“Your Most Obedient and Faithful Servant”

Issue 26 – May 2025

Download Contents

“Your Most Obedient and Faithful Servant”: Peregrine Tyam and the Representation of Black Sitters in Early Modern British Portraiture

By Hannah Lee

In 1692 a young Black boy known as Peregrine Tyam was painted alongside Mary Lawley in a portrait commissioned by her husband, John Verney, to mark their marriage. It is very likely that Peregrine Tyam was enslaved, as indicated by the silver collar he wears around his neck in the picture. In 1689 he was baptised at around six years of age on the Verney family estate at Middle Claydon church, and he lived with John Verney until his death in 1707. By the end of the seventeenth century, the depiction of a Black attendant alongside a White sitter was a fashionable format in British portraiture, directly reflecting Britain’s rise to dominance in the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people and the growing number of enslaved people living and working in elite British households. The portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley is a rare example of a picture of this type where the identity of the Black sitter is known and is accompanied by a body of documentary evidence that allows for the partial reconstruction of their biography. In this case, it includes a letter written by Tyam himself that provides an even rarer glimpse into the experience of a young Black man in early modern England in his own voice. The depiction of Tyam in the portrait served a symbolic purpose, sending a message to the viewer about the Verney family’s status and John Verney’s involvement with the Royal African Company. However, this article argues that Tyam’s portrait should be understood as more than a symbolic stock representation. Analysed alongside documentary sources from the Verney family archive, it provides us with an insight into Tyam’s life with the family. The portrait is evidence that in some cases it is possible to restore the identities of the numerous unknown Black sitters in early modern British portraits, along with their voices and a sense of their experiences.

Introduction

The inventory of Claydon House in Buckinghamshire, made in 1740, lists a portrait hanging in the drawing room as “John Fermanaghs second Lady by Lentall half length”.1 The portrait depicts Mary Lawley, the second wife of John Verney, who would later become the 1st Viscount Fermanagh. The document does not mention her by name, and also fails to note that there is a second figure in the portrait. Standing behind the right shoulder of Mary Lawley is a young Black boy.2 On 6 October 1689, he was baptised at Middle Claydon church with the name Peregrine Tyam (figs. 1–2). He was then around six years old and is described in the parish register as coming from “Guinea”, a term that at the time was often used as a general descriptor of West Africa.3 The name Peregrine was most likely selected by John Verney of Claydon House, whose name takes the place usually allotted to a parent in such registers. The portrait of Peregrine Tyam is an important case study in examining the representation of Black sitters in early modern British portraiture. It is unique in that the identity of the sitters and the provenance of the picture are both known, along with a significant body of surviving documentary evidence from letters and account books that provides an insight into Peregrine’s life as part of John Verney’s household. Most importantly, these documents include a letter written by Peregrine himself, recovering a sense of his voice and agency.

1

John Verney was the second son of Sir Ralph Verney, 1st Baronet of Middle Claydon in Buckinghamshire. Following the deaths of his elder brother and nephew, he inherited his father’s title in 1696. As a young man John established himself as a merchant, spending time in Aleppo before returning to London to continue his career. Like his father before him, he was a prolific letter writer and record keeper, and his extensive correspondence with family members, social and professional contacts, servants, and tradespeople survives in the Verney family archive today, including the letter written to him by Peregrine Tyam in March 1699.

Peregrine’s letter is a unique historical source, providing a brief glimpse into the life of the young boy in the portrait in his own words. In contrast to the rarity of such letters, by the time of the painting in which he is depicted, the inclusion of Black attendants in portraits had become a fashionable trope in British visual culture. Susan Amussen notes the survival of over seventy portraits of this type dating from the beginning of the seventeenth century and the first decade of the eighteenth century.4

4This directly corresponded to the period when Britain rose to dominance in the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people, while the gentry and mercantile classes brought enslaved African people to Britain to live and work in their homes. Between 1651 and 1675 English ships carried an estimated 25,731 enslaved people from the coast of West Africa to the Americas, a figure that then increased dramatically to 272,200 between 1676 and 1700.5 Both David Bindman and Catherine Molineux have highlighted that the origins of the attendant portrait derived from European court portraiture of the preceding centuries. David Bindman notes the importance of the restoration of Charles II to the throne, and the re-establishment of closer connections to European courts where the presence of Black servants and enslaved people, and their inclusion in portraits, became increasingly fashionable.6 Molineux cites the influence of portraits by Titian, with the compositional format then arriving in Britain through the work of the Netherlandish painters Rubens and Van Dyck.7 Between 1675 and 1688, Richard Tompson produced a mezzotint of Titian’s portrait of Laura Dianti, which shows her standing with her hand on the shoulder of a small Black boy, contributing to the circulation of this composition in Britain (fig. 3).8

