Gavin Stamp and the Tradition of the Activist-Scholar in Architectural History

Gavin Stamp and the Tradition of the Activist-Scholar in Architectural History

By Joshua Mardell

Abstract

This article positions the architectural historian Gavin Stamp (1948–2017) as an exemplar of one of architectural history’s underexplored traditions: the activist-scholar. It argues that Stamp’s wide-ranging career was a cumulative campaign against what he saw as architectural ignorance and philistinism, resulting in “uglification”. Consequently, the hallmark of his work was an emphasis on widening an appreciation of architecture, on bridging professional and public spheres and on strengthening the culture of critique. Contextualising Stamp’s contribution involves reuniting his scholarly work in print with his wider activities, evidence for which can be found in an informal and less accessible sphere of reminiscences, journalism, personal communication and ephemera. The article therefore makes recourse to oral history and to Stamp’s archive, gifted to the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art following his death. It examines Stamp’s inventive forms of advocacy, the networks within which he operated, how he mediated his causes across diverse platforms—and to what end. The article shows that, although as a student at Cambridge Stamp subscribed to an anti-modernist disposition as part of a right-leaning coterie, over his career his early certitudes were slowly shaken down and some of his more inveterate hostilities gradually softened.

Introduction

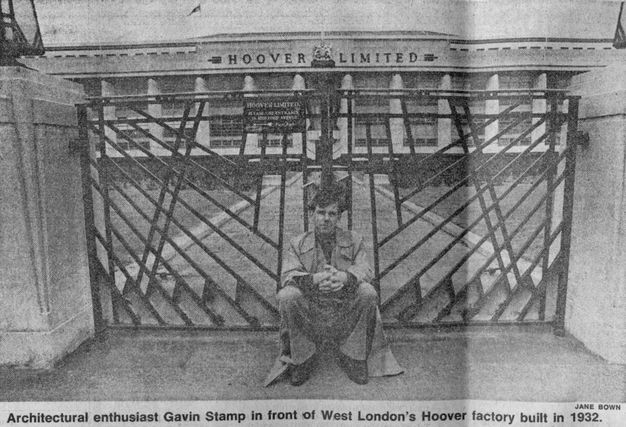

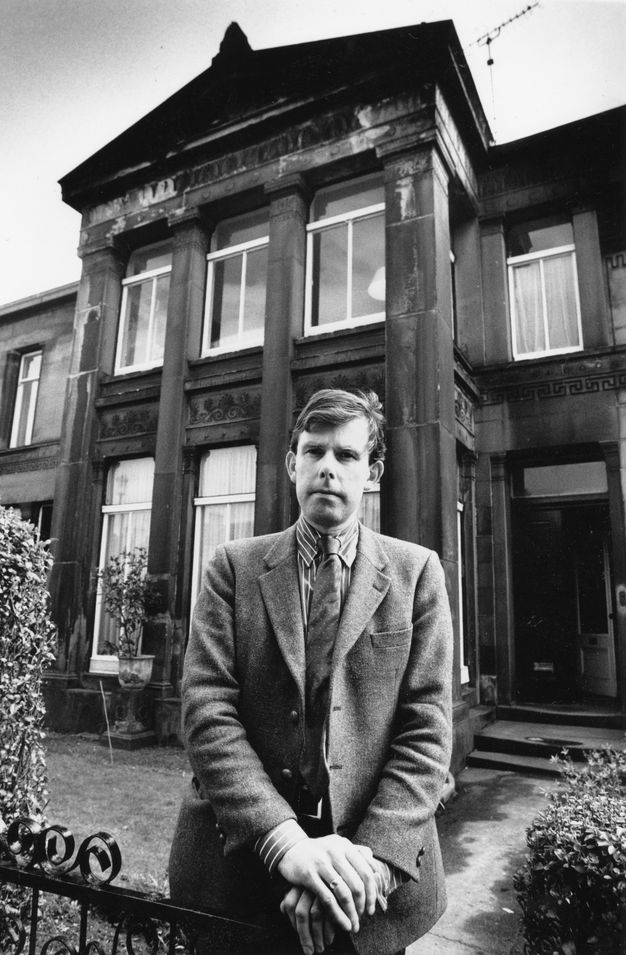

“I knew it was wrong at the time”, recalled the architectural historian Gavin Stamp (1948–2017) (fig. 1).1 He was remembering his family home on the edge of the green belt in Hayes, Kent, a detached 1930s neo-Tudor property with leaded light windows (fig. 2). It epitomised the “By-pass Variegated”, a term coined by one of Stamp’s heroes, Osbert Lancaster, “the essential taxonomist of neo-Tudor”.2 According to Stamp, his parents despoiled the home in the 1950s by replacing the space that occupied the living-room fireplace with a large plate-glass window stretching the width of the hipped roof, and removing the chimney. “They made what was quite a nice house into a complete sort of awful mongrel”.3 Such were the roots of Stamp’s lifelong, heartfelt rally against architectural philistinism and barbarism—“the ubiquitous enemy”.4

1

Suburbia would go on to fascinate Stamp, as it did his friend John Betjeman. This extended to neo-Tudor architecture.5 It yielded an important lesson against Betjeman’s “Antiquarian Prejudice”: “It is the task of the historian to cut through élitist and snobbish prejudices and regard buildings—all buildings—as significant cultural manifestations, however laughable or mediocre they may be”.6 In a career spanning half a century, Stamp consistently redirected our gaze away from orthodox views on architecture and its accepted canons. The Betjemanic theme of neglect proliferated. Indeed, Stamp’s project furthered Betjeman’s own: he set out to validate what he saw as the missing sections of architectural history albeit, as a product of his time, he limited his inquiries almost exclusively to the contributions of white European men. Stamp did, however, recognise the “intolerant misogyny endemic in the masculine world of architectural history”.7

5From a prosperous middle-class background, Gavin was born to Norah Stamp (née Rich) and Barry Stamp, who chaired the grocery business Cave Austin and Co. Gavin’s brother Gerard remembered his (later renowned) contrarian manner from his childhood, when he and his father “always played devil’s advocate with each other. Neither would give in”.8 Norah came from a lower middle-class Bristolian family, several of whom were Fabian socialists.9 Yet—unsurprisingly for someone so socially ambitious—two grander relatives inspired Gavin: his father’s uncles, the geographer Sir Dudley Stamp (1898–1966) and Josiah Stamp, 1st Baron Stamp (1880–1941), who had been a director of the Bank of England and chairman of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. Being the progeny of socialists and self-made gentry helped to form a future architectural historian who was to present himself as an effete member of the upper class and to admire grand heritage, yet insist on inclusivity, and to become a leading exemplar of a form of socially engaged intellectual endeavour within architectural history.

8Following his untimely death from cancer in December 2017, Stamp’s archive was gifted by his widow, Rosemary Hill, to the Paul Mellon Centre (PMC) for Studies in British Art. This acquisition has enabled me to revisit the texture and nuance of his life and, with the addition of anecdotal evidence, to tell Stamp’s story more fully than has hitherto been possible.10 The archive reveals the pluralistic thematic territories that occupied him over a career traversing the historiographical terrains vague.

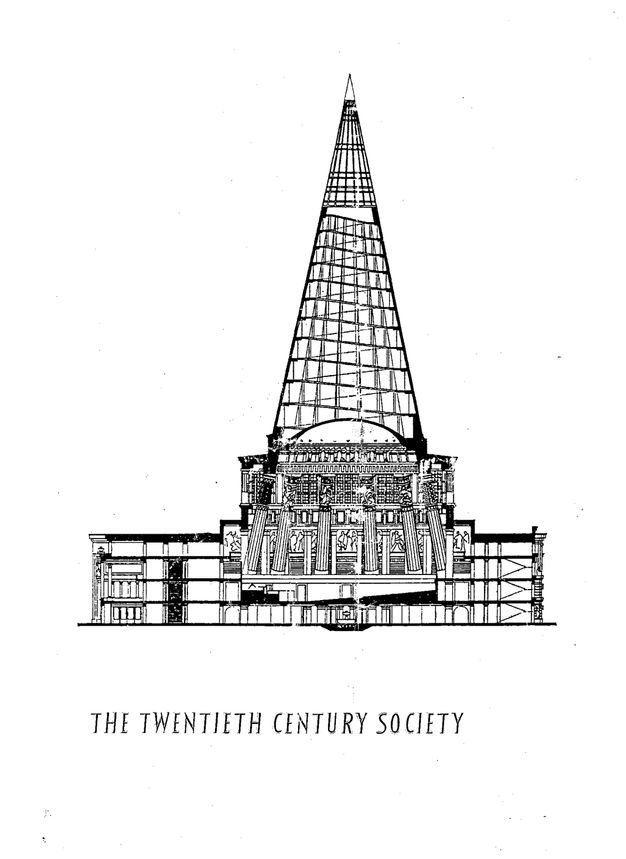

10To adapt an architectural analogy, in what follows I will combine the long section of Stamp’s life—a biographical account following a chronological narrative—with a cross section that seeks to show how all the various parts of his life’s work—scholarship, journalism, campaigning, graphic design, television, exhibitions and teaching—were bound together by a single purpose. For Stamp pursued his causes across diverse platforms: scholarly monographs, lectures, magazine articles, broadcasts, tours, graphic art and exhibitions. As Timothy Brittain-Catlin has argued and as encapsulated by Stamp’s corpus, a more enriched architectural culture, including the rediscovery and reinterpretation of subjects that may not appear on the academic radar, depends on a vast variety of platforms and voices.11 After all, much of the make-up of architectural history in Britain had developed through journalism, and has, according to Adrian Forty, “always occupied an ambivalent relationship to universities and academia”.12 Architectural history has also been shaped by the activities of the voluntary groups in which Stamp was active, including the Georgian Group, the Ecclesiological Society, the Lutyens Trust, the Alexander Thomson Society and especially the Victorian Society and the Twentieth Century Society (formerly the Thirties Society), both of which were effectively professionalised during Stamp’s active membership.13

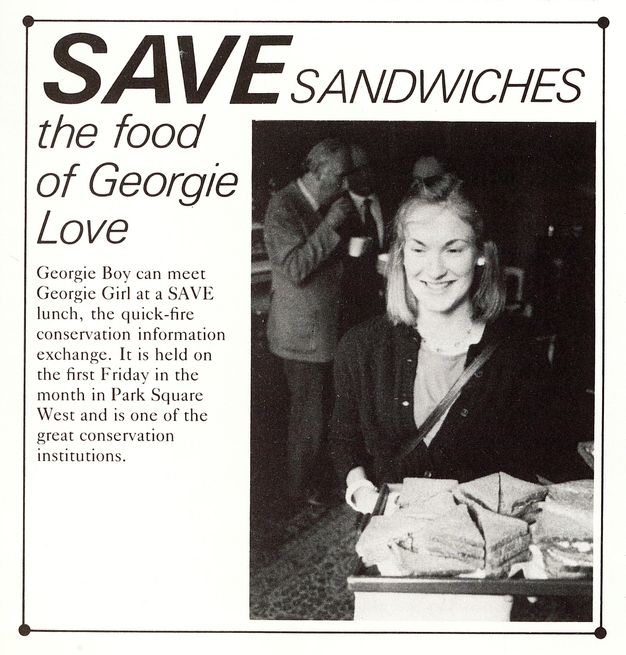

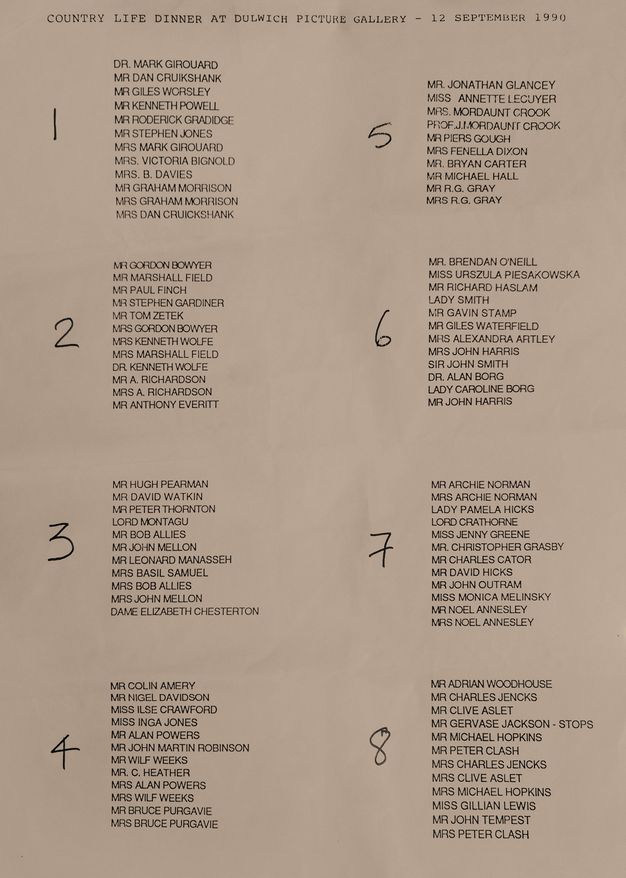

11This article positions Stamp in the historiography of the late twentieth- and early twenty-first century discipline as an activist-scholar, a lively tradition curiously missing from David Watkin’s seminal disciplinary history of 1980, and as a figure who worked across a broad fusion of intellectual modes that have received little scholarly attention.14 The focus is on early rather than late Stamp as this article holds that Stamp’s posthumous reputation has been shaped primarily by his earlier work and outlook.15 Furthermore, I situate Stamp in a series of lateral centres, the key informal fulcrums around which were formed Stamp’s alliances and friendships, which helped to fuel the modern conservation movement in Britain. These included Benjamin Weinreb’s bookshop in London’s Great Russell Street and the lunches, those “quick-fire conservation exchange[s]” in London’s Park Square West, of SAVE Britain’s Heritage (fig. 3).16 Beyond his homes in Southwark and King’s Cross, London, and Strathbungo, Glasgow, other nexuses for Stamp in London included the Bride of Denmark pub at the Architectural Press; the Drawings Collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA); the Art Workers’ Guild; and St Mary’s, Bourne Street. While these centres show architectural history thriving outside the academy, they also reinforce its exclusivity as a discipline developed informally by a tightly woven, largely male and relatively affluent elite (fig. 4).

14

By the time of Stamp’s death, Anthony Geraghty recognised that he had “enjoyed a higher profile than any other architectural historian of his generation”.17 Geraghty added, “I remember knowing of him when I was at school . . . there’s no way I would have heard of any other architectural historians [at that time]”.18 It is difficult to quantify Geraghty’s claim but a hint is offered by Hélène Lipstadt who had recognised in 1982 that Stamp had unusual reach for an architectural historian and was “a man to watch. This is not hard to do for [he] appears everywhere, from the pages of the T.L.S. to the A.A.”.19 Following a pendulum shift in the 1970s, the increased dominance of the New Right in political and cultural thought helped Stamp find a large audience and some fame as a journalist at Private Eye (if pseudonymously), the Spectator and the Daily Telegraph. He went on to enjoy a public persona beyond his scholarly articles and books as a columnist (at different times) for the Independent, the Scottish Herald, the Scotsman and Apollo, as well as through television work for the BBC and Channel 5.

