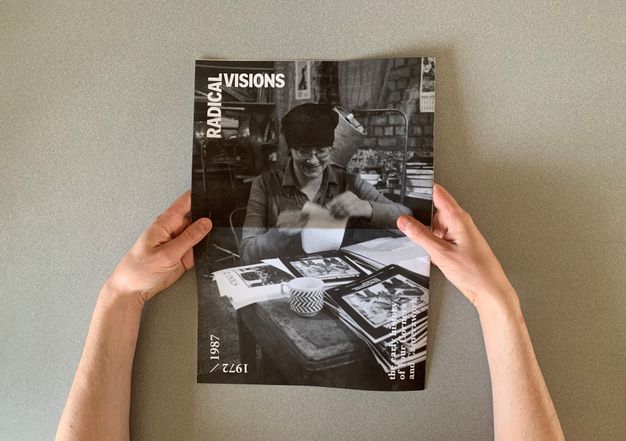

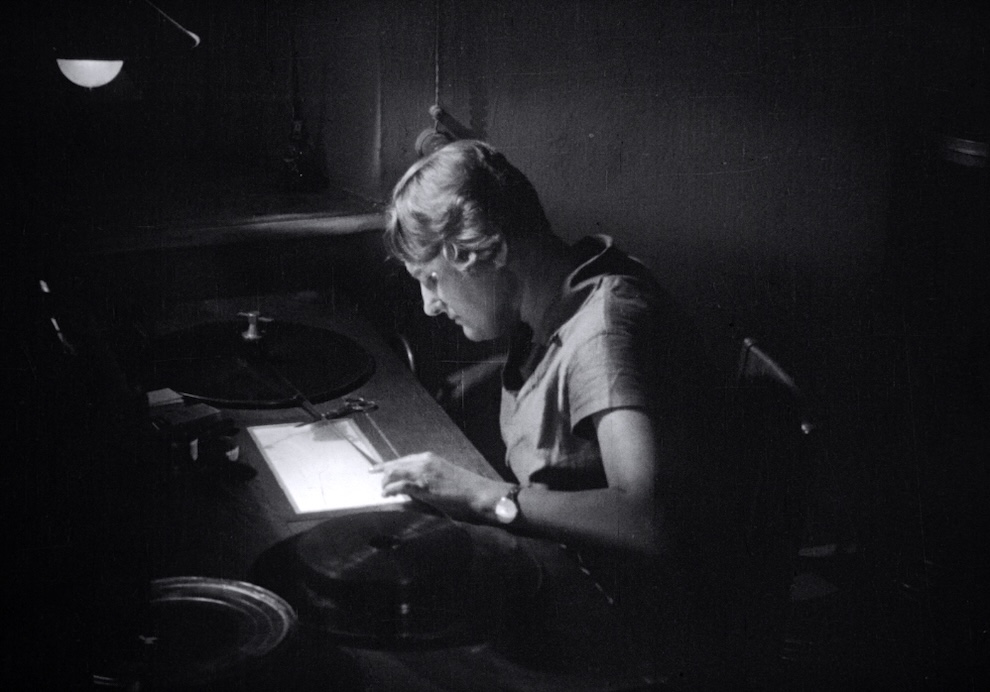

The exhibition Radical Visions, mounted by the gallery Four Corners in 2018, is by far the most sustained attempt in recent years to provide an account of Camerawork, and coincided with the launch of the organisation’s digital archive platform. Its twenty-page catalogue, written by Carla Mitchell, designed by Raffaella Losito, and printed by Calverts Co-operative (fig. 22), sets out to record the contents and intellectual thrust of the show—a display that consisted of a mixture of pages of the magazine (both original copies and facsimiles) and archival material hung on walls and contained in vitrines, as photographs of the exhibition’s opening attest (fig. 23). A four-page essay in the catalogue charts the genesis of the magazine through a conventional combination of text and image (fig. 24). At the bottom right of its first page readers behold an indented block quotation, a descriptive passage by collective member Ed Barber: “Camerawork as a magazine had a quality about it—when I first saw a copy in 1976 I’d never seen a publication like it and I still haven’t. It stopped me in my tracks. The A2>A4 folding format, the print quality—amazing for single pass litho—the picture spreads and the articles, they all set it apart from any other photomagazines of that period”.44 The facing page is given over to a reproduction of the first issue of Camerawork in all its glory: the cover featured a photograph of a woman looking at herself in a hand-held mirror by Claire Schwob, almost as if self-reflexivity were the first message the magazine wished to convey. Following Barber’s testimony, Mitchell’s text explains that “Camerawork (which this catalogue was inspired by) was first published in February 1976, using a broadsheet”,45 at which point, mid-sentence, the reader must take the bottom outside corner of the facing page bearing the cover between their index finger and thumb and turn it over, almost as if (although not quite) opening that which has been printed on it (fig. 25). Immediately, before returning to the as yet uncompleted sentence, one’s eye is drawn to the largest of the photographic images reproduced on this subsequent double-page spread, a black-and-white shot positioned at top left.46 It is almost as if the catalogue’s beholder temporarily joins the group of four figures depicted in the reproduced image, all of whom are looking at proposed layouts for an issue of the magazine, as a caption to the side of it confirms. The reader becomes a witness to, even a participant in, the processes of labour required to produce the historical subject at hand being contemplated. As if to perpetuate this focus, just below it the unfinished sentence carries on, intriguingly in a way that almost renders its first part on the previous spread unnecessary: “format—sheets of A2 paper folded to A3, then to A4”. As the paragraph continues to unfold, more details of the publication’s production are revealed: “The magazine was put together at a marathon all-night session in [Mike] Goldwater’s studio in Chalk Farm, fuelled by coffee and beigels. Volunteer Marilyn Dalik Noad [sic] worked through the night on a borrowed golf ball typewriter to typeset the galleys, while others did the paste up”.47 The foregrounding of labour, meanwhile, continues. On the facing page of the Radical Visions catalogue, itself bisected by the publication’s own fold, is a further photograph taken by Mike Goldwater, of what is referred to as a “folding session” for issue 6 of the magazine. Jo Spence, Shirley Read, and Ed Barber are seen among pile upon pile of pages of the magazine, perhaps even the very ones that I manipulated earlier in my first video; some already folded, gathered, and assembled; others laid out on the table in readiness; another still clasped between Spence’s hands. My reason for belabouring this emphasis on folding shall shortly become clear.48 Turning to the outside back cover of the magazine-inspired catalogue, this manual process can be discerned in closer detail.49 Here Spence is seen at close hand, in the spring of 1976, at work assembling the second issue of Camerawork for distribution. Again, her act of folding—movement rendered all the more palpable by its blurred focus—is reinforced or accentuated by the fold through the middle of the sheet on which the photograph has been printed, the two intersecting at the very centre of the page in marked contrast to the nonchalant begloved idleness of Linotype-Paul, while the hands of the catalogue’s reader physically bracket those of Spence (fig. 26), as if thus joining her and somehow participating in the same labour in which she is so cheerfully engaged.