5

Clearly the inclusion of Black figures in such portraits served a symbolic purpose, and it is this symbolism on which art historical analysis has largely focused. Kim Hall has argued that the presence of these individuals in British portraits of this period highlights that, even before Britain had become dominant in the Atlantic slave trade, Black people “played an important role in the symbolic economy of elite culture”.9 Scholars have explored how these figures highlighted the wealth of the White sitters and their involvement in flourishing colonial trade, acting as visual signifiers of the consumption of and investment in “exotic” commodities such as sugar, tobacco, and coffee.10

9Scholars have also focused on the dynamic between the sitters represented in these portraits, paying particular attention to the visual relationship between young Black attendants and White female sitters. Hall argues that the presence of an attendant with black skin “becomes a key signifier in such portraits: associated with wealth and luxury, it is the necessary element for the fetishisation of white skin, the ‘white mask’ of aristocratic identity”.11 Examination of these ideas is not limited to seventeenth-century British portraits of this type, and forms an important component in the analysis of earlier European precedents and later eighteenth-century examples. In her analysis of the representation of the attendant in Van Dyck’s 1623 portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, Ana Howie notes that “Elena’s beauty emanates light … Paradoxically the shade of the parasol falls upon the dark complexion of her attendant who becomes her shadow, a pictorial counterpart to her luminous beauty”.12 In a discussion of a portrait of Mary Wortley Montagu and an unknown attendant dating to around 1745 and attributed to Jonathan Richardson, Marcia Pointon describes how the young man in the portrait “serves as the ideal complement to Montagu: situated in the shadow behind her, the red of his coat and stockings setting off the brilliance of her clothing, his dark skin contrasting with her faultless white complexion, forming a visual trope in which a white woman is empowered in colonial and sexual terms”.13

11Beyond the analysis of the symbolic presence of Black individuals in British portraiture of this period, there has also been a growing number of research projects focused on identifying the unknown sitters represented. Only a handful of Black sitters who are depicted in these portraits have been identified, and most of these examples date to later in the eighteenth century. Recent research undertaken by the Yale Center for British Art and the West Sussex Record Office has recovered the identity of Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas, who is depicted alongside Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Harrington, in a portrait of 1782 by Joshua Reynolds.14 The identification of Marcus Thomas’s name in Reynold’s sitter book is particularly groundbreaking and an important milestone for research into portraits of Black sitters in early modern British art (fig. 4).

14

To date, the portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley is one of the earliest British easel portraits to depict a person of colour where the identity of the individual is clear.15 The appearance of a young person of colour in a British portrait of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries does not always mean that the child was a member of the commissioning sitter’s household. Such was the popularity of this type of composition that there are examples of artists using the likeness of a child as a template, with the same individual then appearing in a number of different portraits. Catherine Molineux highlights the example of a young Indian boy who appears in an almost identical kneeling pose in Peter Lely’s portraits of both Elizabeth Cooper and Charlotte Fitzroy. This method seems to have also been adopted by Peter Lely’s assistant Willem Wissing in his own works. Likenesses of the same child appear in at least three of Wissing’s portraits of the 1680s (fig. 5–8).16

15

Catherine Molineux argues that these portraits were “staged images that cannot be read as direct transcripts of black experiences of service”.17 David Bindman notes that, “while some of the black children represented in portraits did actually exist, they essentially belonged to a world of spectacle and fantasy, whatever the mundanity of their household duties”.18 The reuse of likenesses by artists across multiple different portraits supports these arguments to an extent, emphasising the objectification and subordination of these figures as tools of symbolic representation. Despite these images being reused, it should be remembered that they were probably originally drawn from the likenesses of real individuals who might have been living as enslaved servants in one of the homes of the people alongside whom they were depicted. Clearly the Black people depicted in these portraits were included for a symbolic purpose, but it does not mean that they were fictive or that the manner in which they were portrayed bore little relation to their lived experiences.

17Peregrine Tyam’s presence in the Claydon portrait was clearly a deliberate choice by John Verney to communicate something about his status. However, evidence from the letters and household account books from the Verney archive show that Tyam’s portrait tells us more than the typically symbolic stock depictions of Black sitters at the time. The picture is evidence that it is possible in some cases to restore the identities of these individuals and a sense of their experiences and voices. Furthermore, such research frequently uncovers the identities of other erased individuals, expanding our understanding of Black lives in early modern Britain.