17Stamp’s oeuvre was that of a public intellectual, designed to help (re)create and sustain a public discourse around architecture. As Ian Jack put it, “it was Stamp, arguably more than any writer since Betjeman, who made sure that architecture remains high in the list of British public concerns”.20 Or as Ian Hislop, editor of Private Eye, remarked of Stamp’s journalism, “The truth is that people would go with him. If Gavin was interested then the reader would be [too]”.21 Stamp therefore had much in common with Betjeman, as well as Nikolaus Pevsner, in his ability to engage with a lay public in the reassessment of English (and later Scottish) architecture.22 If the hallmark of his work was his emphasis on raising public awareness, this relied, as we will see, on constant and inventive advocacy. Stamp and his network were interested in finding strategies to imaginatively bridge past and present—or even to offer “a direct bridge to a distant past”, as he described early architectural photography (an enduring passion).23

20Stamp was at times seemingly out there on his own, “the poor architectural critic, always Seeking After Truth”.24 This is reminiscent of the architectural historian and activist James Marston Fitch (1909–2000), who was scathing of the sycophantic mainstream architectural press, which had produced “a literature hermetically sealed against reality—auto-intoxicated, self-congratulatory, elitist, and suffocatingly smug”.25 Stamp was there to offer accountability in the UK context. Whereas Joan Ockman raised her concern in 2017 that research is slowly replacing critique in architecture (“it eschews tendentiousness, preferring to ‘defer judgment’”), Stamp’s corpus was cumulatively a work of criticism and of judgement, where his binary position on what was right and wrong was often stubborn and unrelenting.26 As an activist-scholar, his work was one big campaign—and to campaign one had to be for or against things.

24Stamp had his own critics. For instance, in the wake of the Mansion House Square inquiry of the 1980s, the artist and polemicist Patrick Heron saw Stamp as representative of “a flood of architectural journalism that is quite unprecedented in the way it substitutes gossipy denigration for critical formal analysis”.27 The journalist Paul Finch, furthermore, found Stamp’s diatribes “far too ad hominem”.28 Stamp’s criticism often lacked nuance, and he was quick to denigrate his detractors. Stephen Games, publisher and journalist, was one of many who were irritated by his “messianic” style and “black–white” polemics.29 Typical of this controversial style is Stamp’s judgement of William Whitfield’s swansong, Juxon House, Paternoster Square, London (2003): “my objection . . . is not that it is (sort of) Classical, not that it is Not Modern, but merely that it is bad”.30 Yet, as A. N. Wilson put it, “Gavin didn’t compromise in any way. That was missed by Ian Hislop, who wanted to make him a balanced journalist at Private Eye. But the whole point about Gavin was there only was one point of view”.31 His work, reminiscent of A. W. N. Pugin’s and John Ruskin’s, was shaped by a moral-aesthetic position on what he passionately felt was right or wrong.32

27What exactly constituted right or wrong could sometimes be hard to discern. Given the sheer breadth of his interests and political shifts, Stamp could appear inconsistent and enigmatic. A case in point comes from a letter to Stamp from Charles Jencks of 27 November 1987. Its jocularity suggests mutual affection and is a reminder that a sense of fun, as much as a moral seriousness, pervades Stamp’s work.

Dear Sir Stamp

I realise you’re a paid up Member of the Art Workers Class and the Georgian Socialistic Cooperative, but your recent Invitation to listen to the Modernist talk at the Entre-Deux-Guerres Society comes as a surprise.

Are you also a member & Chairman of the Forties, Fifties, Sixties, Seventies & Nineties Society?

Are you All Things to All People? Will the real Stamp sit down? I am now so confused as to your identity that on the nights of the 5th & 6th I would ask you to wear a Red Boutonnière for the Workers and a Blue one for the Georgians, so I can recognise you.

And you realise you have to be an Architectural Critic on December 12th and come to our meeting at the Royal Society, 6:00–8:30 to Drink and Debate the Role of the Critic (or your identity).

Young Fogeyism

Stamp attended Greenhayes School for Boys in West Wickham (circa 1953–59) before going on to Dulwich College (1959–67), originally as a beneficiary of the “Dulwich Experiment”, the initiative of the master and educationalist Christopher Gilkes that secured local authority funding for academically bright students.34 Charles Barry junior’s Dulwich College (1866–70), Stamp recalled in 2017, was “the beginnings of my architectural education”.35 It also formed the basis for his first piece of architectural history—and invective. In the face of a feeling of utopianism in the air in the 1960s, and demonstrating his early impatience with those who did not value the past, he implored the college to value and safeguard its historic built environment.36 He later recalled being “deliberately bad” at games (as a reaction against his father’s masculinity), which enabled him to spend Wednesday afternoons in the art room.37 Yet, his interest in designing and making objects had been nurtured even earlier. Stamp remembered visiting his uncle Rosse Stamp, a scientist who had worked for the Admiralty, whose home was “full of clocks and other devices that he had designed and made himself, including curious machines which successfully delighted his young nephew”.38 He therefore went on to understand architecture not only as a historian but also as a maker. One early result was his modelling, in cardboard, of a Victorian train with articulated carriages (fig. 5).

34

In 1967, aged nineteen, Stamp made his first trip to the northern industrial cities of the United Kingdom. Witnessing changes that were hard to stomach, he saw modern architecture “as a form of terror destroying so much that I loved”.39 The following year he matriculated at Cambridge University, where he studied history for two years at Gonville and Caius College, but he was keen to focus on architecture and transferred to the fine arts faculty for the second part of the tripos (established by Michael Jaffé).40 However, Stamp found that the belief in “a ludicrous Utopia” held by architectural students in the Department of Architecture at Scroope Terrace “turned me off completely”. For instance, the long-serving head of department, Leslie Martin, had only recently published his ill-fated Whitehall scheme of 1965, which planned to replace the historic government district with a concrete megastructure.41 Looking back, Roger Scruton, a fellow at Peterhouse (1969–71), captured a Stampian sensibility in his memoir, describing “the aesthetics of modernism . . . [as] an attempt to remake the world as though it contained nothing save atomic individuals, disinfected of the past, and living like ants within their metallic and functional shells”.42

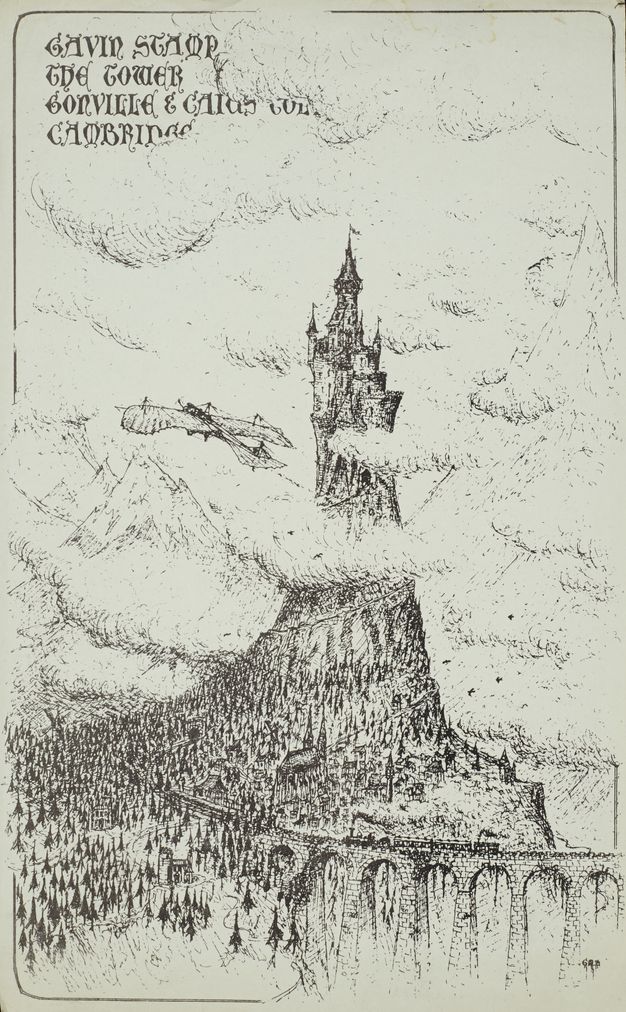

39While Stamp subscribed to an anti-modernist view of the past, he took issue less with modernism per se than with the people whom the modernists extolled as heroes. As Jonathan Meades suggested, “it was not so much the buildings that he objected to as the shrill manifestos, pious bombast and ludicrously pretentious claims which were attached to them”.43 Stamp found romantic refuge in rooms high up in Alfred Waterhouse’s Tree Court building (1870) at Caius, which he captured in a fantastical drawing “resembling Gormenghast” (fig. 6).44

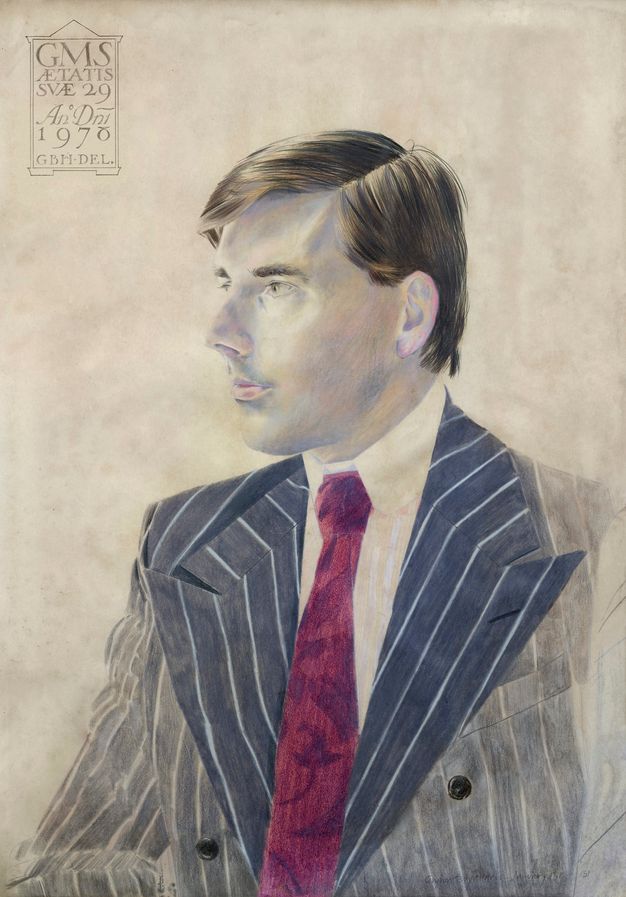

43Stamp was one of the first generation of the coterie of talented male students mentored by David Watkin (1941–2018), fellow of Peterhouse, which along with Selwyn and Christ’s was one of the centres of the Cambridge right.45 The oldest of the Cambridge colleges, Peterhouse was, as Michael Gove put it, “charmed by an environment defiantly at odds with the temper of the times”.46 Like Watkin—captured by Stamp in a 1970 photograph—Stamp’s own sense of timelessness and shifting political leanings were signalled sartorially (fig. 7).47 He wore double-breasted pin-stripe suits, ties and Edwardian starched collars. As a limerick on his twenty-first birthday from a Cambridge contemporary began: “I once knew a man called Stamp / Whose style was incredibly camp”.48 Reminiscent of the interwar Oxford Hypocrites’ Club of Evelyn Waugh, Robert Byron and his circle, Stamp liked to dress up to appear markedly against the post-Second World War consensus.49 However, Stamp admitted that he had habitually worn jeans as a boarder at Dulwich College and had even attended a Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament march.50 But he moved to the right as an undergraduate and was now unlikely to espouse popular causes. The so-called Peterhouse Right—or “Peterhouse High Tory Tomfoolery”, to use Alan Watkins’s words—was an exclusionary fraternity of dons united by a hatred of liberals, that is seen by some commentators as having laid the intellectual foundations for the modern conservatism of Margaret Thatcher.51

45

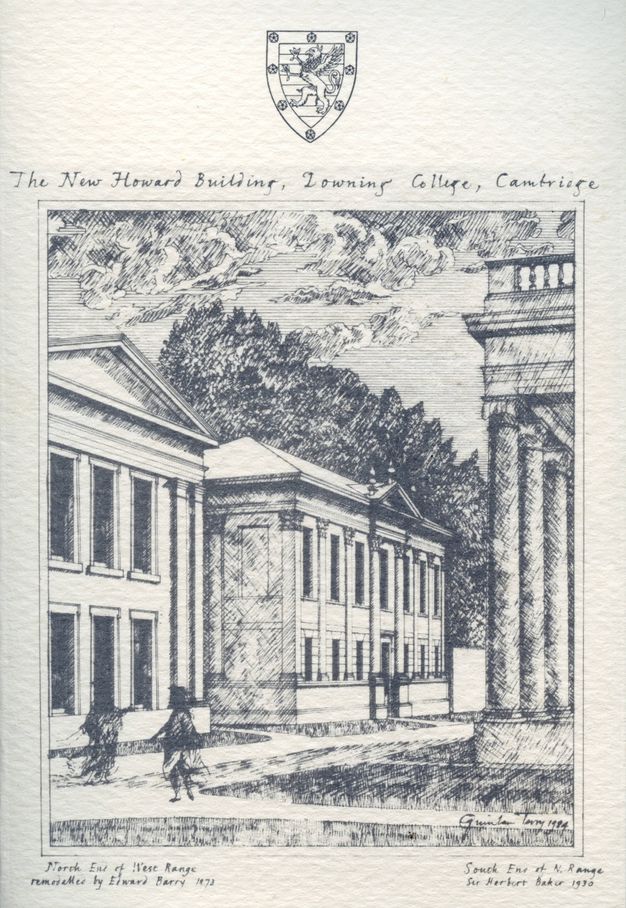

Watkin later published Morality and Architecture, a polemic critiquing the deeply rooted modernist and determinist orthodoxy of architectural history.52 While these thoughts were codified in the book in 1977, the germs of his thesis had been aired at Cambridge in 1968.53 Its targets ranged from the Gothic propagandising of Pugin to the modernist propagandising of Pevsner—in Stamp’s words, Pevsner’s “pathetic subjugation to a Hegelian notion of the moral supremacy of the zeitgeist”.54 Watkin was a hard-line classical revivalist whose career focused on expounding the careers of historic figures who espoused the eternal values of classicism. His 1977 exhibition The Triumph of the Classical: Cambridge Architecture, 1804–1834 at the Fitzwilliam Museum, which can be seen as an extension of Morality and Architecture, included a model made by Stamp of the aborted east range of C. R. Cockerell’s design for Cambridge University Library (circa 1836), now Gonville and Caius Library (fig. 8). In 1982 Stamp was described by Lipstadt as no less than the leader of the Watkinites.55 After all, Watkin had been incredibly supportive of Stamp as a student, as their surviving letters reveal.56

52Detractors of the Peterhouse Right, according to Susie Harries, saw it as “a caucus of reaction in Cambridge, a collection of self-appointed right-wing penseurs with aspirational lifestyles and déclassé origins”.57 Watkin entertained in a grand set in St Peter’s Terrace and had a flat in Albany, Piccadilly, but his background, as the son of a salesman for a builder’s merchant, was modest.58 Not unlike Stamp, Watkin was a model of post-war social mobility, having gained a place at Farnham Grammar School, benefited from the county scholarships offered under the Butler Education Act and won a scholarship to Cambridge. Yet the world he created, as he saw it himself, was “essentially an aristocratic, or would-be, aristocratic one: High Tory, High Catholic, and High Camp”.59 He was formatively influenced by Monsignor Gilbey (1901–98), the atavistic Catholic chaplain of the university from 1932 to 1965 (fig. 9). A deeply reactionary man, “spiritually and psychologically, [Gilbey] remained undetachable from the late Victorian world”.60 When in the 1960s and 1970s most of the intelligentsia were left-wing, those who were right-wing stood out. Stamp was therefore a conspicuous part of a fraternity of architectural neoconservatives, or what Reyner Banham described as “the lunatic core . . . the New Architectural Tories” or “the National Trust Navy, those roving bands of mansion-fanciers and peerage-buffs”.61 This was a reactionary youth movement, a generational recoil later self-parodied as “young fogeyism”.62

57

Peterhouse was also a world of effete aestheticism. It played host to the secretive male-only Adonian Society, and Watkin himself presided over the later Cocoa Tree Club, described in a letter to Stamp from October 1984 as “a new dining society dedicated to tradition, Conservation [sic] and intellectual conversation in a most agreeable atmosphere. The club is, needless to say, named after the meeting place of the Hanoverian Tories, under Sir Thomas W[yndham], during Walpole’s tenure of power”, namely the Cocoa Tree coffee house, Pall Mall.63 Furthermore, this coterie was a breeding ground for right-wing journalism. In the Cambridge Review, edited by one of Stamp’s tutors, John Casey, “the wing-collared English don” and founder of the Conservative Philosophy Group, Stamp published an early architectural polemic on James Stirling’s history faculty library, Cambridge (opened in 1968), which he found wanting aesthetically, environmentally and functionally.64 This helped him establish his reputation and find his way as a journalist.