44

This image is just one of countless others documenting the making of the magazine (fig. 27), physically deposited in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute, that have been digitised and made freely available via the Four Corners website, together with the oral histories from which Mitchell drew to create her catalogue essay.50 Of course, what such photographs, inscribed by the labour that produced them, reinforce is the centrality to Camerawork of the group participation that brought it into being. As the magazine’s “Statement of Aims” made clear, one of its goals was “to positively encourage individual self-reliance with the aim of working towards group activity, collective practice and the pooling of resources and information as a general principle in commercial photography”.51 Nowhere is this more tangible than in the folding sessions at which members of the Half Moon Photography Workshop came together to bring the magazine together, a gathering for gathering. But I suggest that such a collectivity did not stop there, for it is precisely the unbound, twice-folded nature of Camerawork that lends this particular periodical its greatest impact. As a result of this unconventional format, the labour of its collective facture itself becomes enfolded into the materiality of the magazine and remains a latent potential until its pages are then unfolded by the subsequent labour of the beholder. Sceptics may be tempted to account for Camerawork’s loose quires as having been dictated by financial necessity, a perennial issue of course. For example, in a 1978 article on setting up one’s own socialist newspaper published in the magazine Wedge, Kevin McDonnell lamented: “Some papers suffer more than others, being reduced, for instance, to collating by hand. There are few tasks which rival this in pure, unadulterated tedium”.52 For Camerawork, I want to stress, such material circumstances were born not out of constraint but rather from the political desire to empower their audience. Writing in 1972, Clifford Burke suggested that operations such as collating and folding “tend to be overlooked in the planning and preparation of printed work, because they can be tedious and not nearly as exciting as designing or laying out the job”.53 By contrast, in Camerawork such elements of the magazine’s production remained at the forefront of the collective’s conception of the publication precisely for the opportunities it offered to envelop its beholders within its material politics.

50Materiality can be seen here as the interplay between an object’s physical characteristics and their signifying strategies. As Katherine Hayles has argued, it is a dynamic quality that emerges from the relationship between, on one hand, physical artefacts and their conceptual content and, on the other, the interpretive actions of their beholders.54 Lying at the heart of such an approach to materiality, I contend, is the enactment of labour. For Johanna Drucker, “performative materiality suggests that what something is has to be understood in terms of what it does, how it works within machinic, systemic and cultural domains”.55 “It shifts”, she continues, “the emphasis from acknowledgement of an attention to material conditions and structures towards analysis of the production of a text”.56 Evidence of such labour can, of course, be inherent in an object that functions as a “self-conscious record of its own production—one laden with specific ideas about the ways in which a [work] can embody an idea through its material forms”,57 exemplified, say, by sequences in Dziga Vertov’s 1929 film The Man with a Movie Camera showing the director’s wife, Yelizaveta Svilova, editing the film that the viewer is subsequently watching (fig. 28).

54

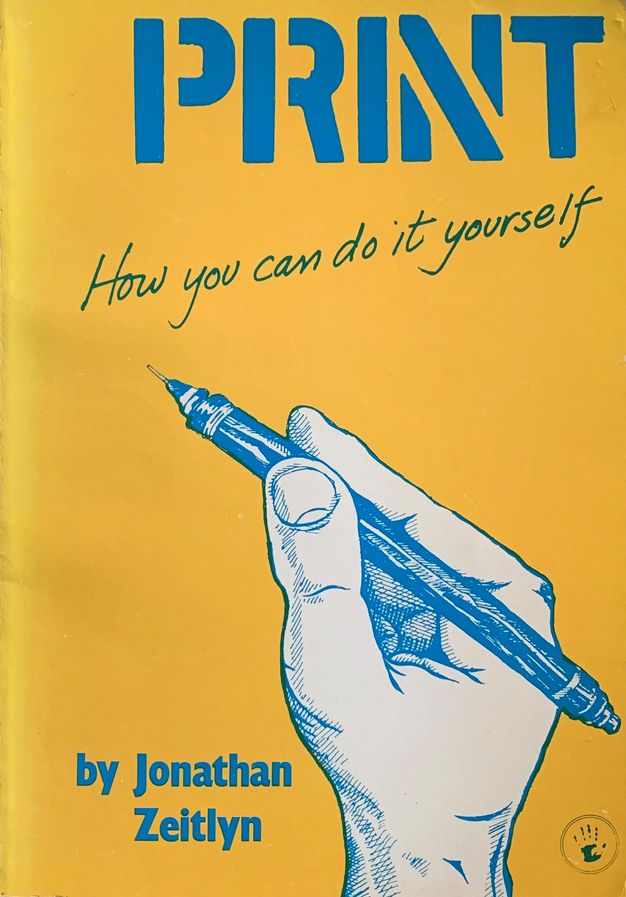

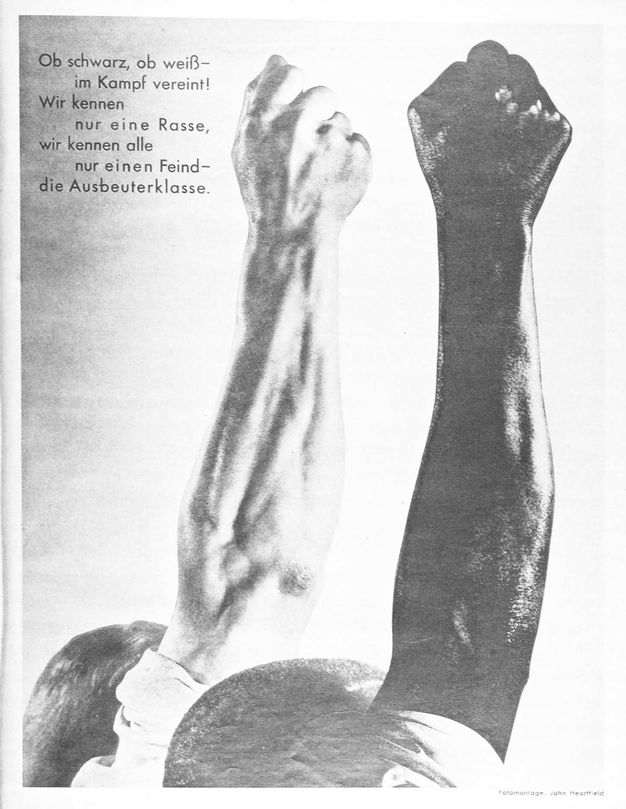

Considered alongside the front cover of Jonathan Zeitlyn’s instructional guide Print: How You Can Do It Yourself (fig. 29), the typography of the magazine’s masthead—hand-applied Letraset resembling stencilled lettering (itself a manual process)—clearly signifies the importance of the title having been self-published. Such logotypical logic evidently bolsters linguistic meaning,58 Camerawork’s title persuasively eliding equipment and labour to become process. But such formal characteristics can likewise engender meaning through the ways in which they encourage beholders themselves to enact labour, what Walter Benjamin in his classic account “The Author as Producer” termed apparatus, a means of “making co-workers out of readers or spectators”.59 For instance, Sabine Kriebel has argued, in an incredibly convincing reading of the magazine Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, that the periodical’s beholder, in grasping the top right-hand edge of the page on which a 1931 photomontage by John Heartfield is reproduced (fig. 30), “joins in their display of power and solidarity, and assimilates the real body with the territory of photographic illusion”.60 In the case of Camerawork, it is not so much what has been depicted than how the depictions have been (re)produced, as well as how their material realisation in the magazine requires a particular mode of physical interaction on the part of the beholder.