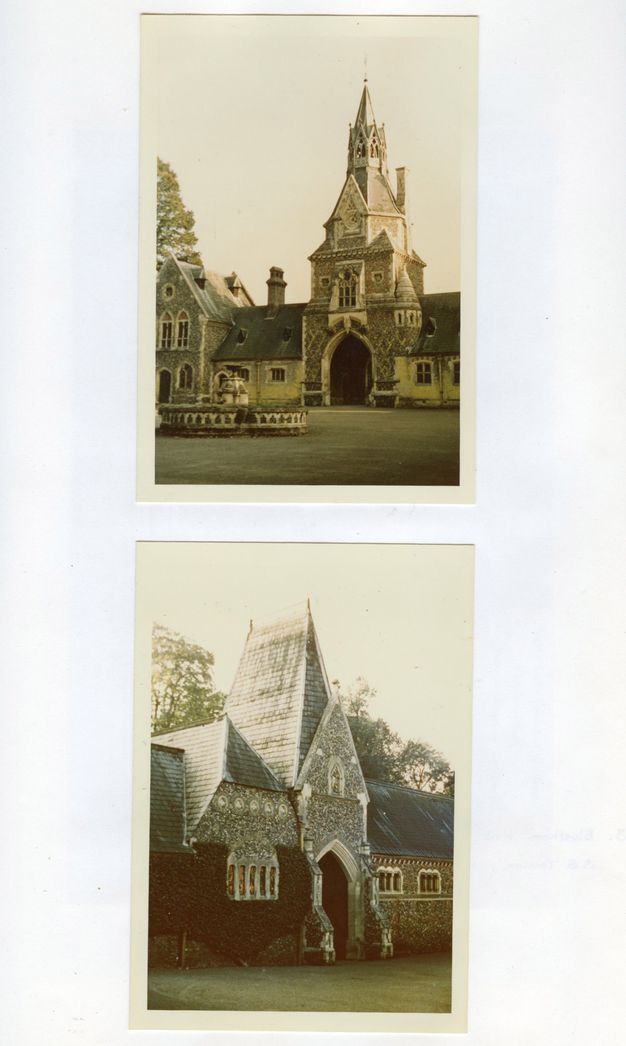

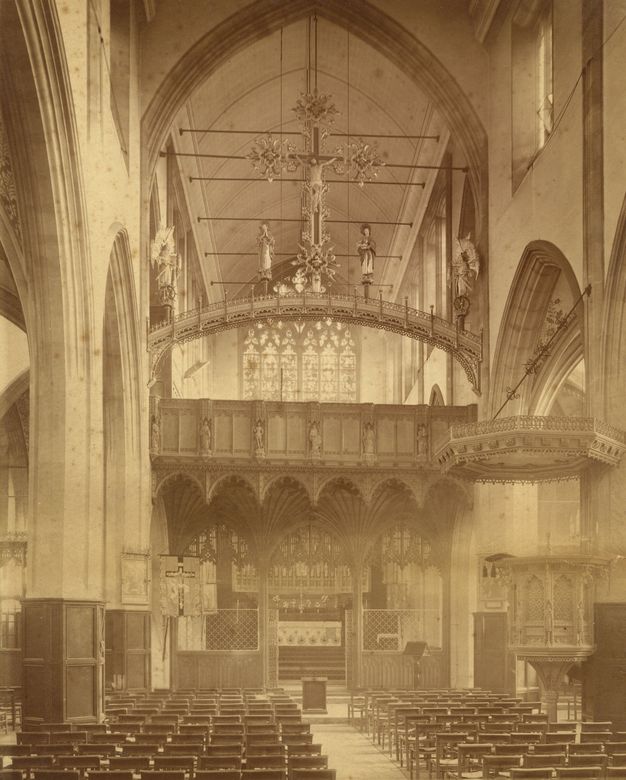

63Stamp’s student work demonstrates his interest in examining alternatives to the standard norms of twentieth-century praise. His undergraduate thesis, “High Victorian Rogue Gothic Architecture” (1971), displayed his proselytisation of obscure, forgotten, often wilful architects, who had been characterised by H. S. Goodhart-Rendel in 1949 as “rogues” (figs. 10 and 11).65 They challenged the hegemony of High Church taste and many faced a hostile reception in the twentieth century. Stamp’s doctoral thesis examined the transition of High Victorian muscular Gothic to refined Gothic.66 His protagonist was the “brilliant and peculiar, and very little known” George Gilbert Scott junior (1839–97), who offered “the best of all possible worlds: drunkenness, adultery and insanity”.67 In his domestic architecture he belonged to the Queen Anne avant-garde, while a late Gothic manner informed his churches, such as St Agnes, Kennington Park (1874), in opposition to the orthodoxy of the English Middle Pointed (fig. 12).68 Scott junior played a key role in the reaction against the pursuit of the ideal of “development” championed by Charles Eastlake in The Gothic Revival (1872), which informed subsequent interpretations of the subject, “an expression of the ‘Biological Fallacy’”, as Stamp put it.69 He was referring to a term employed by Geoffrey Scott in The Architecture of Humanism in 1914. Watkin’s foreword to the 1980 edition of the book summarises Scott’s position on nineteenth-century architectural theory as “the attempt to decide architectural right and wrong purely on intellectual grounds [which remains] precisely one of the roots of our mischief” in the present discipline.70 Stamp himself had offered further historiographical context for his doctoral work in 1975:

6571The effect of the arrival of Pevsner on the scene was to regard Victorian architecture, selectively, as a progression towards Modern Architecture . . . Out of the fog are pulled the bright progressive lights: Pugin, Morris, Webb, Mackintosh. Summerson resurrected Butterfield brilliantly, because he seemed to be dada—anti-art, aggressive, original, but Reginald Blomfield’s book on Norman Shaw was belittled as Blomfield saw Shaw’s style leading, not towards modernism, but to the revival of the Great Classical Style.71

In the 1960s and 1970s late Victorian architecture was still off beam, an almost lost generation awaiting retrieval. As Michael Hall put it, “one aspect of the nineteenth-century architectural legacy that had a particularly poor reputation as a result [of a Whiggish emphasis on ‘progress’] was the Gothic Revival after about 1870”.72 Robert Furneaux Jordan’s Victorian Architecture (1966) was a case in point; Stamp described it as “a blinkered Hegelian view of the 19th C. [sic]” and its author as “an erratic communist [by which he meant from the liberal left] of the Festival of Britain vintage”.73 Reflecting contemporary architectural factionalism, Stamp often used “Marxist” and “communist” as terms of abuse, while the term “fascist” was used to describe figures of the New Right.74

72Stamp was an early beneficiary of the post-war, primarily German-Jewish and Colvinian, raising of standards for history and architectural history.75 Like Stamp, the architectural historian Howard Colvin was an empiricist rarely prone to speculation, who prioritised history over theory, stressed the importance of archival research and championed architectural biography. Stamp’s methodology was established at Cambridge and developed throughout his career, which centred mainly on named architects, in line with the prevailing Colvinian emphasis.76 Although Stamp rarely offered methodological scaffolding for his work, it was primarily retrievalist and can be seen as akin to fandom, a method “of passionately (lovingly, angrily, slavishly) reworking canonised icons”.77 In offering a rationale for the subjects of his retrieval, Stamp often subscribed to a genius narrative—for instance, the thesis of the unknown genius pervades his work on the architect Alexander Thomson—that has become increasingly outmoded and, as argued by Christine Battersby, is also misogynistic.78

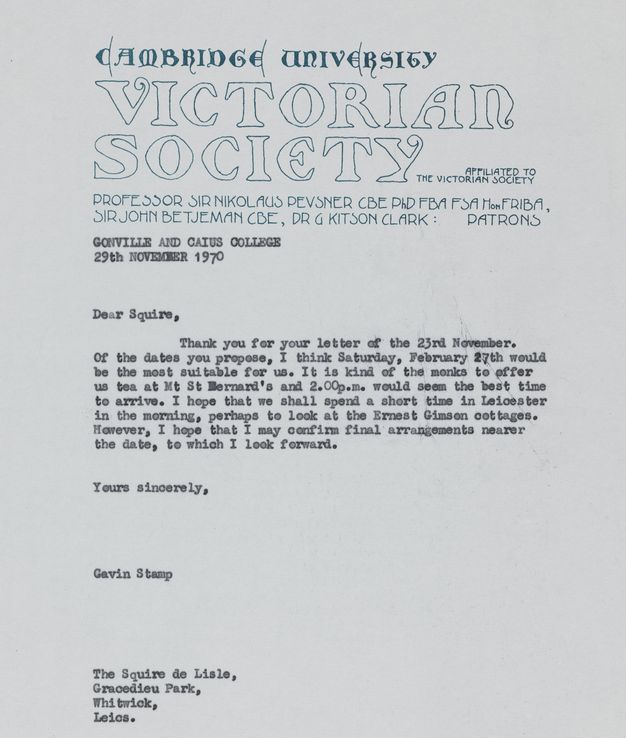

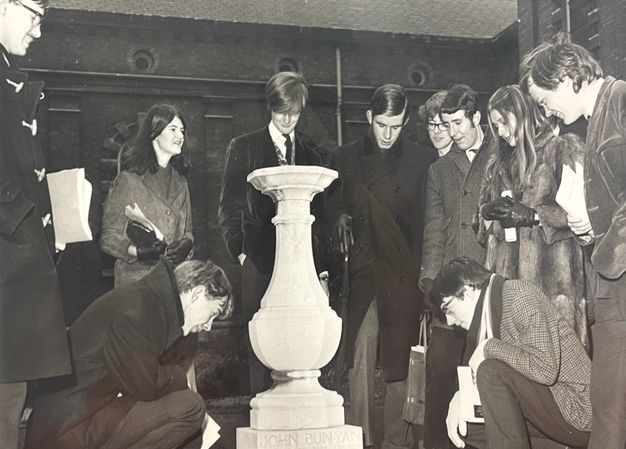

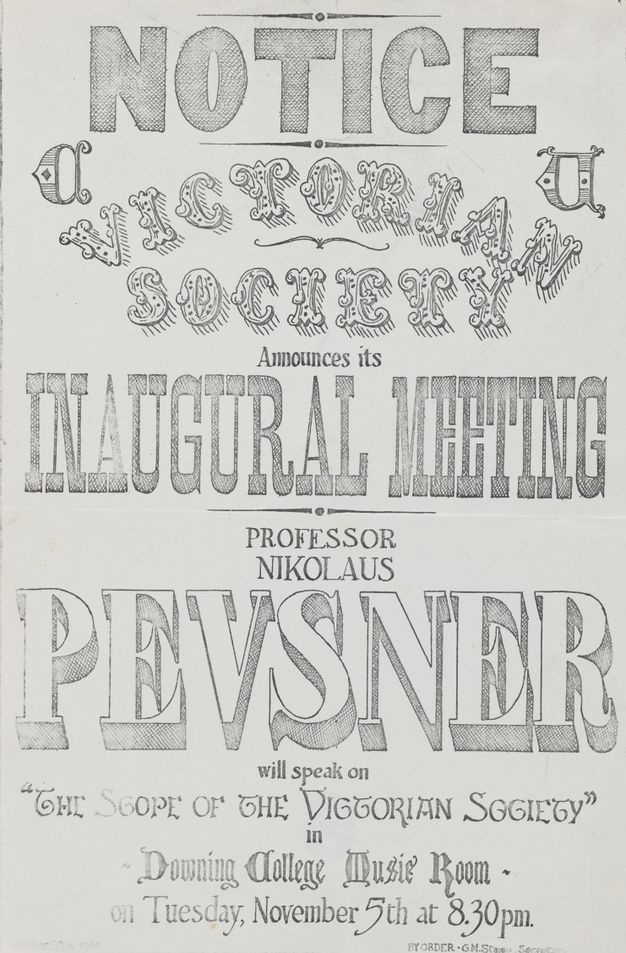

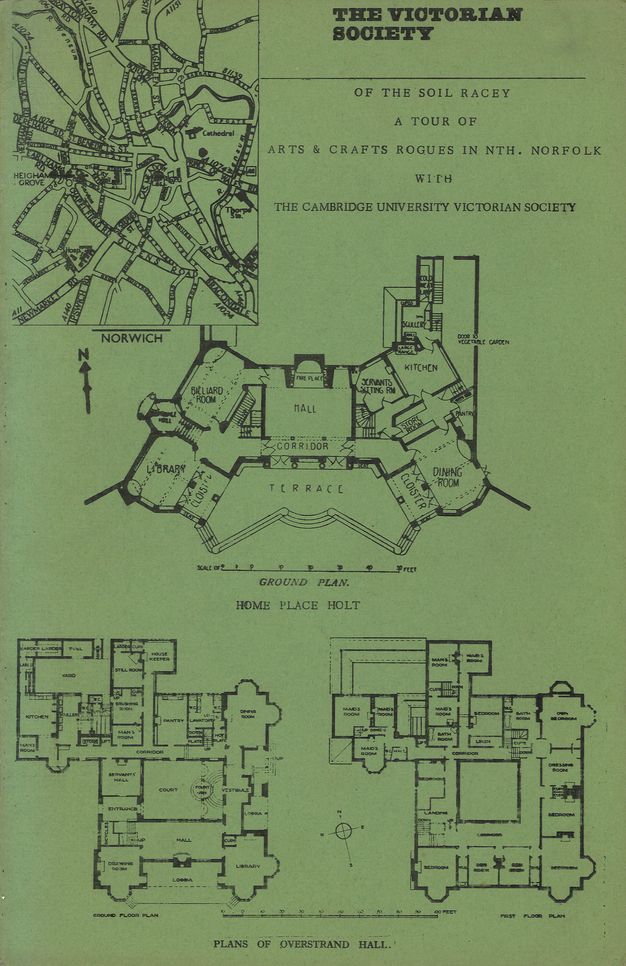

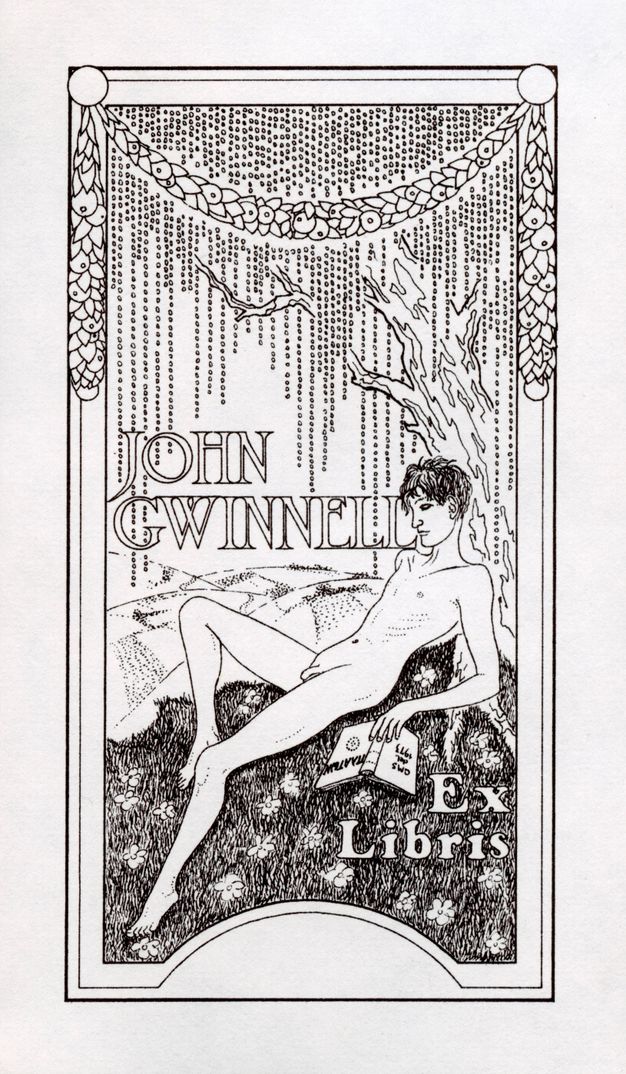

75It was at Cambridge that the roots of Stamp’s career as an activist and grassroots organiser were laid, with his foundation in 1968 of the Cambridge University Victorian Society (CUVS), affiliated to the national society.79 He displayed an early enterprising spirit and a talent for bringing people together.80 The CUVS organised trips and talks and played an active role in campaigns, for instance supporting Holy Trinity Church, Reading, in its appeal to rescue the Pugin rood screen from St Chad’s, Birmingham, in 1969 (figs. 13, 14 and 15).81 Here too Stamp displayed initiative in experimenting with tools to popularise the hitherto unseen and forgotten, such as the walking tour (fig. 16).82 As though modelling an anti-ugly aesthetic himself, Stamp also designed the shopfront and lettering for the Victorian-era Waffles cafe at 62–64 Fitzroy Street, Cambridge, for Pat and Virginia La Charite in 1973, along with menus and letterheads (fig. 17).83 He also took part in jobbing work as a self-taught draughtsman and continued with his patchwork freelance career throughout the 1970s and 1980s, including designing bookplates both for himself and for those in his network, including Watkin, Colin Amery, Peter Freeman and his fellow Caius student John Gwinnell (fig. 18).84

79

After many decades away from Cambridge, Stamp returned to Caius as a bye-fellow from 2002 to 2004. The Revd Francis Bown, an old friend, congratulated him: “I see you now as the Hugh Plommer de nos jours: wise, articulate and fearless, that Defender of Truth and Tradition against the mindless liberalism and false egalitarianisms of the Age (and of the universities)”.85 William Hugh Plommer (1922–83), a former lecturer in classical architecture who had lectured to Stamp’s cohort in the 1960s, and later taught with him, had been a vocal critic of modern architecture in Cambridge. Stamp never became fossilised in the fogey mode, however, but outgrew and even renounced it. Looking back in 2017, he described himself in his student years, as though haunted by them, as “gauche, posturing, silly, naïve, pretentious”.86

85Curating and Campaigning

Stamp moved back to London in the early 1970s at a creative time for conservation activism. The Civic Amenities Act of 1967 had created conservation areas and strengthened the power of amenity groups, while the Town and Country Planning Act of 1968 introduced the legal necessity for owners of listed buildings to apply for consent if they planned to alter or demolish them. Stamp’s move closely preceded the European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, the year of the watershed Destruction of the English Country House, 1875–1975 exhibition at the V&A, and the foundation of SAVE Britain’s Heritage, which anticipated the foundation of the Spitalfields Trust in 1977 and the Thirties Society in 1979. Almost as a counter-cultural gesture, Stamp took up residence at the top of the former clergy house of St Alphege, Pocock Street, Southwark (fig. 19). He decorated it with wallpaper from Watts & Co. where he worked as a freelance consultant with his friend (and former supervisor) the architectural historian and Anglican (later Jesuit) priest Anthony Symondson (1940–2024), helping to keep the spirit of Victorian ecclesiastical and domestic needlework and embroidery alive.87 They chronicled the company history and redesigned several catalogues, adding new designs rediscovered in 1975 such as Pugin’s Rose and Coronet wallpaper (circa 1848).88 Persuading clergy to choose something traditional for frontals, copes, stoles and so on in suitable decorative fabrics aligned with Stamp’s anti-ugly remit as articulated a decade later in The Church in Crisis.89 He occasionally designed objects himself for Watts & Co., too (fig. 20).

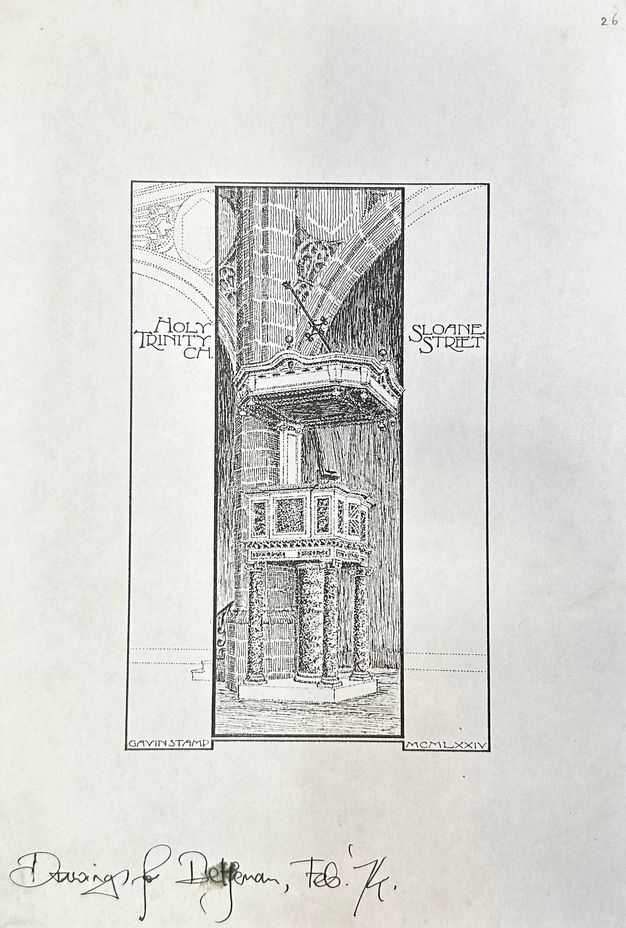

87Pocock Street was the appropriate base for Stamp to launch his campaigns on behalf of old buildings, including one of the hardest fought by Betjeman, in 1973–74, concerning the threat of demolition of the church of Holy Trinity, Sloane Street (J. D. Sedding, 1890).90 The owner (and churchwarden), Lord Cadogan, and the rector, the Revd A. B. Carver, claimed that the building was too expensive to maintain and sought to develop the site with a new church and flats. In August 1973, Betjeman had asked for Stamp’s assistance not as a writer but as an artist. This was prompted by a recent commercial enterprise by Stamp, a series of prints of “architectural phantasies” forming The Architect’s Calendar (1973), bound with wallpaper by the architect George Frederick Bodley, courtesy of Watts & Co.

90Betjeman was “enchanted” with Stamp’s resulting drawings, which “give far more the quality of the church than could a photograph” (fig. 21).91 They were initially offered to the rector to be sold to aid restoration efforts but were refused, and thus a pamphlet of four drawings, along with Betjeman’s appeal, was offered for sale to the public.92 The resulting publicity was considerable and the building was saved. The campaign revealed the vulnerability of historic churches under existing legislation, namely their exclusion from listed building controls.

91

Stamp had met Betjeman in the Bride of Denmark pub at the Architectural Press in Queen Anne’s Gate. The Bride had been conceived in 1946 by the chairman of the press, Hubert de Cronin Hastings, and became a hub for architectural journalism—while it lasted. When it became known in 1990 that Robert Maxwell was to buy the press and relocate it to Clerkenwell, the cartoonist Louis Hellman wrote to Stamp: “It seems Capt. Bob [Maxwell] is busy destroying the most important architectural publishing company in the world . . . Bride of Denmark raped . . . Shock horror”.93 In the Bride’s last days, Stamp lamented:

9394I have spent far too many happy hours by the bar, drinking far too much of the Architectural Press’s whisky and discussing the latest architectural gossip and ideas for articles . . . [it is] the soul of the publishing house that has been at the very centre of English architectural life for almost a century.94

The appropriately neo-Victorian setting of the Bride was Stamp’s social base in the 1970s and 1980s.

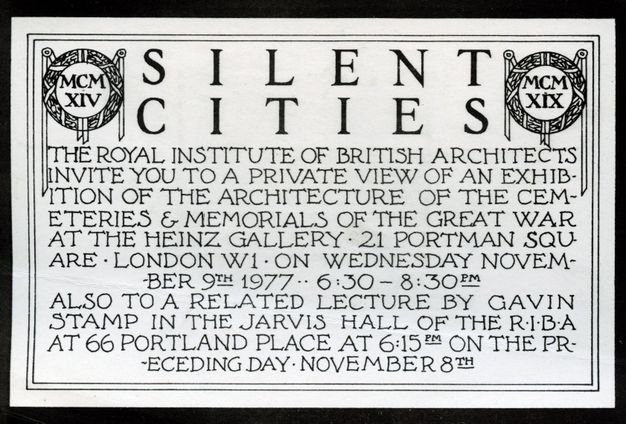

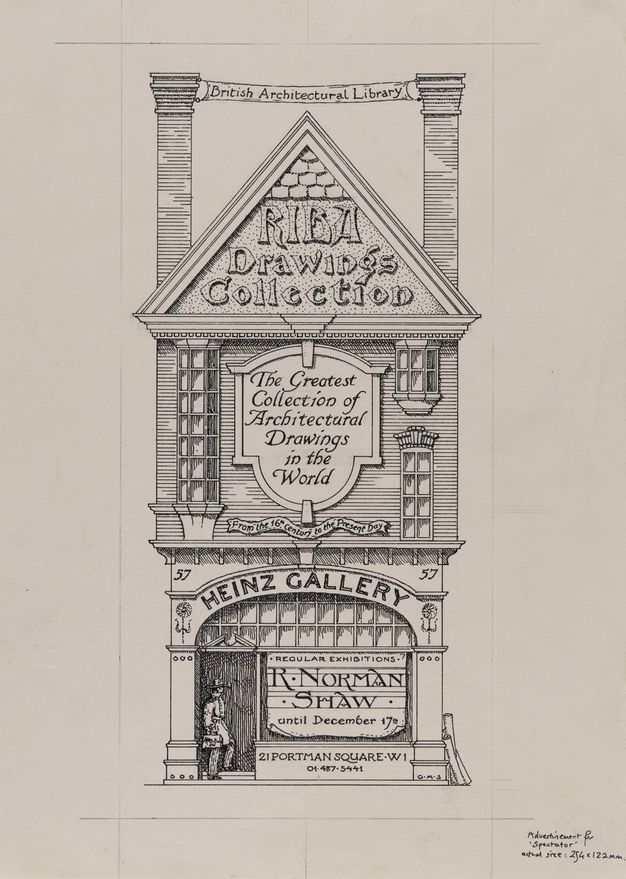

One of Stamp’s principal (and enduring) preoccupations of those decades was the Great War. He mounted the Silent Cities exhibition in 1977 at the RIBA’s Heinz Gallery (fig. 22), which had been established in 1972 with funds from Drue and Henry Heinz, focusing on the work of the principal architects of the Imperial War Graves Commission, including Sir Edwin Lutyens.95 Countering Pevsnerian functionalism, Stamp quoted Lutyens in his catalogue: “Architecture with its love and passion, begins where function ends”.96 On receiving the catalogue, Betjeman described the exhibition (in terms that seem hackneyed today) as “a herald of the new dawn after Bau Hause [sic] blackness for what seems centuries”.97 Betjeman praised the catalogue (designed and lettered by Stamp) as resembling the work of Mervyn McCartney, a pupil of the architect Richard Norman Shaw and a founder of the Art Workers’ Guild, who edited the Architectural Review between 1905 and 1920.98 Incidentally, Stamp had also co-organised the Norman Shaw exhibition (with Andrew Saint) at the Heinz Gallery the previous year (fig. 23).

95Stamp invited Oswald Mosley (1896–1980) to speak at the opening of Silent Cities on Armistice Day 1977.99 Mosley, then living in Orsay, had fought on the Western Front, returned as a war hero and become a Tory member of parliament, aged twenty-two, before shifting politically to the right and founding the British Union of Fascists (fig. 24). To Stamp, he was a rare living representative who remembered what the First World War had been like. He had also known Lutyens.100 Mosley accepted the invitation.101 As Stamp explained to him: “my views do not impress the cowardly bureaucrats and leftist fellow-travellers at 66 Portland Place [RIBA headquarters]—mediocre architects who still worship two of the real evil influences of this century, Corbusier and Gropius”.102

99

The incumbent RIBA president, Gordon Graham, and the RIBA librarian, David Dean, shut the idea down. As Dean put it to Stamp on 21 October 1977, “It was simply a striking idea which, in this sublunary world, wouldn’t work”.103 Stamp, who was forced to disinvite Mosley, sent a letter of apology to him as follows:

103104For you to speak . . . at an exhibition about the memorials to the dead . . . not about politics but about that war and what it meant to you would be of harmless and [of] very great interest, but as you will understand, the RIBA are terrified that any association between you and the Institute will outrage the left-wing power-seeking architects on their Council. I know well that if (fortunately impossible) I were to invite Stalin or Andreas Baader . . . to speak . . . there would be scarcely a murmur from them. Such is the nature of the so-called liberal establishment which, with double standards, dominates this country.104

Astragal at the Architects’ Journal and Scorpio at Building News criticised the idea publicly.105 Stamp defended himself to the editor of the last in a letter facetiously signed “Reichstag”.106 As a historian who frequently used oral historical methods, he was trying to anatomise a historical moment to retrieve its truths. However, he compromised his intention as his polemicist instincts meant that he could not resist being provocative in making a point about leftist intolerance by choosing Mosley to speak.107

105Another Heinz Gallery exhibition, London 1900 (1978), had been a further early manifestation of the young Stamp’s anti-Pevsnerian mode. To Betjeman it was “a glorious tonic”, while to Watkin it was “a doctrinal exhibition . . . [that has] an eagerness to proselytise”.108 A special issue of Architectural Design that Stamp guest edited in 1979 on “Britain in the Thirties” was furthermore “a deliberate antidote” that set a historiographical tone for studying the period pluralistically (and acerbically), if with only limited attention to modernism.109 Stamp enjoyed a rich and regular correspondence with John Summerson from the late 1970s up to the latter’s death in 1992. He brought Summerson along with him as he himself was coming to terms with the architecture of the recent past, which the latter desired to take “seriously, i.e. non-nostalgically” (fig. 25).110 Summerson expressed empathy with Stamp’s “anxiety to see the thirties whole”:111 “I cannot but agree with your last sentence [of “Britain in the Thirties”], ‘confused, tortured . . . rather unattractive! Yes, indeed!’”112