58

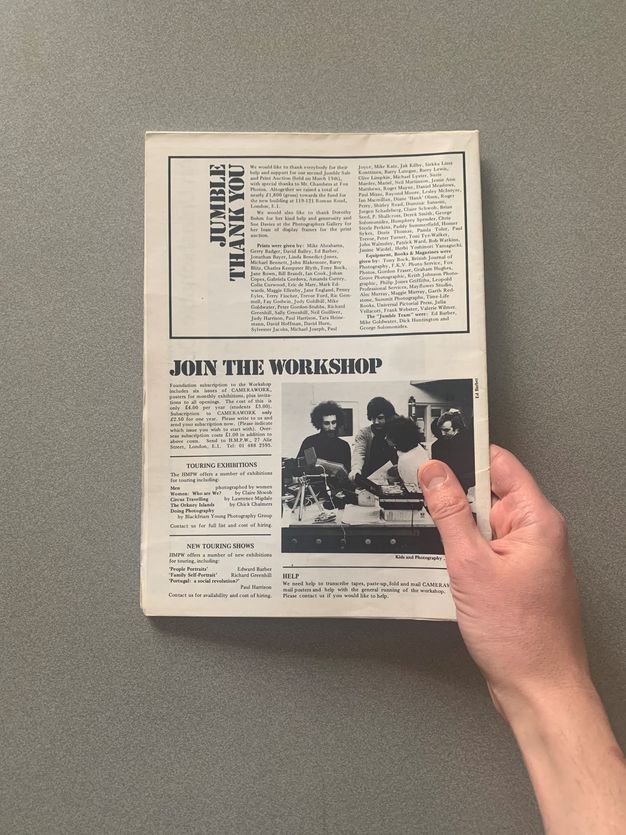

Artistic practices that enfold participation into their production of meaning have received not insignificant art-historical attention,61 not least a handful of magazines. “Fluxus periodicals, including décoll/age”, Anna-Maria Kanta has recently contended, “indicated the collectivization of cultural production through the private, and consequently dispersed performative act of reading”.62 Inherent in the unbound format of a magazine such as Aspen was “its participatory nature as a container of objects to be touched and grasped”,63 which Gwen Allen has argued challenged not only the framework of the museum as a space for viewing art but also the conventions of the medium of the magazine itself. What is more, a number of periodicals have sought ways to engender active involvement after the initial act of passive encounter.64 The title 0 to 9, for instance, edited by Bernadette Mayer and Vito Acconci, employs the strategy of visually and materially foregrounding the means of its own production. The cover of its first issue in 1967 featured an uncut mimeograph stencil consisting of indigo wax-coated paper, a trace of the very printing process by which it had itself been made (fig. 31). Readers were afforded the option of removing the page and typing their own work on it to be returned to the editors for later publication, thus becoming potential future contributors. “While the possibility remained largely symbolic (according to Acconci, nobody actually used the cover in this way)”, Allen has argued, “it expressed a reciprocity that was central to the kind of participatory community 0 to 9 strove to create among its readers”.65 Similarly, the catalogue for Kynaston McShine’s 1970 exhibition Information included “blank pages for the reader”: “please provide”, the curator asked, “your own text or images” (fig. 32).66 “If readers/viewers chose to take up this invitation”, Samantha Ismail-Epps has proposed, their action would transform a mass-produced publication into a highly personal edition". Again, however, such participation remains optional and such a reading conditional.67 A folded loose sheet inside the Winter 1977/1978 issue of the left-wing magazine Artery encouraged its beholders to “investigate the possibility of forming an ARTERY Readers Team (ART). This will not only provide you with the means to expand ARTERY sales but will put you in touch with possible contributors to ARTERY” (fig. 33).68 The material affordances of Camerawork, by contrast, actively and automatically enveloped its beholders into the magazine’s community through the unavoidable act of the manipulation of its pages. The necessary action of holding the magazine, followed by unfolding its pages, implicates the reader in the material politics of its production. The mode of its interpretation is thus inherent in the material conditions of the object, and meaning is produced through the physical engagement of the beholder, who by doing so joins the ranks of the collective who originally assembled the magazine, a Benjaminian apparatus intent on making its audience co-workers.69 As the beholder reaches the magazine’s back page (fig. 34), the textual invitations to participate—“Join the Workshop”; “We need help to … paste-up, fold and mail CAMERAWORK”—merely reinforce previously physically encountered material cues. Letters pages, of course, so often provide an important space for readers to participate in the ongoing work of a periodical, and Camerawork is no exception, publishing correspondence from as early as its second issue.70 And yet, by choosing to focus on them, most previous studies addressing reader engagement ultimately privilege the textual at the expense of the visual and material, eschewing formal affordances physically at hand before the written content has even been consumed.71 Through looking at the mechanics of Camerawork’s pages the participatory politics of the collective are first revealed.