108

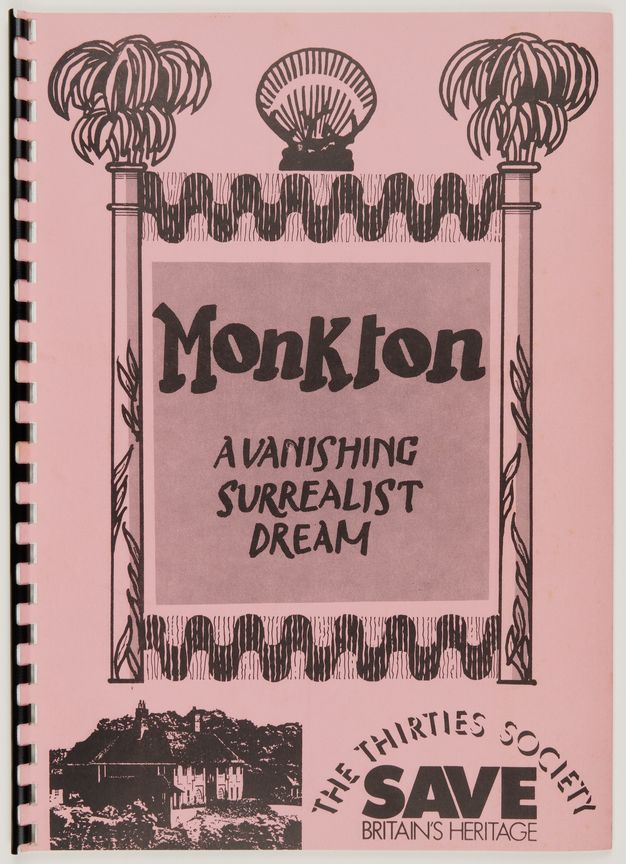

In 1979 Stamp had been one of the founders of the Thirties Society (renamed the Twentieth Century Society in 1992). While he had been very active, he did not occupy a particular position until he succeeded Bevis Hillier as chairman in 1983 and continued in the role until 2007. Stamp contributed to the society’s new journal from its inauguration in 1981 which Summerson, savouring the early volumes, referred to it as Stamp’s “annual horror comic!”113 One of the many campaigns in which Stamp assisted was Monkton House, Sussex (1902), a Lutyens house transformed into a Surrealist fantasy in the 1930s by the bisexual socialite and Surrealist enthusiast Edward James (fig. 26). When the trustees of the Edward James Foundation sought to sell and disperse most of the house’s contents in 1985–86, Stamp supported their retention, finding the house “both perversely unique and yet curiously representative of its time”.114 In 1987 Stamp was a key figure in helping secure statutory protection for Bracken House, London (Albert Richardson, 1959)—incidentally the bête noire of the Anti-Ugly Action Group, a modernist architectural protest group founded in 1958 by students of the Royal College of Art—which became the first post-war building to be listed by the Department of the Environment. Stamp was also key in protesting the modernisation of London Regional Transport in the 1980s, which the Thirties Society feared would despoil the continuity of high design standards inaugurated by Frank Pick in the 1930s. Stamp is best known for shaping the heritage listing of the K2, the red telephone kiosk designed by Giles Gilbert Scott in 1929, whose wholesale replacement by British Telecom was imminent. An indominable campaign was mounted by the Thirties Society.115

113Stamp was heavily involved not only with the Thirties/Twentieth Century Society, but also the Victorian Society, the Georgian Group and other amenity groups.116 Their statuses owe much to Stamp’s involvement, especially in organising talks—notably a series on “Unfashionable Architects” for the Victorian Society (2000)—and walking tours, from “Wendingen: de Amsterdamse School en Dudok” (1973) in Holland for the Victorian Society with Roderick Gradidge to “Dudley and Wolverhampton” for the Thirties Society (1988).117 Stamp often used his critical platforms to champion causes informally on behalf of the amenity societies, even when he had less direct involvement with casework.

116In the late 1970s Stamp also began championing his causes through peripatetic teaching. From 1976 he lectured part time on the history of art tripos at Cambridge, originally on Victorian architecture but extending to “Post-War Architecture” by 1985.118 He also taught on several American programmes in London (Hollins College, 1974–90; Tufts University, circa 1982–88; University of Delaware, 1989; and New York University, 2005–12) and was particularly influential in shaping the Victorian Society in America London Summer School, which he led in 1976–82 and 1985–94.119 Between about 1980 and 1990 he was a part-time lecturer at the Architectural Association (AA) during Alvin Boyarsky’s chairmanship, at such a time as he self-consciously saw himself as “a reactionary historian . . . [who was there] to keep a balance”, especially, he probably meant, by critically questioning “the heroic role of the Left in both politics and architecture”.120 While his wide-ranging teaching included a neoclassical and Georgian lecture series, he was part of a pedagogical culture under Boyarsky that was, in Patrick Zamarian’s words, “decidedly eclectic”.121 As Alan Powers recalls, “Boyarsky liked to provoke the AA modernist establishment both from an avant-garde and a neo-traditional standpoint”.122 Furthermore, Robin Middleton (b. 1931), as general studies co-ordinator at the AA—who had also been an important intellectual (and sartorial) counterpart to Watkin at the art history department at Cambridge—was a strong supporter of Stamp whose own pluralism is reflected in his exhibitions at the school on Ernö Goldfinger (1983, with James Dunnett), Raymond Myerscough-Walker (1984) and Robert Atkinson (1989).

118Invective

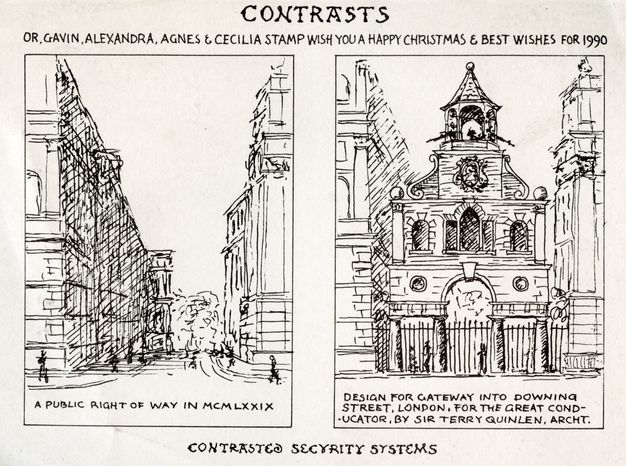

It did not take Stamp long to establish himself as the wittiest architectural historian of his generation—and he was trenchant with it, becoming a salient figure in “the new phase of the Puginian polemical tradition”.123 A case in point is his adoption of the Puginian trope of “contrasts” (fig. 27). His principal medium of invective, and his primary means of income for much of his life was journalism. In this capacity he was the apostolic successor to Betjeman but in his invective mode he could also be likened to other precursors. He had rapt admiration for the urban writer Ian Nairn (1930–83). Another apostle of Nairn, Jonathan Meades, exchanged his thoughts on him with Stamp in 2001:

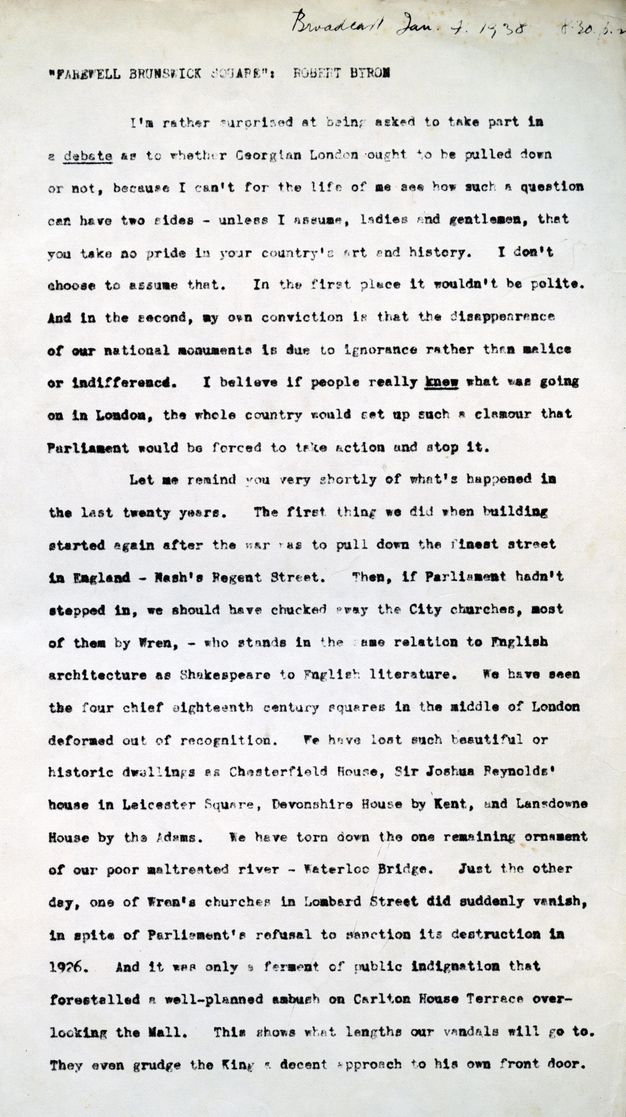

123Above all, Stamp saw himself as a disciple of the writer and critic Robert Byron (1905–41), modelling his architectural criticism on that of the Architectural Review “in its greatest days” in the interwar period, in spite of its being “a grimly propagandist organ for the ‘New Architecture’”.125 He admired its aim for a public critical discourse. During his short life, Byron had a freelance journalistic career. He was one of the biggest champions of Lutyens’s achievement in New Delhi. He sold articles to Country Life, itself a conservationist vehicle under Christopher Hussey, gave impassioned broadcasts and wrote polemics for the Architectural Review (fig. 28).126 In an interview with Stamp, Osbert Lancaster remembered Byron at the Review in the 1930s: “he was . . . not a dearly loved character, [but] few could afford to ignore him”.127 And he was famously contrarian. As his friend Nancy Mitford once put it, “Isn’t Robert simply killing? . . . he seems to hate everything, which ordinary people like!”128

125

Stamp acknowledged that his general model for invective was Byron’s How We Celebrate the Coronation.129 It was a wrathful, voluble attack on the institutions that he deemed to be exerting their negative agency over London’s conservation. The polemic followed a huge spate of demolitions of Georgian buildings, culminating in the Adam brothers’ Adelphi Terrace in 1936. The Georgian Group was founded in response in 1937. Stamp was interested in the group’s origins, especially the personalities of its founders, the author and diplomat Lord Derwent, the writer Douglas Goldring, as well as Byron, its first deputy chairman.130 The writer and architectural historian James Lees-Milne was a member of the group from the beginning and enjoyed a lively correspondence with Stamp, whose campaigning he encouraged by advising that “vitriol is the best weapon to use. Robert B. discovered that and used it to wonderful advantage”.131 In the Georgian Group’s infancy, Lees-Milne knew Wilhelmine Harrod (née Cresswell), known as Billa, when she was the organisation’s assistant secretary in the 1930s. She was one of the founders of the Friends of Norwich Churches in 1970 and the founding chair of the Norfolk Churches Trust in 1976, which Mark Girouard saw as “a model for similar organisations all over the country”.132 Stamp was admiring of her achievements and Lees-Milne put him in touch with her in 1982, recalling how “she was . . . my informant re. your intimate friendship with M. Piloti” in Private Eye.133

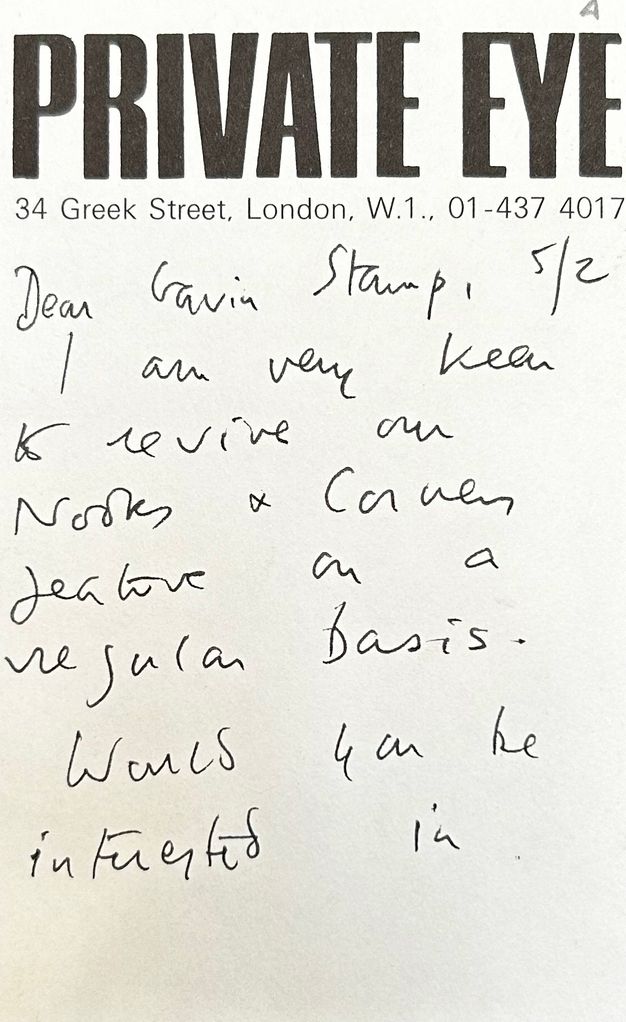

129A clear allusion to Banham’s The New Brutalism, “Nooks and Corners of the New Barbarism” in Private Eye was begun by John Betjeman in May 1971.134 As the magazine’s then editor Richard Ingrams recalled, the column’s object “was to highlight various examples of architectural vandalism of which there was never a shortage”.135 Betjeman’s daughter, Candida Lycett Green, took it over for several years. After a short caesura, Ingrams was keen to revive the column and Betjeman recommended Stamp, who took over in 1978 using the pseudonym “Piloti” (figs. 29a and 29b).136 In that same year, appropriately, Wayne Attoe published his influential Architecture and Critical Imagination, urging critics “to be more political and less politic”—a call, incidentally, met by Stamp over his four decades at Private Eye.137

134

“Nooks and Corners” was a vital place for debating the architectural style wars that were prevalent in the 1970s and the 1980s and an anti-canonical vehicle in which heroes became villains. Stamp sought to give plurality (and accountability) to a discourse where a set of names were thought to be sacrosanct. Above all, he called out sycophancy, especially by exposing what he perceived as the vanity and egotism of the Big Three knighted architects Richard Rogers, James Stirling and Norman Foster. Many architectural monikers were born of Stamp’s wit: Rogers, in anticipation of the Millennium Dome, was dubbed “Labour’s Speer”, while followers of Owen Luder were dubbed “craven Luddites”.138 As so many people were the targets of Stamp’s vitriol, Anthony Rushton, one of the directors of Private Eye, warned him not to express his views too trenchantly at the risk of becoming an architectural history equivalent of the acidic art critic Brian Sewell, adding: “Too much passion is a dangerous thing (how v. English)”.139

138While “Nooks and Corners” has been seen as the mouthpiece of the new architectural Tories, John Martin Robinson described “the purlieus of the Spectator”—in which Stamp, having been invited to join by Alexander Chancellor in 1978, was a regular columnist—as the heart of young fogeyism.140 Stamp could be said to have taken a largely High Tory perspective on politics, remaining an Attlee Welfare State supporter throughout his life, a position not antithetical to conservatism in the 1960s and 1970s. If not a natural conservative, he was far from ever being a socialist or an arch-liberal. Furthermore, as the right began to win out in architecture and society, Stamp moved from the centre right (even extreme right, according to A. N. Wilson) to what might best be described as the centre left, distancing himself increasingly from Conservatism during the course of Margaret Thatcher’s administration.141 The Spectator afforded him the opportunity to voice his project to Thatcher herself, however, in April 1985, as the following exchange records:

140Dear Prime Minister

142It was a very great pleasure and a privilege to meet you last week when you so kindly entertained the Spectator . . . I am afraid I rather went on about Architecture, but it is my subject and I should be sorry to see your Government identified with vandalism just as Lord Stockton [Harold Macmillan] is remembered for the quite unnecessary demolition of the Euston Arch.142