61

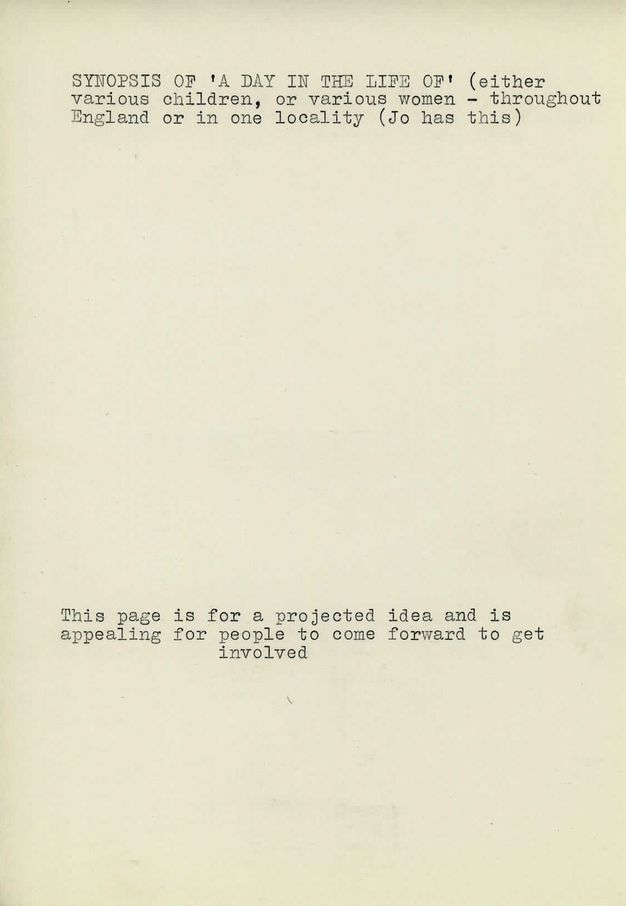

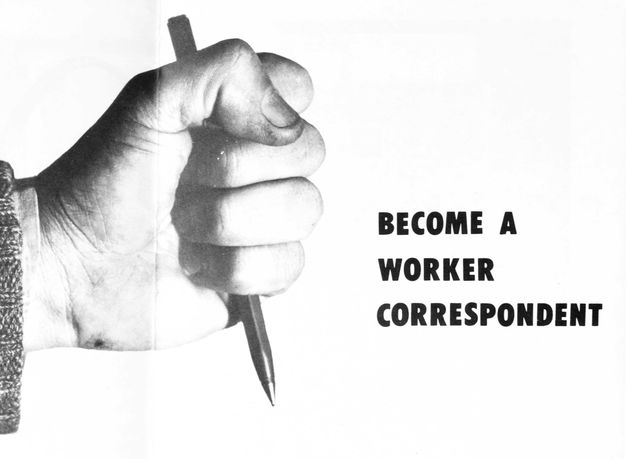

Spineless, unbound, loose-leaf formats have the potential to trouble ideas of the fixed and the finished;72 they facilitate multiple potential readings of a work. Inherent in them is the notion of the beholder as participant. One original interpretation may be (physically) implied, belying perhaps some form of authorial meaning or editorial intention, but that remains simply a starting point and only one starting point at that. In the case of Camerawork, the nature of the folds ensures that the linearity, the sequentiality, of the magazine is broadly retained.73 Instead, the efficacy and potency reside in physical manipulation, in unfolding the folded, an operation that is almost reactive or responsive, which as a result enfolds the beholder within the politics of the collective labour that produced the magazine and continues to do so. Its materiality becomes the apparatus by which the magazine’s readers “Join the Workshop”. Outlining the stakes of community photography in her essay “The Politics of Photography” for the first issue of Camerawork in February 1976, Jo Spence explained that “the most recent break with traditional fields of photography has been the use of photography as a TOOL by community activists”.74 The word TOOL, with its connotations of the hand-held, is emphatically typeset here in full capital letters, and more than likely harks back to an earlier publication, in fact a direct precursor to Camerawork.75 In 1975, prior to their amalgamation with Half Moon, Spence and Terry Dennett had produced three issues of Photography Workshop Newsletter, a very simple, unillustrated affair, merely typewritten and duplicated; the first issue was subtitled “Photography as a Tool”. Spence’s annotated draft of this issue, now in her archive at Ryerson University in Toronto, is revealing in terms of the newsletter’s successor Camerawork. Among the proposed content, for instance, is the note: “This page is for a projected idea and is appealing for people to come forward to get involved” (fig. 35).76 I cannot help but read “a projected idea” not just in terms of its prospective meaning but also in its physical sense, as if to indicate moving out from, and beyond, the flat and static page, almost gesturing to the manner of dynamic materiality with which I have been arguing Camerawork was imbued, bolstered by its unequivocal intention of garnering participation. Such an approach, as Spence made clear in her essay for the inaugural issue of Camerawork, “puts photography into the hands of lots of people”,77 a suggestion, I argue, that holds equally for community-produced publications about photography as for photography itself. Such strategies of manual participation go on to be rendered explicit in the pages of the broadsheet The Worker Photographer, put together in 1978 by Spence and Dennett immediately after their departure from the collective responsible for Camerawork.78 The invocation to “Become a Worker Correspondent” adorning the back page of issue 3 foregrounds the Benjaminian politics of participation in no uncertain terms (fig. 36).79 As the photographic cut-out of a left hand clenched around a pen makes clear, the emphasis is on the writer rather than the reader, as if the image advocates for the production of a mode of discourse about photography through attention to labour that is specifically manual. To write Camerawork’s history requires us to attend to the same tenets; its mediality is, above all, contingent on its materiality as a beheld and manipulable multiply-reproduced object. It should by now have become apparent that exactly how the contemporary scholar engages with this particular periodical as a historical artefact could not (literally) matter more. Be it on Instagram, with its manual actions of moving up and down and swiping left and right (fig. 37), or through “immersive 3D digital twins” (fig. 38), the frankly dystopian corporate description of a product ironically called Matterport that is used to facilitate virtual access to a subsequent iteration of Radical Visions at Pickford’s House (a museum in Derby), the labour that different remediations of Camerawork require the reader to perform engenders meaning that cannot be overlooked.

72

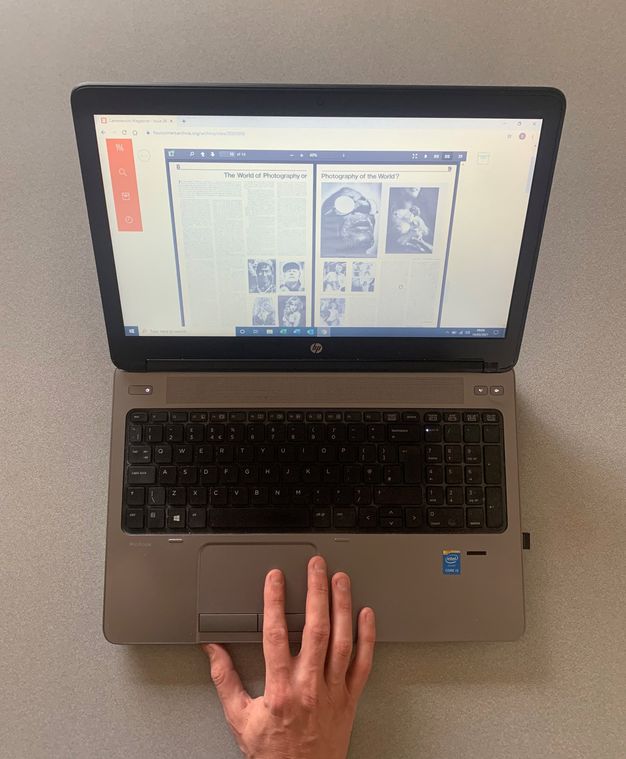

The COVID-19 pandemic has doubtless brought about changes to how scholars have had—and may continue—to work and to access archives. The Four Corners website (fig. 39), which makes the entire run of Camerawork available to the reader as free PDFs, has been an indispensable resource in the writing of this article.80 At the click of a mouse button it provides an instant encounter with just the type of facsimiles for which Parker and Pollock advocated all those years back. Indeed, as long ago as 2006, Sean Latham and Robert Scholes recognised in their landmark essay “The Rise of Periodical Studies” that new media technologies had “begun to transform the way that we view, handle, and gain access to these objects”.81 But the digitisation of magazines such as Camerawork gives rise to an uneasy (though perhaps unavoidable) tension: it enables (or eases) the labour of the present-day researcher, while simultaneously denying them the opportunity of (or at least discouraging them from) enacting the labour of the beholder that was so central to the meaning of the analogue version.82 The PDF as a technology is not, of course, without its limitations or ideological underpinnings, just like the other commercial products used to present earlier versions of this article, PowerPoint and Blackboard Collaborate. The portable document format in the case of Camerawork is in fact anything but portable. One can scroll pages up and down and from side to side, zoom in on and out from them, but not turn them over or actually touch them (fig. 40); perhaps the closest one can get to manual interaction is via the avatar of a hand, Adobe’s disembodied white cartoon cursor feature.83 The 2019 edition of Oxford University Press’s Dictionary of the Internet defines the PDF as “a file format which retains the visual integrity of the document”, while their Dictionary of Publishing from the same year categorises it as something that “integrates all the information required to display … a document”, assertions that do not completely fit the bill in this case.84 What is more, as a recent issue of the Journal of Modern Periodical Studies entitled “Digital Archives, Avant-Garde Periodicals” reminds us, the PDF as analogue surrogate is not all that needs to be grappled with here. The digital interfaces through which researchers peer at periodicals are themselves designed and designable products, structured by various patterns of labour. The Four Corners platform and content management system were developed for them by the creative digital and print agency on-IDLE. Characteristically, the site’s additional functionality concentrates on linguistic parameters, for instance, searching aided by optical character recognition and keyword tagging. Such digital endeavours, to be sure, have huge potential to bring magazines such as Camerawork to much wider audiences.85 But at what cost? “One of the paradoxes of digitizing avant-garde materials”, Drucker observes, “is that they have to be subject to processes of standardization in the precise bureaucratic and administrative terms against which they were originally conceived. The embodiment of protest against standardization is often fully evident in the physical formats of works where design decisions include deliberate deviation from norms”, the loose quires of Camerawork, say.86

80What should also be considered, in addition to reflecting on the ways in which digital technologies can have an impact on how one carries out research on the conditions of periodical publishing as a historical subject,87 is their related effect on the subsequent distribution and consumption of that same research—in other words, the contemporary frameworks for periodical production, including those that have brought the present article before your eyes. For instance, some might find it curious (or even compromising) that, having argued that scanned copies of Camerawork potentially rob beholders of a reading experience contingent on their physical interaction with the material reality of the magazine, I decided to submit this article to a born-digital journal for publication. This would, however, miss the point that both analogue and digital solutions come with their drawbacks (as well as benefits). We should strive to recognise and to reflect critically on the meaning and complexity of publishing ecosystems and their historical specificity. “The digital realm”, the editors of British Art Studies wrote in its inaugural issue in 2015, “offers new ways of looking at and engaging with images, the possibilities and pitfalls of which are being extensively debated”.88 In my own contribution to this discussion, I have shown, among other things, that it can also allow old ways of doing so to re-emerge. “The running of HMPW”, the collective explained in the first issue of Camerawork, “will reflect our central concern in photography which is not, ‘Is it art?’ but, ‘Who is it for?’”89 Similarly calling into question modes of participation in relation to periodical studies, be they material, social and political, or economic, the varied means of looking at Camerawork remind us that who engages with scholarship today, and how and where—issues that fuel the open access movement—gain from an approach to publishing underpinned by a historiographical awareness that is sensitive to both the visual and the material.

87The different ways of seeing this magazine should remind us that the mechanics of art historiography require getting one’s hands proverbially dirty. For our own interpretive labour too is today inextricable from that of the collective who came together from the middle of the 1970s to produce Camerawork. Tempting as the lure of modernity may be, with its promises of champagne, chic, and music, the labour of periodical studies, as I have shown, demands a more hands-on approach. Mirroring the Half Moon Photography Workshop’s manifesto, I have sought to demystify the processes—visual, material, historiographical—by which ideas, views, and information about Camerawork are exchanged, for I too “see this as part of our struggle to learn, to describe, to share experiences”.90 Equally, I urge present-day editorial practitioners, those who facilitate the production, distribution, and consumption of such work, to recall the words of Alfred Stieglitz, “that reproductions of photographic work must be made with exceptional care and discretion if the spirit of the originals is to be retained”.91

90Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the conference “Visual Culture Methodologies for Periodical Studies” at Northumbria University in March 2021, and at the Forschergruppe Journalliteratur conference “Periodicals as/in Media Constellations” at the University of Cologne in November 2021. It has also benefitted from the generous input and encouragement of Johanna Gosse, Catherine Grant, Jennifer Greenhill, Victoria Horne, Alfie Johnson, and Megan Luke.

About the author

-

Samuel Bibby is managing editor of Art History. He holds a PhD from the University of Sussex and is currently completing a book project entitled “Art History Works in Print: Producing Periodicals in 1970s Britain”, which looks at art magazines and art-historical journals including Studio International and The Connoisseur; Art-Language and Artscribe; the Oxford Art Journal and Apollo; Art Monthly; Art History and The Burlington Magazine; and BLOCK. Parts of it have already appeared in both print (Art History) and digital journals (British Art Studies). This article is part of a new project that looks at periodicals and different forms of participation from the 1960s to 1980s, including Signals Newsbulletin, Camerawork, Black Phoenix, Feminist Arts News, and Ten8.

Footnotes

-

1

Yve-Alain Bois, “El Lissitzky: Reading Lessons”, trans. Christian Hubert, October 11 (Winter 1979): 118. ↩︎

-

2

Alan Marshall, Changing the Word: The Printing Industry in Transition (London: Comedia, 1983), 41. ↩︎

-

3

For an excellent recent summary and analysis of many of the challenges facing this field today, see Maria DiCenzo, “Remediating the Past: Doing ‘Periodical Studies’ in the Digital Era”, English Studies in Canada 41, no. 1 (March 2015): 19–39. See also Patrick Collier, “What Is Modern Periodical Studies?”, Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 6, no. 2 (2015): 92–111. ↩︎

-

4

Eric Bulson, “The Little Magazine, Remediated”, Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 209–12. ↩︎

-

5

Laurel Brake, “Tacking: Nineteenth-Century Print Culture and its Readers”, Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net 55 (August 2009): 41, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ravon. See also Linda K. Hughes, “Sideways! Navigating the Material(ity) of Print Culture”, Victorian Periodicals Review 47, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 1–30; and James Mussell, “Beyond the ‘Great Index’: Digital Resources and Actual Copies”, in Journalism and the Periodical Press in Nineteenth-Century Britain, ed. Joanna Shattock (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 17–30. Beyond this nineteenth-century focus see, for example, Craig Farrell, “The Poetics of Page-Turning: The Interactive Surfaces of Early Modern Printed Poetry”, Journal of the Northern Renaissance 8 (Spring 2017): 1–33. ↩︎

-

6

The exhibition The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines, jointly organised by the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Art Libraries Society in 1976, is a case in point. For an in-depth consideration of this, together with the various ways in which it was translated into print, see Samuel Bibby, “‘The Assemblage of Specimens’: The Magazine as Catalogue in 1970s Britain”, British Art Studies 14 (November 2019), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-14/sbibby. See also Samuel Bibby, “Xerox Symphony”, CAA Reviews, http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/4217. ↩︎

-

7

An analogy might be drawn here with sculpture, and in particular its relationship to photography, a topic that has generated not insignificant scholarly attention: see, for example, Geraldine A. Johnson, ed., Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Patrizia Di Bello, Sculptural Photographs: From the Calotype to Digital Technologies (London: Bloomsbury, 2017); and Sarah Hamill and Megan R. Luke, eds., Photography and Sculpture: The Art Object in Reproduction (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2017). ↩︎

-

8

For a recent historical account see, for example, Mathilde Bertrand, “The Half Moon Photography Workshop and Camerawork: Catalysts in the British Photographic Landscape (1972–1985)”, Photography and Culture 11, no. 3 (November 2018): 239–59. Earlier treatments include Kathy Myers, “Camerawork”, in Photographic Practices: Towards a Different Image, ed. Stevie Bezencenet and Philip Corrigan (London: Comedia, 1986), 85–94. For the wider context of community printshops, see Carol Kenna, Lyn Medcalf, and Rick Walker, eds., Printing Is Easy…? Community Printshops, 1970–1986 (London: Greenwich Mural Workshop, 1986); and Jessica Baines, “Democratising Print? The Field and Practices of Radical and Community Printshops in Britain, 1968–98” (PhD dissertation, London School of Economics, 2016). ↩︎

-

9

Half Moon Photography Workshop, “Statement of Aims”, Camerawork 1 (February 1976): 8. ↩︎

-

10

See Exit Photography Group, Down Wapping (London: East End Docklands Action Group, 1974). ↩︎

-

11

For Dan Graham’s Poem Schema see, for example, Alexander Alberro, “Structure as Content: Dan Graham’s Schema (March 1966) and the Emergence of Conceptual Art”, in Dan Graham, ed. Gloria Moure (Barcelona: Fundació Tapies, 1998), 21–30. ↩︎

-

12

Paul Trevor, “The Price of Self Expression: An Article on Self-Publishing”, Camerawork 1 (February 1976): 7. ↩︎