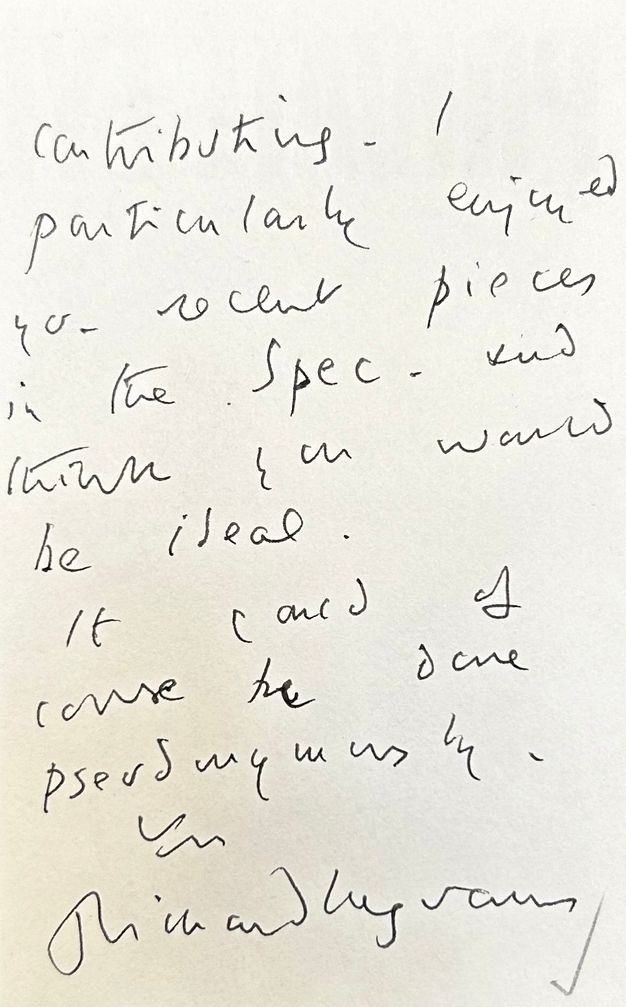

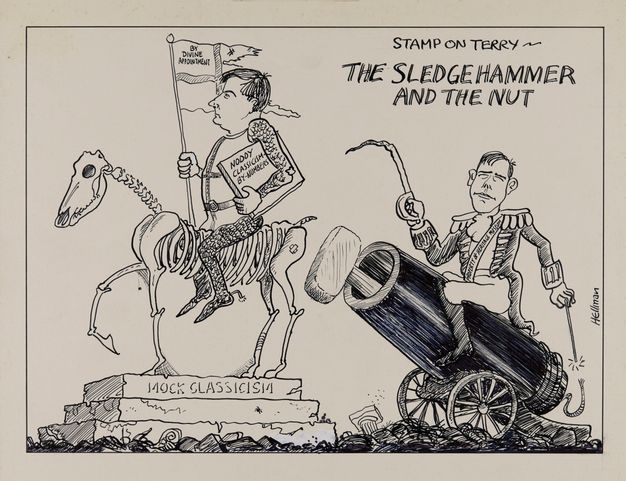

Stamp had met Thatcher in the context of the ongoing Mansion House Square inquiry, a watershed moment for the conservation movement.143 Stamp himself was the subject of visual satire in this capacity in May 1985. Lord Palumbo had failed to gain permission to build a huge tower designed by Mies van der Rohe beside London’s Mansion House. Prince Charles condemned the tower as a “giant glass stump”, a stump that ought, suggested the artist Louis Hellman in his illustration for the Architects’ Journal, to be stumped, as on a cricket ground.144 In the sketch are Marcus Binney, Palumbo and Stamp representing the Thirties Society and Patrick Jenkin, secretary of state for the environment; the late van der Rohe watches proceedings from above. In a further Hellman sketch from about 1988, the stylistic militancy of the moment was dramatically captured via the vitriol Stamp directed towards the classical architect Quinlan Terry (fig. 30). Stamp criticised his “Toytown Palladianism” unendingly, including his Howard Building at Downing College, Cambridge (fig. 31).145 To Stamp, classicism was about innovating the tradition, which he found in Lutyens, Raymond Erith, Francis Johnson, Albert Richardson—and even Donald McMorran and George Whitby, scions of Lutyens, “unsung heroes of an intelligent modern Classicism” whose achievements Stamp helped foreground.146 He reserved huge admiration too for the “inspired strangeness” of Lutyens’s Slovene contemporary Jože Plečnik (fig. 32).147 Yet, in proselytising for his own preferred type of classical revivalism, Stamp was accused by Leon Krier of displaying “the kind of moralistic radicalism that established and maintained Modernism’s intolerant reign”.148

143

Edwin Lutyens and Roderick Gradidge

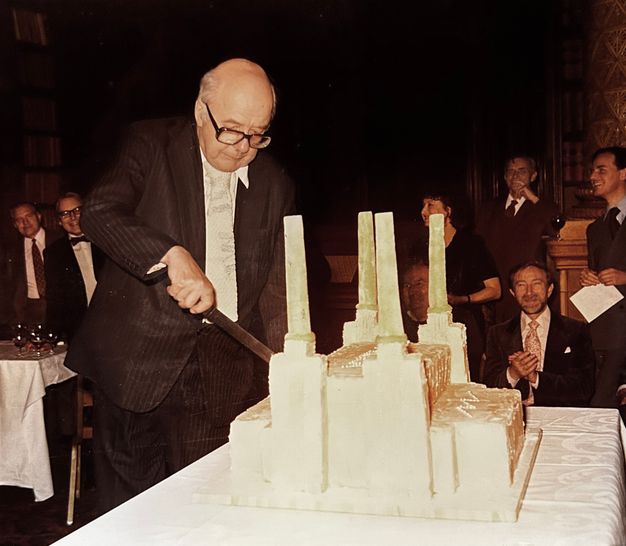

The year after starting at Private Eye, Stamp published Temples of Power (1979), “that most eccentric book . . . on the architecture of electricity”, bringing to fruition his long-term interest in industrial archaeology.149 It contained lithographs on power stations by Stamp’s friend, the artist Glynn Boyd Harte (1948–2003), with a letterpress by Stamp. There was the usual manifesto: Stamp suggested that power stations, often bricky and elegantly mannered, offered a palliative to the “puritanical morality” of functionalism.150 The book was launched at the National Liberal Club with a Battenberg cake made by Fullers’ Bakery, Soho, in the shape of Battersea Power Station (fig. 33). It had pink icing approximating brickwork and solid marzipan chimneys, reinforced by knitting needles.151 Stamp would later be closely associated with conservation campaigns to protect Giles Gilbert Scott’s Battersea and Bankside power stations.152

149

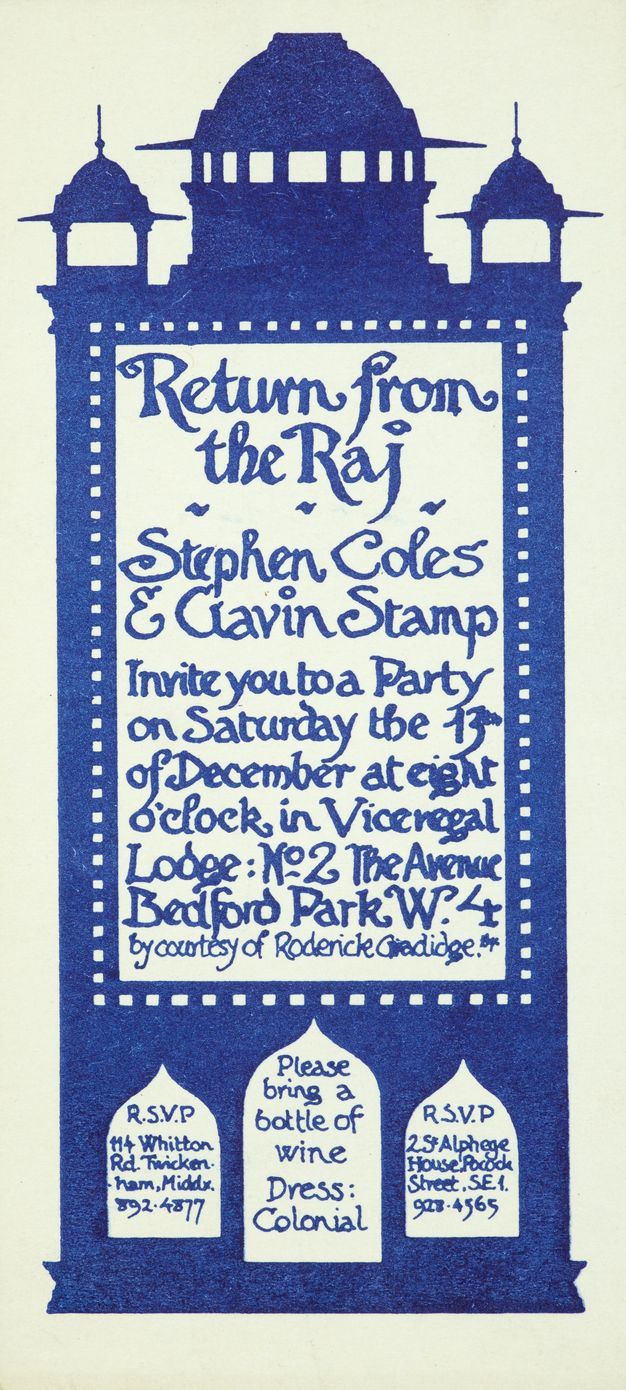

A moral triumph for Stamp’s coterie was achieved with the Lutyens exhibition at the Hayward Gallery (1981–82), designed with neo-Lutyens playfulness by Piers Gough.153 According to Summerson, Stamp’s generation, “having been half-drowned in half-baked Modern ideologies had to ‘discover’ Lutyens”.154 The exhibition met with disapproval from the left, both politically and stylistically, as the conspiratorial gesturing of a resurgent conservative right.155 Rodney Mace saw Lutyens as a representative of a neoconservatism in which “The architect’s role as arbiter of taste, until recently disguised by social democracy, has been re-asserted”.156 Stamp was responsible for the celebratory section on New Delhi, built during the period of the British Raj, which he had first visited in 1975 (fig. 34).157 Although New Delhi was to become, as Mark Crinson put it, “the pre-eminent test case of postcolonial urban studies” three years after the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism, it appears that a postcolonial critical consciousness had barely informed British architectural history.158 However, Stamp reflected in 2002 on the problem of “post-Imperial guilt, which has led to a certain embarrassment about extolling New Delhi”.159

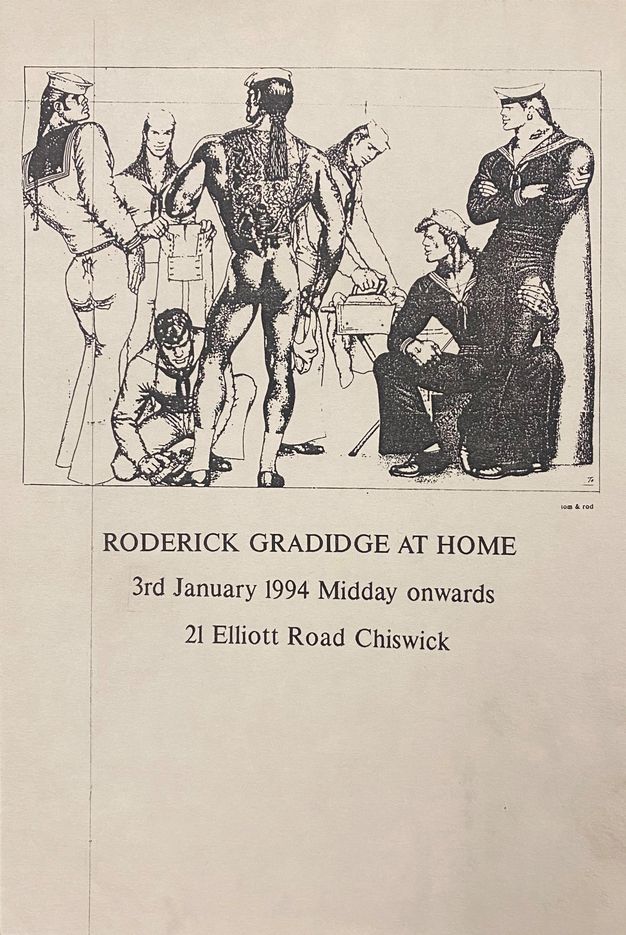

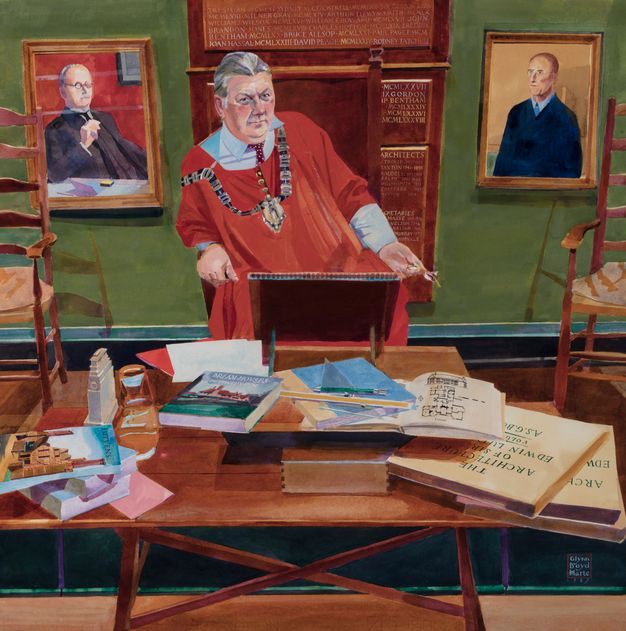

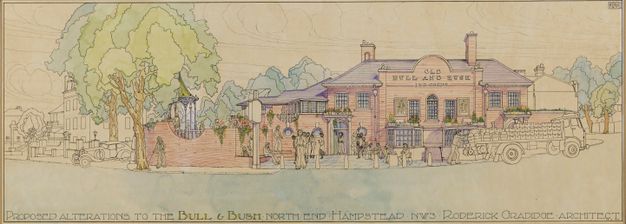

153Stamp’s own interest in Lutyens had been nurtured by his friend the architect Roderick Gradidge (1929–2000), who also set out to combat left-wing tendencies in British architecture and to rescue it from the “Prussian corset” of Pevsner.160 Brought up among the splendours of the Raj—his father was a brigadier stationed in India—Gradidge had an imperious manner and an imperial mindset.161 Flamboyant and openly gay, he wore kilts and was heavily tattooed with designs including the sacred heart and Our Lady and held riotous parties (fig. 35). Gradidge found a sense of belonging at the Art Workers’ Guild, Bloomsbury, which he joined in 1969 and which, as Alan Powers put it, “he saw as a secret cell of anti-modern resistance” (fig. 36).162 “Enthralled by the traditions”, Stamp was also a stalwart of the guild, which he joined in 1973 in his capacity as a graphic artist.163 He worked briefly as a draughtsman in the early 1970s for Gradidge, who was a popular choice for breweries looking to adapt their public houses in historicist styles. Stamp drew a perspective of the Old Bull & Bush public house in Hampstead, London (1923–24), which was being altered by Gradidge (circa 1973) (fig. 37) and made a model for Whitbread’s brewery on Chiswell Street, London.164

160

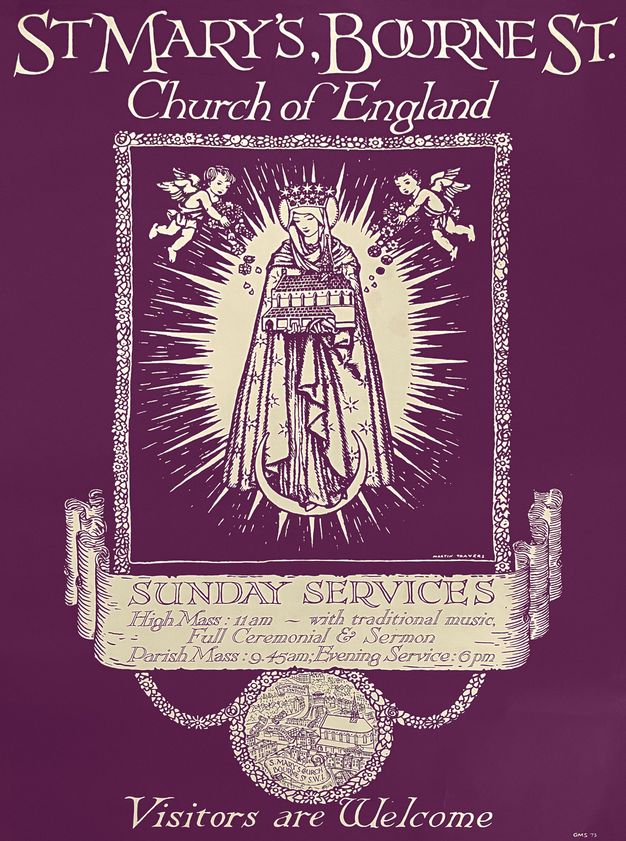

Stamp’s architectural and conservation network interacted closely with an exclusive, homosocial (and often homosexual) world that itself revolved around the High Church. Gradidge introduced Stamp to St Mary’s, Bourne Street, the most Anglo-Catholic church in London then, as now (fig. 38). A former chapel of ease to St Paul’s, Wilton Place (R. J. Withers, 1873–74), it had been extended by Goodhart-Rendel (mostly 1925–28), with fittings classicised by Martin Travers (1921 and 1934).165 Stamp himself lettered the columns to either side of the chancel (1974).166 Mindful of Bourne Street, the High Anglican friends Stamp, Charles Moore and A. N. Wilson co-authored The Church in Crisis, a title that may have deliberately mirrored the seventeenth-century High Tory slogan “church in danger”. It was a critical dismissal of the liberal instincts of the clergy in the Church of England.167 Himself a High Anglican, and perhaps as a result of a deeply ingrained English antipathy, Stamp found the conversions to Roman Catholicism of several friends (including Watkin) and of his wife, Alexandra Artley, dismaying.