-

13

Ed Barber, “Reviewing the Situation”, Camerawork 7 (July 1977): 9. For a good example of the kind of approach Barber advocated, see John Tagg’s review of John Sanders, ed., Photography Year Book (London: Fountain Press, 1977), “The World of Photography or Photography of the World?”, Camerawork 6 (April 1977): 8–9. ↩︎

-

14

Excellent recent accounts of documentary photography in which its reproduced content plays a part include Jorge Ribalta, ed., Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2015), 30–35; and Steve Edwards, “‘Dirty Realism’: Documentary Photography in 1970s Britain—A Maquette”, in Art as Worldmaking: Critical Essays on Realism and Naturalism, ed. Malcolm Baker and Andrew Hemingway (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 248–67. ↩︎

-

15

See Samuel Bibby, “‘The Pursuit of Understanding’: Art History and the Periodical Landscape of 1970s Britain”, Art History 40, no. 4 (September 2017): 808–37. ↩︎

-

16

Harold Frayman, David Griffiths, and Chris Chippindale, Into Print: A Guide to Publishing Non-Commercial Newspapers and Magazines (London: Teach Yourself Books, 1975), 242. For an example of such a strategy appearing in the pages of Camerawork itself, see Bob Long, “Camerawork 8 and the Political Photographer”, Camerawork 16 (November 1979): 10, in which he briefly considers it in relation to titles from the amateur press such as Photo Technique and Amateur Photographer, professional magazines such as the British Journal of Photography, and what he terms the “modernist photo magazine”, Creative Camera. ↩︎

-

17

See Barbara Taylor, “History Workshop Journal”, 2008, Making History: The Changing Face of the Profession in Britain (London: Institute of Historical Research, 2008), https://archives.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/articles/HWJ.html. ↩︎

-

18

See Crispin Aubrey, Charles Landry, and Dave Morley, Here Is the Other News: Challenges to the Local Commercial Press (London: Minority Press Group, 1980), 54–60. ↩︎

-

19

For Arbeiterfotografie, see Sarah E. James, Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures across the Iron Curtain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013); and Ribalta (ed.), Not Yet, 25–30. For Picture Post, see Stuart Hall, “The Social Eye of Picture Post”, Working Papers in Cultural Studies 2 (1972): 71–120. And for Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung see, for example, Andrés Mario Zervigón, John Heartfield and the Agitated Image: Photography, Persuasion and the Rise of Avant-Garde Photomontage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

20

For Creative Camera, see David Brittain, ed., Creative Camera: Thirty Years of Writing (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999). For Album, see Bill Jay, “Album: A Memoir”, History of Photography 17, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 1–9. ↩︎

-

21

The literature on this periodical is vast; in the first instance, see Jonathan Green, ed., Camera Work: A Critical Anthology (New York: Aperture, 1973), 9–23. ↩︎

-

22

Alfred Stieglitz et al., “An Apology”, Camera Work 1 (January 1903): 15. A parallel may be drawn here with a passage from Walter Benjamin’s classic account of translation: “If the kinship of languages is to be demonstrated by translations, how else can this be done but by conveying the form and meaning of the original as accurately as possible?” (Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator” (1923), trans. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968), 72). ↩︎

-

23

For Tom Picton’s role, see Frances Whorrall-Campbell, “Behind the Lens: Mike Goldwater”, 10 July 2019, https://fourcornersarchive.org/news-and-events/behind-the-lens-mike-goldwater. For Afterimage, see Grant H. Kester, ed., Art, Activism, and Oppositionality: Essays from Afterimage (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), as well as Alex J. Sweetman, “‘Everything Overlaps: There Are No Edges’”, Afterimage 1, no. 1 (March 1972): 2–3; Charles M. Hagen, “Editorial: A Position of Service”, Afterimage 1, no. 1 (March 1972): 4; and “Visual Studies Workshop: Report to Members”, Afterimage 3, no. 3 (September 1975): 10–13. For loose quires, see Thomas Landau, ed., Encyclopaedia of Librarianship, 2nd ed. (London: Bowes & Bowes, 1961), vol. 1, 173. For French folds, see Clifford Burke, Printing It: A Guide to Graphic Techniques for the Impecunious (New York: Ballantine Books, 1972), 94. ↩︎

-

24

For a thoughtful reflection upon the various implications of making such reproductions oneself, see Daniel Wakelin, “A New Age of Photography: ‘DIY Digitization’ in Manuscript Studies”, Anglia 139, no. 1 (April 2021): 71-93. Also of note, and in particular in relation to the question of objects that cannot necessarily be seen (and captured) all at once, is Kathryn Rudy, “Video Killed the Photo Star: Digital Photography and the Challenges of Folded and Rolled Manuscripts”, https://youtu.be/LyoNARyvFZA. ↩︎

-

25

See also Peter Schweppe, “The Politics of Removal: Kursbuch and the West German Protest Movement”, The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics and Culture 7, no. 2 (2014): 138–154, in which he argues that the study of such removable material “can reinforce concepts of how politics tends to get reproduced in the design and circulation of periodicals” (p. 147). ↩︎

-

26

For more on the “cut out and keep” format, see Tom Gretton, “Signs for Labour-Value in Printed Pictures after the Photomechanical Revolution: Mainstream Changes and Extreme Cases around 1900”, Oxford Art Journal 28, no. 3 (October 2005): 383. ↩︎

-

27

See Allan Charles Madden, “The Gallerist as Publisher: A Critical History from 1900 to the Present” (PhD dissertation, University of Edinburgh, 2018), in particular chapter 3, which addresses Derrière le miroir. ↩︎

-

28

For a recent and thorough treatment of this topic, see Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

29

See Susannah Thompson, “The Artist as Critic: Art Writing in Scotland, 1960–1990” (PhD dissertation, University of Glasgow, 2010), 92–103. ↩︎

-

30

A recent account has argued for the book as a technology to be seen as “a set of instructions about how [it] should be handled and read” (Leah Price, What We Talk about When We Talk about Books: The History and Future of Reading (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 31). The magazine Mécano from earlier in the twentieth century provides an example of a periodical designed with the mechanics of its handling at the forefront of its meaning (see Michael White, “Playing with Mécano—A Zero-Sum Game?”, in The Great Monster Dada Show, ed. Ana María Bresciani and Oda Wildhagen Gjessing (Høvikodden: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, 2019), 66–79). ↩︎

-

31

The tendencies I outline here seem to have been in place from the fore. Consider, for instance, “HMPW Launch Alternative Photography Magazine”, Visual Education: A Journal on All Aspects of Education Technology 27 (April 1976): 4, which appears to have been the first review of the magazine and which includes no mention whatsoever of its visual or material nature. The only exception that I have come across is a single sentence: “CAMERAWORK is laid out with love and beautifully printed” (Mike Wells, letter in “Letters”, Camerawork 5 (February 1977): 5). By 1983, however, the high production values of Camerawork had been recognised in some quarters (see Chris Treweek and Jonathan Zeitlyn, The Alternative Printing Handbook (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), 62). ↩︎