165Although Stamp’s formative influences—the lofty and detached Watkin and the more outwardly eccentric and metropolitan Gradidge—were seemingly poles apart, both were gay, chauvinistic and united by their reactionary positions. Stamp’s turn to the past seemingly derived from an inherent conservationist sensibility, whereas Watkin’s outsider status probably had more to do with sex. His whole persona in the 1960s and 1970s, unlike Gradidge’s, was bound up with his repressed sexuality, with which he later made peace.168 Beyond a romantic sensibility, for both Gradidge and Watkin the turn to the past can be seen as the creation of a fantasy to outface an undesirable present. Certainly, Watkin was admiring of Gradidge’s work; he found his remodelling of Bodelwyddan Castle, near St Asaph (1988–89) “brilliantly colourful, imaginative, yet somehow completely authentic”.169 While Stamp and Gradidge’s friendship lasted until the latter’s death, Stamp became increasingly distanced from Watkin and, by the millennium, had complained to Symondson of the “blighting influence” he had exerted over architectural history.170 This was mostly the result of differing views on journalism, modern architecture—and, as we have seen, modern classicism.171

168Reappraising Modernism

In 1982 Stamp married Artley, a journalist who worked for the Architectural Press and who wrote generally liberal social columns for the Thatcherite Spectator and Harper’s & Queen. Following their marriage, the Stamps moved into a late Georgian house at 1 St Chad’s Street, King’s Cross. Their Désordre Britannique at the latter is hyperbolically satirised in Artley’s novella Hoorah for the Filth-Packets!172 A. N. Wilson remembered “St Chad’s Street . . . [as] rather like Catto’s at Oxford, filled with those who would continue to be friends for life”.173

172Stamp once reflected that “the great rule I followed . . . was never ever to meet living architects”.174 Breaking this rule left him vulnerable to doubting his sense of objectivity as a critic, but by doing the opposite he arrived at a more nuanced understanding of modernist architecture, namely his initial re-evaluation of the work of two pioneer émigré architects who helped establish the modern movement in Britain.175 They were, like Stamp, both tall, pugnacious and assertive. Berthold Lubetkin (1901–90) and Ernö Goldfinger (1902–87) had already built reputations in Europe before moving to Britain (Lubetkin in 1931 and Goldfinger in 1934).176

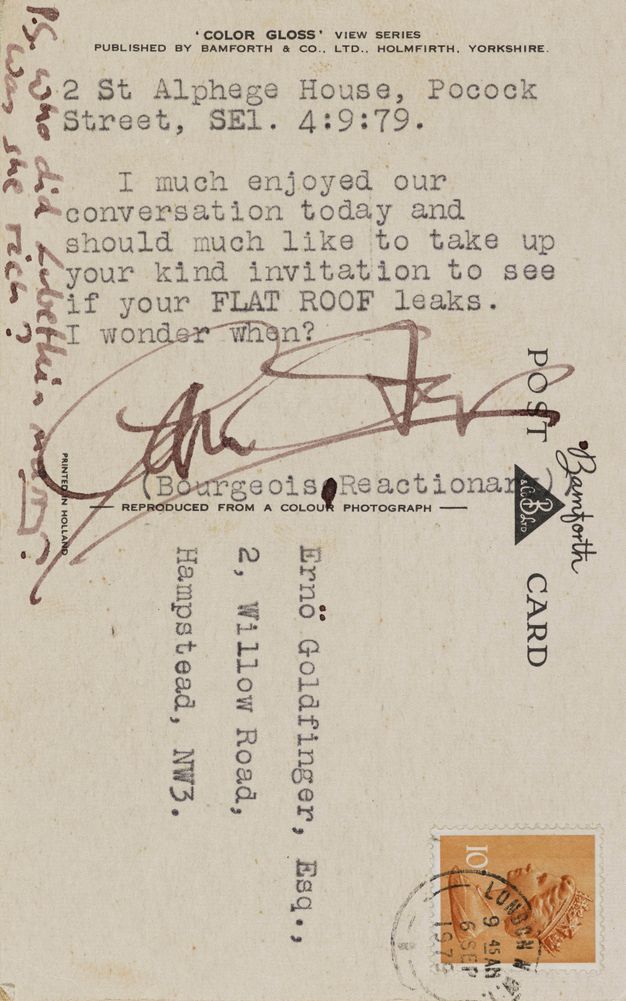

174Stamp recalled to Cathy Courtney in 2000 that, in the late 1960s, “Goldfinger came to represent everything I disliked most about the alien arrogance of the modern movement”.177 “Alien” is reminiscent of Amery and Cruickshank’s The Rape of Britain, a bellicose metaphor to suggest that Britain had been despoiled by foreign interference.178 This view changed when Stamp met Goldfinger at the RIBA Drawings Collection in Portman Square while Stamp was cataloguing the drawings of the Scott dynasty.179 The Drawings Collection under the helm of John Harris (between 1970 and 1986) was another key centre for architectural history, which Simon Swynfen Jervis recalled as being “informal, epicurean and noisy . . . a convivial and cosmopolitan meeting place and gossip-shop”.180 Stamp himself remembered the collection as “a great centre of activity and scholarship . . . [even] the kitchen was a . . . social event”.181 Goldfinger arranged to deposit his archive at the RIBA, within which can now be found a handful of exchanges from Stamp to Goldfinger. In the earliest, signed “Bourgeois Reactionary”, in September 1979, Stamp desired “to take up your kind invitation to see if your flat roof leaks” at his home at Willow Road, Hampstead (fig. 39).182 Stamp’s critical interest in Goldfinger came to fruition in the 1983 exhibition at the AA curated by Stamp and James Dunnett. Stamp reflected on it in a letter to Goldfinger in May 1983, addressed to him at the “Anglo-Soviet Friendship House”: “I do hope you will be pleased with the catalogue [containing] . . . a neo-Fascist piece by me and a Stalinist eulogy from James. It has all been very enjoyable and an education for me”.183

177

Stamp corresponded with Lubetkin at least as early as 1983, opening his letter to him with a caveat that seemed necessary: “As I live within ten minutes’ walk of the Finsbury Health Centre, Holford Square [Bevin Court] and Priory Green [now Priory Heights], I certainly cannot, and would not dismiss your work”.184 He invited Lubetkin to lecture at the Architectural Association the following autumn, but Lubetkin, who shared much of Stamp’s own sense of estrangement with contemporary architecture, declined the invitation: “In spite of the glorious past of this institution [the AA], I consider it now as a hornet’s nest, a citadel of international headquarters of terrorists of art. They are dispensing zany, goofy gobbledigook!”185 Stamp would later reassure him that, despite his association with the AA, he was himself “a huge-eared and senile reactionary”.186

184Stamp interviewed Lubetkin in 1987 at his Clifton home, and the interview was published in the Architects’ Journal.187 In the correspondence that followed, Stamp discussed his admiration for “the strange romance . . . beauty and cleverness” of Lubetkin’s work at Dudley Zoo, especially the Penguin Pool, which had been demolished in 1979.188 He also discussed the latter with Summerson, who quipped to Stamp: “The Penguins have, I suppose, been reading David Watkin—just their cup of cocoa”.189 Stamp’s equal admiration for Lubetkin’s zoo architecture in London was aided by visits to London Zoo with his young daughter Agnes (and later Cecilia). Stamp reflected with jocular regret to Lubetkin, after visiting the Penguin Pool (Lubetkin and Tecton, 1934) in 1987, that “It is now quite fortified . . . [and] quite difficult for children and penguins to meet each other . . . I have to lift up my daughter [over the parapet]”.190

187Stamp had built his journalistic reputation by attacking modernist architects, but they were no longer self-deceived Hampstead trendies as caricatured by Osbert Lancaster but part of a premise that looked increasingly valid, even commendable.191 He also began to drop his use of “Marxist” as a term of abuse, even though it was seldom used literally.192 If exposure to the architects in person led to a chink in his armour, Stamp was now not too far away from subscribing to the tradition of understanding architecture according to the Geistesgeschichte and Zeitgeist. In a profile of him at his 1827 home at St Chad’s Street in Lees-Milne and Moore’s The Englishman’s Room, Stamp referred to the wide popularity of the Regency style in which he and his wife had fashioned it, jokingly admitting that, “try as we will, we are all victims of fashion and prisoners of the Zeitgeist”.193 Yet, for all of Stamp’s acceptance of the Zeitgeist, he championed those with the independence of spirit to give it “a bold slap in the face”.194

191A Hack at the Mack

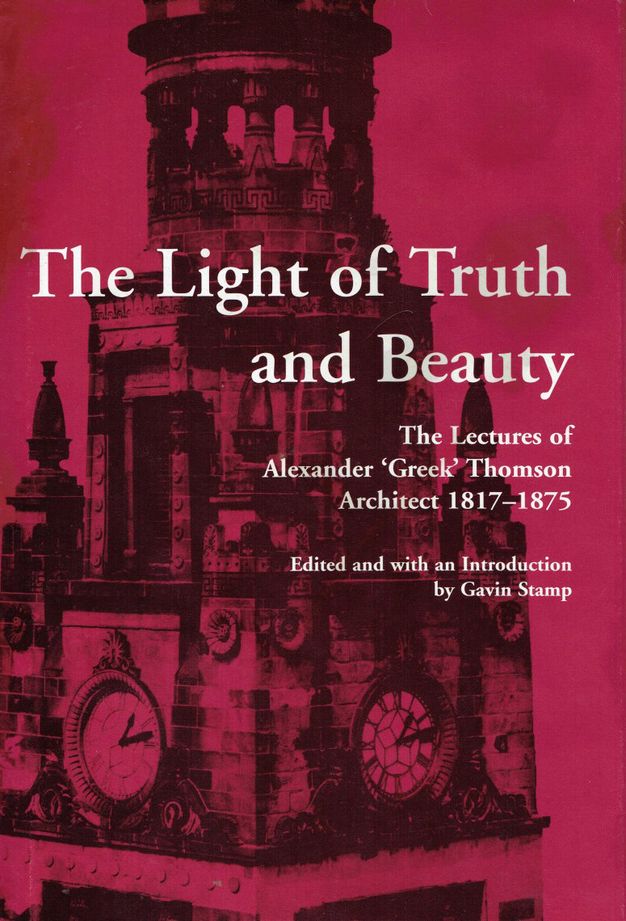

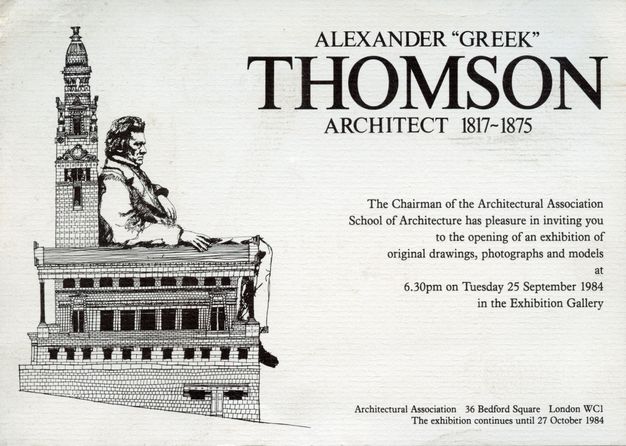

“Well, well!”, wrote Summerson to Stamp on 2 May 1990, “So you are installed at the Mackintosh School and thinking of living in Thomson’s house, a really strong combination of seats”.195 Inveigled by the architectural historian and lecturer James Macaulay (1934–2022), Stamp took up an academic position as a lecturer at the Mackintosh School of Architecture that year; he was later senior lecturer (and honorary reader) from 1999, head of history between 1997 and 2003, and personal professor in 2003.196 He justified the move to the Mack to Boyarsky at the AA: “This rival organisation has offered me a proper job and, being rather sick of journalism, I have taken it”.197 In Glasgow, Stamp lived in Néo Grec splendour at 1 Moray Place, Strathbungo, built by Alexander “Greek” Thomson (1817–75), a Glaswegian Scot and Presbyterian architect, who strove to keep classicism going in Scotland in the midst of the Gothic Revival (fig. 40). Thomson developed, from the mid-nineteenth century, a distinctive abstract Grecian style, particularly influenced by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Stamp helped redress the balance between the reputations of Thomson and of Charles Rennie Mackintosh in shaping Glasgow. To help retrieve Thomson, Stamp republished and edited the architect’s intellectual literature; founded the Alexander Thomson Society in 1991; curated several exhibitions; and co-made a documentary film (figs. 41 and 42).198 His efforts also likely inspired CZWG Architects’ hyperbolic riff on Thomson in their office building in Glasgow’s Cochrane Square.

195

Stamp became interested in locating and celebrating Scotland’s own vigorous architectural traditions, from nineteenth-century neoclassicism (principally Thomson) to Arts and Crafts (principally Robert Weir Schultz) to modernism (principally the post-war work of Gillespie, Kidd and Coia), the last nurtured through his relationship with the architects Andy Macmillan (1928–2014) and Isi Metzstein (1928–2012) who were on the staff at the Mack. “The image of a sober, serious English gentleman in amongst Andy Macmillan’s whiskey-sodden Glaswegian scene” seemed incongruous to Boyarsky, but Stamp had crossed the frontier into modernism in a new way.199 He saw Gillespie, Kidd and Coia’s seminary in Cardross (1958–66), for example, as “the supreme manifestation of the enlightened artistic patronage that characterised the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Glasgow in the Fifties and Sixties” (fig. 43).200

199

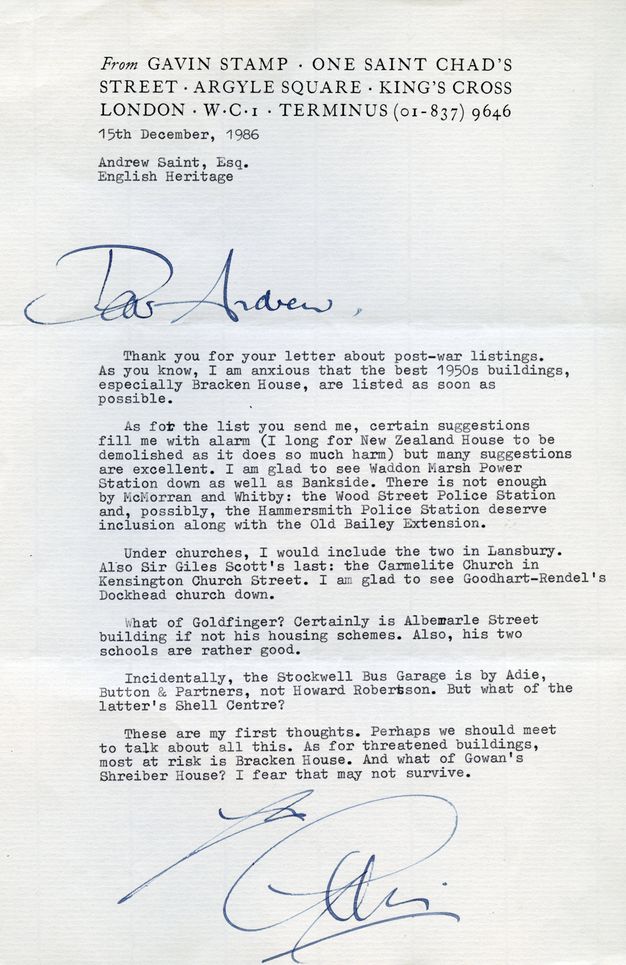

Stamp’s journalism and activism continued alongside his teaching and research. In May 1991, as “Piloti”, for instance, he looked back on the “barbarous” impact of 1980s neoliberalism in which “the Thatcher years [sought] a chimera of efficiency”.201 During Thatcher’s administration, the appetite for listing more interwar, and then post-war, buildings had grown following the pre-emptive destruction of the Firestone Factory, Brentford, London (Wallis, Gilbert & Partners, 1928) in 1979. This helped reveal the extreme vulnerability of twentieth-century architecture, resulting in the Heseltine Resurvey. Stamp became a key player in shaping the protection of post-war buildings as a result of his involvement (1992–2003) in English Heritage’s Post-War Listing Steering Group, established in 1992 (fig. 44).202 At this time, he also reflected on the theme of changing his mind about modernism in the Spectator:

201203In the cause of objectivity [. . . and] cursed by that historical sense that makes me see the point of things I once loathed . . . I now find myself almost liking the clinical, Classical purity of late Mies [van der Rohe]. But if I ever start defending St Thomas’s Hospital, I should be put down.203

Stamp’s oeuvre as a scholar remained varied and industrious into the new millennium. At the Mack he developed his work on interwar architecture, Lutyens, the Scott dynasty and Scottish architecture, but perhaps the total Stamp, the activist-scholar, was not an easy fit with academic culture. Although he published some twenty-seven books and exhibition catalogues (twelve while at the Mack) and numerous peer-reviewed articles over his lifetime, his wider-reaching contribution to architectural history through popular journalism and criticism was less likely to be acknowledged by the Academy. This included bringing his enthusiasms to a much wider audience as a television presenter for the BBC, including in episodes of One Foot in the Past, especially on Bankside Power Station in 1993 and on Thomson’s St Vincent Street Church, Glasgow, in 1994. His rhetorical strategies are revealed in the annotated script of the latter, in which Stamp desired to open with “a vitriolic piece to camera”, with opening shots of the church accompanied by music from Beethoven’s Fidelio (figs. 45a and 45b).206 In any case, Andrew Sanders remembered Stamp as being snooty about academics before his own appointment and that “Gavin wished to be a public figure, which meant journalism”.207 Or, as Alan Powers grimly but tellingly put it, “Gavin was too much of a communicator to be an academic”.208 Stamp might well fit the remit of one of Stefan Collini’s biographical subjects in Common Reading, figures who “attempted to sail a course between the rocks of journalistic superficiality and academic unreadability”.209

206

This sense of academic displacement brings to mind Thomas Weaver’s argument that “the universally accepted Humboldt method [in academia] has had a detrimental effect on the way we write architecture, because in its promotion of science over art and its consistent championing of research, it devolves out of academicism the responsibility to be literary or writerly”.210 Stamp’s writing was writerly, his primary tool to engender pleasure and appreciation, to help shape a public discourse and to ameliorate a polarised architectural culture. He also used words to stand up for a visual rather than purely literary architectural culture, in line with Roger Scruton’s thesis in The Aesthetics of Architecture.211 A case in point is his critique of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates’ National Gallery extension (1991). Although Stamp admired Robert Venturi’s contribution to the eclecticism of contemporary practice through his writings, as well as his championing of Lutyens, he thought that the National Gallery building was contrived in its deliberate creation of complexity and contradiction:212 “There is a world of difference”, he argued, “between a mannerism or innovation which enriches an architectural system, or discipline, and a camp joke which undermines and trivialises it”. In short, “great buildings are compositions which are immediately Comprehensible [sic] visually”.213

210In 2003, after thirteen years, Stamp decided to leave Glasgow. He briefly (and unsuccessfully) sought an alternative academic appointment (including at the University of York) and applied (also unsuccessfully) to follow in Summerson’s footsteps as curator of the Sir John Soane’s Museum. His return to London, this time to a mansion flat in Forest Hill, marked a return to full-time journalism. He had separated from Artley in Glasgow, and the move to London was in part prompted by his relationship with Rosemary Hill, whom he married in 2014.

Stamp found a new opportunity to continue his campaign through longer-form journalism as an often curmudgeonly architectural columnist for Apollo magazine from April 2004, which he continued until his death. A selection of articles were anthologised as Anti-Ugly.214 Although thematically wide-ranging, Stamp’s column continued to dispel the “uncritical reverence” of modernism.215 Furthermore, in spite of the softening of his Peterhouse ideas in the 1980s, many of Stamp’s late opinions can hardly be said to have been leftist. An example is Stamp’s defence in 2013, on aesthetic grounds, of the architect Herbert Baker’s Rhodes House, Oxford, a memorial to the diamond mogul, imperialist and racist Cecil Rhodes and home of the Rhodes trustees, whose reputation, Stamp argued, “circumstances [had recently] contrived to diminish”.216 The millennium brought further work on television including Pevsner’s Cities (2005–6) and Gavin Stamp’s Orient Express (2007) for Channel 5 (fig. 46). Stamp also furthered the theme of architectural loss, for example in Lost Victorian Britain, and brought his interest in the memorial architecture of the Great War to a poignant conclusion in The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.217

214

Stamp’s hitherto unfinished opus Interwar: British Architecture 1919–1939 has been published posthumously, bringing to completion his attempt to grapple with and contextualise the stylistic pluralism and “contradictory tendencies” of the period, a subject that occupied his whole working life.218 A further key area of research and writing for Stamp in the years before his death was the Anti-Ugly Action Group, which in the 1950s experimented with inventive forms of architectural criticism to provoke and encourage debate about the style and quality of British architecture.219 In spirit if not in taste, they were the heroic forerunners of Stamp’s lifelong project.

218Conclusion

Epitomising the architectural historian as activist-scholar, Stamp contributed to a substantial growth of new knowledge, heritage consciousness and informed debate. In the process, his diverse outputs were significant discourse makers that impacted the way architecture was talked about, perceived, discussed, taught, preserved and ultimately canonised.

Stamp subscribed to “an ongoing creative process of environmental improvement”, seeing architecture and conservation as tools to help vitalise people and revitalise cities.220 As Charles Moore put it, Stamp had “a keen sense of how what we build can capture or obliterate what is good about our culture . . . [and] how the public realm can exalt or degrade the life of each citizen”.221 Championing aestheticism over the (especially economic) realities of construction and practice, Stamp’s focus was generally on form, including a belief (akin to the Welsh architectural critic Arthur Trystan Edwards’s) in good and bad “manners” in architecture, or even in “the secret of beauty . . . that tectonic Holy Grail”.222 He wanted beauty to reign around him.223 And, although he occasionally made an ecological case for protecting a building, his oeuvre cumulatively stressed the importance of psychogeography and cultural sustainability in tune with Wilfried Wang’s manifesto on Architectural Criticism in the Twenty-First Century: “Sustainability is not reducible to just a technical question; it must also provide enduring aesthetic delight in order to be organically rooted in a given culture”.224

220Stamp’s project was, furthermore, a cultural critique against architectural obsolescence in favour of universal and timeless values. His academic crushes epitomised these: Lutyens was the author of “works of transcendent humanity and originality within the Western tradition”; Thomson argued for “timeless laws by which tradition could come to terms with contemporary conditions [and] for a rational resonant modern architecture beyond fashion and sentimental associations”; and Scott junior, who like others of his generation rejected self-conscious novelty, was concerned with stasis over contemporary “development”, “an ideal informed by precedent yet timeless, transcending history while being inescapably part of it”.225

225While his interests broadened and shifted over the course of his life, his means and the goal remained to the end. Though seldom given to caprice or compromise, Stamp was also quite capable of changing his mind, including at the very end of his life.226 Attending Guy’s Hospital, London, for cancer treatment in 2017, in a new building by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, a practice he famously loathed, he found “a sympathetic building . . . that works, and has, I think, made both staff and patients happier—as good architecture should”.227

226Acknowledgements

That Gavin Stamp left a mark on so many, and that he spread his affections so widely, quickly became apparent when I began to work on this project as the first Library and Archives Fellow of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. The support of members of Stamp’s family—Alexandra Artley, Rosemary Hill, Agnes Stamp, Cecilia Stamp, and Gerard Stamp—has been invaluable. I have benefited vastly from conversations and correspondence with many of Stamp’s friends, including Mosette Broderick, Dan Cruickshank, Anthony Geraghty, Peter Howell, Ken Powell, Alan Powers, John Martin Robinson, Andrew Saint, Andrew Sanders, Nicholas Taylor and A. N. Wilson. Further thanks are due to those who kindly answered queries and/or helped me access materials: Susie Barson, Gergely Battha-Pajor, Ed Bottoms, Eleanor Dickens, Paul Doyle, Leigh Milsom Fowler, Oli Marshall, Tom Mason, Anna McNally, Janette Ray, Kathy Redington, Teresa Sladen, and William Terrier. At the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, I wish to thank Charlotte Brunskill, Hannah Jones, Martin Myrone, and Sarah Victoria Turner, and at British Art Studies I extend my thanks to Baillie Card, Chloë Julius, Maisoon Rehani, and my anonymous readers.

About the author

-

Dr Joshua Mardell, FSA, is an architectural historian. He is a Tutor (Research) at the Royal College of Art and a co-editor of the Journal of Architecture.

Footnotes

-

1

Gavin Stamp interviewed by Niamh Dillon, 18 December 2017, British Library Sound Archive, London, National Life Stories Collection. ↩︎

-

2

Gavin Stamp, “Neo-Tudor and Its Enemies”, Architectural History 49 (2016), 2. As he put it himself, Stamp “was brought up in a Tudor bungalow on the Orpington By-Pass” in Petts Wood (Gavin Stamp, “Britain in the Thirties: AD Profiles 24”, special issue, Architectural Design 49, nos. 10–11 (1979), 25), before moving to Sandiland Crescent, Hayes, when he was three (Gerard Stamp, email to author, 1 June 2023). ↩︎

-

3

Stamp interviewed by Dillon. ↩︎

-

4

Gavin Stamp, “Nooks and Corners”, Private Eye 731 (22 December 1989): 9. ↩︎

-

5

Stamp, “Neo-Tudor and Its Enemies”. ↩︎

-

6

Ibid., 3. ↩︎

-

7

Gavin Stamp, “Dorothy Stroud”, Daily Telegraph, 15 January 1998, 25. ↩︎

-

8

Gerard Stamp, conversation with author, 2 March 2024. ↩︎

-

9

Oliver and Clara Rich, Stamp’s maternal grandfather and grandmother, were members of the Bristol Socialist Party. Oliver Rich was a buyer for a clothing company that supplied First World War uniforms. He died of influenza in 1932 when Norah was only fourteen, which meant she had to leave school and go out to work (Gerard Stamp, email to author, 8 January 2023). ↩︎

-

10

There are numerous obituaries of Stamp in addition to Alan Powers’s entry on Stamp in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Alan Powers, “Stamp, Gavin Mark (1948–2017)” (2021), DOI:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000380357). In following a largely anecdotal approach, I have been informed by Joseph Epstein, Gossip: The Untrivial Pursuit (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), and Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory, vol. 1, Past and Present in Contemporary Culture (London: Verso, 1994). ↩︎

-

11

Timothy Brittain-Catlin, “The Success of Failure”, lecture delivered at the Annual Colloquium of Doctoral Students of the Institute of Technology and the History and Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich, 17–18 November 2016. Conversely, Sarah Whiting has raised fears that the digital revolution has given the discipline too many voices (Sarah Whiting, “Possibilitarianism”, Log, no. 29 (Fall 2013): 153–59). This is mirrored by Peter Kelly, writing on the shift of architectural criticism towards non-traditional media and arguing that there is a dearth of critical writing (Peter Kelly, “The New Establishment”, Blueprint, no. 297 (December 2010): 60–64. ↩︎

-

12

Adrian Forty, “Architectural History Research and the Universities in the UK”, Rassegna di Architettura e Urbanistica 139 (2013): 7. ↩︎

-

13

Stamp was a founding member of the Lutyens Trust, the Alexander Thomson Society and the Thirties Society. ↩︎

-

14

David Watkin, The Rise of Architectural History (London: Architectural Press, 1980), 183–90. Watkin described conservation advocacy as a “recent tendency” – and yet there were, of course, considerable forebears. ↩︎

-

15

The archival evidence for the early work is also stronger, owing to its physical nature. I was unable to access some more recent parts of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (PMC) archive, which were closed for consultation under the conditions of General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). ↩︎

-

16

Alexandra Artley and John Martin Robinson, The New Georgian Handbook (London: Ebury Press, 1985), 7. ↩︎

-

17

Anthony Geraghty, “Gavin Stamp”, Architectural Historian, no. 6 (February 2018): 20–21. ↩︎

-

18

Anthony Geraghty, conversation with author, 3 February 2024. ↩︎

-

19

Hélène Lipstadt, “Letter from London”, Skyline: The Architecture and Design Review, May 1982, 8. ↩︎

-

20

Ian Jack, “Gavin Stamp Obituary”, Guardian, 7 January 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jan/07/gavin-stamp-obituary. ↩︎

-

21

Ian Hislop, quoted in Richard Waite, “Tributes Pour in for ‘Elegant and Opinionated’ Gavin Stamp”, Architects’ Journal 245 (11 January 2018): 7. ↩︎

-

22

Lynne Walker, “‘The Greatest Century’: Pevsner, Victorian Architecture and the Lay Public”, in Reassessing Nikolaus Pevsner, ed. Peter Draper (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 129–48. See also Peter Mandler, “John Summerson 1904–1992: The Architectural Critic and the Quest for the Modern”, in After the Victorians, ed. Susan Pedersen and Peter Mandler (London: Routledge, 1994), 229. ↩︎

-

23

Gavin Stamp, The Changing Metropolis: The Earliest Photographs of London (London: Viking, 1984), 9. ↩︎

-

24

Gavin Stamp, “Nooks and Corners”, Private Eye 1053 (8 May 2002): 9. ↩︎

-

25

James Marston Fitch, “Architectural Criticism—Trapped in Its Own Metaphysics”, Journal of Architectural Education 19, no. 4 (1976): 3. ↩︎

-

26

Joan Ockman, “Slashed”, e-flux Architecture, October 2017, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/history-theory/159236/slashed. ↩︎

-

27