-

32

Nothing illustrates this better than the often-reproduced essay from its first issue: Jo Spence, “The Politics of Photography”, Camerawork 1 (February 1976): 1. See, for instance, the following iterations in British Journal of Photography 123, no. 6035 (26 March 1976): 254–55; in Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present, ed. Liz Heron and Val Williams (London: I.B. Tauris, 1996), 174–78; in Jo Spence, Cultural Sniping: The Art of Transgression (London: Routledge, 2007), 31–36; and Ribalta (ed.), Not Yet, 114–15. On the topic of the anthology and its relationship to the erasure of meaning, see George Bornstein, “How to Read a Page: Modernism and Material Textuality”, in Material Modernism: The Politics of the Page (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 5–31. See also James O’Sullivan, “The New Apparatus of Influence: Material Modernism in the Digital Age”, International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 8, no. 2 (October 2014): 226–38. ↩︎

-

33

Evans’s treatment of the magazine’s appearance and production, it should be stressed, is cursory (Jessica Evans, ed., Camerawork Essays: Context and Meaning in Photography (London: Rivers Oram Press, 1997), 11–35). The same can be said of Myers, “Camerawork”. ↩︎

-

34

Peter Marshall, “The Repackaging of 1970s British Photography”, Visual Anthropology Review 14, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1998): 86. Recent testimony from Goldwater suggests that “the only sheet of Letraset we had left that had all the letters in the right font size was Stencil Bold, so that became our logo” (see Whorrall-Campbell, “Behind the Lens”). Meanwhile, a recent account has similarly emphasised that the left-wing ethos of Camerawork was “evident in the magazine’s design, which utilised industrial typography, uncompromising black and white images and a colloquial fold-out structure” (see Geoffrey Batchen, “Distinctly Discursive: Photo-Magazine Culture”, in The 80s: Photographing Britain, ed. Yasufumi Nakamori, Helen Little and Jasmine Chohan (London: Tate Publishing, 2024), 19). ↩︎

-

35

Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, eds., Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement, 1970–85 (London: Pandora, 1987), xvi. On this topic more recently, see Samuel Bibby, “Hidden Trails in Art History”, Art History 40, no. 1 (February 2017): 204–9. Over the years a handful of art magazines have been reproduced in facsimile, specifically replicating the bound (and folded) form of their respective individual issues, including Signals Newsbulletin, reproduced by Iniva in 1995, and more recently bauhaus, reproduced by Lars Müller in 2019. For a seminal essay on the topic of facsimile editions more broadly, see Michael Camille, “The Très Riches Heures: An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Critical Inquiry 17, no. 1 (Autumn 1990): 72–107. And, more generally, see also Bonnie Mak, How the Page Matters (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 66. ↩︎

-

36

At no point in her study does Stacey discuss specific details of the magazine’s production. The closest to such a focus remains her briefest mention of the effect of “the accessibility and affordability of new technologies, including printing processes” (see Noni Stacey, Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), 23–24). ↩︎

-

37

Jo Spence, “Golden Rules OK?”, Camerawork 3 (July 1976): 5. Stacey captions it as “Miners discuss union issues, Kellingley Colliery, Yorkshire”. ↩︎

-

38

See Stacey, Photography of Protest and Community, 49. The image reproduced here appears to be of an original photographic print rather than its subsequent iteration as a magazine page. ↩︎

-

39

See “Pages from a Magazine: CAMERAWORK”, 2011, White Columns, https://whitecolumns.org/exhibitions/pages-from-a-magazine-camerawork. ↩︎

-

40

An exhibition on the magazine Studio International in 2015 included in addition to copies in vitrines a film (made by Oliver Beatty) in which the curator could be seen turning its pages whilst providing commentary. The accompanying catalogue, itself modelled on the magazine’s format, intriguingly described itself as a “rematerialised version” of the originals; see Jo Melvin, Five Issues of Studio International (London: Raven Row, 2015), 2. Similarly, the 2025 exhibition Breaking Lines: Futurism and the Origins of Experimental Poetry at the Estorick Collection in London included several video displays showing the pages of publications being turned by hand. ↩︎

-

41

See Victor Burgin, “Art, Common Sense and Photography”, Camerawork 3 (July 1976): 1–2; and Ed Barber, “Doing-It-Yourself: Touring Exhibitions”, Camerawork 10 (July 1978): 8–9. The Half Moon Photography Workshop produced numerous touring exhibitions themselves, usually consisting of photographic material on laminated panels, almost like a collection of unbound pages arranged for display. ↩︎

-

42

For more on this, see Bibby, “‘The Assemblage of Specimens’”. ↩︎

-

43

I consider this exhibition catalogue to be a landmark publication in terms of its approaches to the reproduction of printed material. In particular, see Martina Droth and Paul Messier, “Sculpture, Photography, and the Printed Page”, in Bill Brandt, Henry Moore, ed. Martina Droth and Paul Messier (New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art, 2020), 9; and Paul Messier and Martina Droth, “Photography in Four Dimensions”, in Droth and Messier, Bill Brandt, Henry Moore, 11–13. For Yale University Press’s promotional video, see https://youtu.be/t0tKndTThOo. The catalogue of a 2006 exhibition is also of note for the variety of ways in which it reproduces on its pages the pages of the objects that were on display (see Beatriz Colomina and Craig Buckley, eds., Clip, Stamp, Fold: The Radical Architecture of Little Magazines, 196X to 197X (Barcelona: Actar, 2010)). Its publisher promoted the printed volume by creating a 44-page preview using Issuu, the online platform “which turns PDFs and other file types into digital flipbooks and shareable content types” (see https://issuu.com/actar/docs/clipstampfold). ↩︎

-

44

Carla Mitchell, “Half Moon Photography Workshop & Camerawork”, in Radical Visions: The Early History of Four Corners and Camerawork, 1972–1987 (London: Four Corners, 2018), 6. ↩︎

-

45

Such a move conforms to the historiographical trope whereby “representational practices encoded in works of art continue to be encoded in their commentaries” (Michael Ann Holly, Past Looking: Historical Imagination and the Rhetoric of the Image (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 79). ↩︎

-

46

For the relationship between fingers and eyes within the context of magazine consumption, see Jennifer A. Greenhill, “Flip, Linger, Glide: Coles Phillips and the Movement of Magazine Pictures”, Art History 40, no. 3 (June 2017): 582–611. ↩︎

-

47

Mitchell, “Half Moon Photography Workshop & Camerawork”, 8. ↩︎

-

48

For a recent treatment of folds, see Inscription: The Journal of Material Text—Theory, Practice, History 3 (2022), https://inscriptionjournal.com/issue-3-folds. ↩︎

-

49

The Radical Visions catalogue was produced in six different versions, each cover bearing a different photographic image, all portraits of the founder members of Half Moon Photography Workshop and Four Corners. ↩︎

-

50

See Four Corners Archive, https://fourcornersarchive.org. ↩︎

-

51

Half Moon Photography Workshop, “Statement of Aims”, 8. ↩︎

-

52

Kevin McDonnell, “Left Press: Exclusive Wedge In-Depth Analysis”, Wedge 3 (Autumn 1978): 24. For a similar (and in this instance unbound) guide, see Chris Chippindale, Michael Norton, and Jonathan Zeitlyn, The Community Newspaper Kit (London: Directory of Social Change, 1980). ↩︎

-

53

Burke, Printing It, 91. ↩︎

-

54

See N. Katherine Hayles, “Print Is Flat, Code Is Deep: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis”, Poetics Today 25, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 72. ↩︎

-

55

Johanna Drucker, “Performative Materiality and Theoretical Approaches to Interface”, Digital Humanities Quarterly 7, no. 1 (2013): 4. ↩︎

-

56

Drucker, “Performative Materiality and Theoretical Approaches to Interface”, 8. ↩︎

-

57

Johanna Drucker, “Self-Reflexivity in Book Form”, in The Century of Artists’ Books (New York: Granary Books, 1995), 161. ↩︎

-

58

I borrow this concept from Kristin Romberg, Gan’s Constructivism: Aesthetic Theory for an Embedded Modernism (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 150. ↩︎

-

59

Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer” (1934), trans. John Heckman, New Left Review 62 (July/August 1970): 93. ↩︎

-

60

Sabine T. Kriebel, Revolutionary Beauty: The Radical Photomontages of John Heartfield (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 100. ↩︎

-

61

See, for example, Frank Popper, Art: Action and Participation (London: Studio Vista, 1975); and, more recently, Claire Bishop, ed., Documents of Contemporary Art: Participation (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2006), and Anna Dezeuze, ed., The “Do-It-Yourself” Artwork: Participation from Fluxus to New Media (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

62

Anna-Maria Kanta, “Décoll/age: Bulletin aktueller Ideen: A Manual for Navigating the Interstitial Spaces between Surviving and Living”, Object 18 (2016): 55. ↩︎

-

63

Allen, Artists’ Magazines, 65–66. ↩︎

-

64

I also address this topic in Samuel Bibby, “The Magazine as Manifesto: Black Phoenix and the Reproduction of Racial Politics in 1970s Britain”, in Counter Print: The Alternative Art Press in Britain after 1970, ed. Victoria Horne (Manchester: Manchester University Press, forthcoming). ↩︎

-

65

Allen, Artists’ Magazines, 73. ↩︎

-

66

Kynaston L. McShine, Information (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970), 142–43. ↩︎

-

67

Samantha Ismail-Epps, “Artists’ Pages: The Accessibility of Art through the Printed Page, 1966–1973” (PhD dissertation, University of the Arts London / Norwich University of the Arts, 2018), vol. 1, 219–20. ↩︎

-

68

Artery 13 (Winter 1977/1978), loose sheet. ↩︎

-

69

Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners (1975) was similarly interpreted at the time (see Claire Johnston and Paul Willemen, “Brecht in Britain: The Independent Political Film (on The Nightcleaners)”, Screen 16, no. 4 (Winter 1975): 101–18). On this work more recently, see Siona Wilson, Art Labor, Sex Politics: Feminist Effects in 1970s British Art and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 1–51. ↩︎

-

70

See, for example, David Hoffman, “Letter”, Camerawork 2 (April/May 1976): 3. ↩︎

-

71

See, for instance, Allison Cavanagh and John Steel, eds., Letters to the Editor: Comparative and Historical Perspectives (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). ↩︎

-

72

Consider, for instance, Daniel Spoerri’s Material, Wallace Berman’s Semina, or William Copley’s SMS (see Allen, Artists’ Magazines, 277, 295, 297 respectively). ↩︎

-

73

On the relationship between a magazine’s linearity and reading patterns, see Sally Stein, “The Graphic Ordering of Desire: Modernization of a Middle-Class Women’s Magazine, 1914–1939”, Heresies 5, no. 2, issue 18 (1985): 7; and Tom Gretton, “Difference and Competition: The Imitation and Reproduction of Fine Art in Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Weekly News Magazines”, Oxford Art Journal 23, no. 2 (2000): 146. ↩︎

-

74

Spence, “The Politics of Photography”, Camerawork, 1. ↩︎

-

75

The word TOOL would also go on to be used in subsequent grassroots endeavours in print. The Greenham Factor, a 1984 pamphlet bearing remarkable physical similarities to the parameters of Camerawork (A2, folded, and incorporating a poster for display), included the following statement, for example: “This publication is itself a tool. Use the pages as posters, or send one to your local MP” (Greenham Common Peace Camp, The Greenham Factor (London: Greenham Print Prop, 1984, unpaginated)). ↩︎

-

76

Annotated draft of Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, Photography Workshop Newsletter 1 (1975), unpaginated (Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto). For this earlier collective endeavour, see “Photo Workshop in Islington”, in George Hughes, “Newsview”, Amateur Photographer 152, no. 13 (24 September 1975): 147. ↩︎

-

77

Spence, “The Politics of Photography”, Camerawork, 1. ↩︎

-

78

For just one account of this, see Terry Dennett and Jo Spence, “Photography Workshop 1974 Onwards”, in Jo Spence, Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography (London: Camden Press, 1986), 62–65. ↩︎

-

79

Worker Photographer 3 (1978): 4. This image is just one of the participatory cues in the magazine. This same issue, for example, was accompanied by a photocopied single A4 sheet containing explanation and instructions: “The double-paged poster in this issue is deliberately ‘unfinished’ so that readers can use it as the basis for their own local examination of the media. Just try adding or substituting some of your local news for the images used, add text and make it into your own political poster—perhaps even treat it as a wall newspaper (a subject we will be dealing with in a later issue). We want you to use this issue, not just read it. And we’d like to hear from you (perhaps sending us a copy of what you do) so that we can continue a dialogue”. For a recent account that considers the Worker Photographer within the context of Dennett’s radical practice, see Johanna Klinger, “Working Together: Creating Social Spaces—The Praxis of Terry Dennett”, in Camera Forward!, ed. MayDay Rooms Collective (London: MayDay Rooms, 2021), 65–100. ↩︎

-

80

Alongside the website for its archive, Four Corners also has an online shop, an “eBay for Charity” page where one can purchase “vintage issues of Camerawork magazine”, underscoring that, in concert with the freely available digitised versions, the material originals have now become collectable commodities (albeit relatively inexpensive ones); see https://charity.ebay.co.uk/charity/i/Four-Corners/163303, accessed 22 March 2024. Such a market might be considered a de facto archive, but one based on the availability of the least popular issues of the publication. The conversion of surplus value into economic capital, and the reification of Camerawork in terms of exchange value rather than as an object of use, are both surely not indicative of what the magazine was, or what it stood for, but also complicate the recognised tension between the distribution and circulation of digitally remediated versions and analogue originals. See Jasmine E. Burns, “Information as Capital: The Commodification of Archives and Library Labor”, Visual Resources Association Bulletin 45, no. 1 (2018): article 9. ↩︎

-

81

Sean Latham and Robert Scholes, “The Rise of Periodical Studies”, PMLA 121, no. 2 (March 2006): 518. ↩︎

-

82

A recent publication by Juliet Sperling has managed to counter this problem through the use of different supplementary technologies in print and online iterations to animate the material being addressed. The print version was accompanied by a tipped-in page that readers could cut out to recreate a facsimile version of the folded object on which she focused, while the online version included a video illustrating the mechanics of the same work (see Juliet Sperling, “Unfolding Metamorphosis, or the Early American Tactile Image”, American Art 35, no. 3 (Fall 2021): 58–87; and, for the video, https://journals.uchicago.edu/doi/suppl/10.1086/717650. ↩︎

-

83

For the PDF, see Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 111–35. ↩︎

-

84

Darrel Ince, ed., A Dictionary of the Internet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Adrian Bullock, Chris Jennings, and Nicola Timbrell, eds., A Dictionary of Publishing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), DOI:10.1093/acref/9780191863592.001.0001. ↩︎

-

85

For an analysis of the practices of digitising analogue collections and their consequences for historical research, see Charles Jeurgens, “The Scent of the Digital Archive: Dilemmas with Archive Digitisation”, Low Countries Historical Review 128, no. 4 (2013): 30–54. ↩︎

-

86