Commissioning the Picture: The Possessions of John Verney

In step with many families of their social class, and like generations of their own family before them, the Verneys of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries commissioned portraits of themselves from some of the most famous painters of the time. The Claydon inventory of 1740 lists family portraits by Anthony Van Dyck and Peter Lely, and later portraits by Godfrey Kneller, who lived close to the Verney family in Covent Garden.19 John Verney’s accounts for October 1707 included a payment of £6 9s. for a portrait of his son Ralph Verney by the artist Enoch Seeman the elder.20

19The family also engaged the services of a number of different London-based painters whose works are less well known today. Lenthall, to whom the portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley is attributed, falls into this latter category.21 Frances Parthenope Verney, the author of Memoirs of the Verney Family, published between 1892 and 1899, was dismissive of the quality of the portrait. Describing the contents of the 1740 inventory, she noted that “there are new pictures of my Lord and Lady, but, alas! By Walker and Lenthall, instead of the Vandycks and Cornelius Johnson of the previous generation”.22

21A portrait of Elizabeth Baker, John Verney’s third wife, has also been attributed to Lenthall, but very little is known about the artist, including his first name (fig. 9). No painter with this surname appears in the membership records of the Painter-Stainers’ Company or the register of apprenticeship bindings.23 His name does appear, however, in a document discussing the commission of a portrait of Queen Anne for the London Guildhall in March 1702, where he seems to have been one of the artists considered for the task. The Court of Aldermen reported that “Sr Godfrey Kneller Mr Closterman Mr Richardson Mr Lentall and Mr Lely” should be among those to prepare sketches or designs for the portrait to be put up for consideration.24 While the competition for the commission was eventually won by John Closterman, Lenthall’s inclusion in this list alongside more high-profile artists shows that, although his name and oeuvre are little known today, he was operating within the same spheres. Waterhouse describes Lenthall as a “London portrait painter of some repute” and the two portraits at Claydon as “in an individual and slightly vulgar Knellerish style”.25

23

Specific details of the commission of the portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley remain unknown, but it has generally been accepted that it was painted to mark the marriage of John Verney and Mary Lawley in the summer of 1692. The style of dress and hair worn by Mary would support this date, along with the age of Peregrine who would have been about nine years old at this point.

No explicit mention of the commission of this portrait has yet been found in the Verney papers, but a reference to another family portrait commission may shed some light on when it was produced. On 10 August 1692, in the month following his marriage to Mary Lawley at Westminster Abbey, John Verney wrote to Ralph Palmer (the father of his late first wife, Elizabeth) that “Mr Earle the painter staies out of towne until Michaelmass soe that Ile wait some other convenience to have Miss Bettys picture”.26 The Betty mentioned here refers to his daughter Elizabeth, and it is clear that this was a moment when John Verney was looking to commission family portraits. In a second letter to his father, Ralph Verney, on 30 August 1692, John noted that “I expect my girl Betty and her aunt Jane from Chelsey this morning to sitt for her picture”.27 It would appear that, despite noting in his earlier letter that the painter Mr Earle, whom he had considered for the commission, would be absent from London for another month, he had gone ahead with arranging for his daughter’s portrait to be painted. This leads to the question of whether Lenthall was selected for the task instead and, as part of the same commission, might also have painted the portrait of his new wife and Peregrine.28

26The portrait of Mary Lawley and Peregrine Tyam, and the second picture of Elizabeth Baker, have become touchstones for the small number of works attributed to Lenthall. In December 2000 a portrait of a young boy holding a bow with a dog standing beside him, attributed to Lenthall, was sold at Christie’s in London, while a portrait of Mary Butler, the Duchess of Devonshire, in the collection of Hardwick Hall was also previously attributed to the artist (figs. 10–11).29 A portrait of “Mr Brand”, sold at Christies in April 1991, is described as having a label on the reverse that reads “Mr Brand/Lenthall pint”. In this portrait, Mr Brand is also depicted alongside a dog wearing two collars around its neck. The collars are inscribed “Hampton Court March 7 1671” and “Hampton Court May 6 1671” (fig. 12).30 These dated inscriptions, and the style of Mr Brand’s dress in the portrait, suggest that Lenthall was perhaps well established by the time he was commissioned by John Verney.

29

The two Claydon portraits attributed to Lenthall share compositional similarities with many other portraits of women of this period and echo three-quarter-length poses used by artists such as Peter Lely and, later, Willem Wissing and Jan van der Vaart. The portrait of Elizabeth Baker, which may date to around 1696 and her wedding to John Verney, shows her feeding a lamb with her left hand. Peter Lely frequently depicted female sitters with the attributes of a shepherdess in the 1670s when demand for his work necessitated that he repeat postures in studio production.31 The portrait of Elizabeth Baker bears a particularly striking resemblance to a portrait of Elizabeth Montagu by Willem Wissing (with the assistance of Jan van der Vaart). Although Baker does not hold a shepherdess’s crook, her right elbow rests on an elevated ledge at the same angle and she feeds a lamb flowers with her left hand. It is possible that Lenthall worked alongside artists such as Lely and Wissing, and adopted these poses in his own work, but there is no documentary evidence for this and it may be that he saw such compositions through their publication as mezzotints. John Smith’s engraving of Wissing’s portrait of Elizabeth Montagu was published by Thomas Bowles in 1688 (fig. 13).

31

The depiction of Peregrine Tyam in the Claydon portrait has many of the typical features of portraits of the period, which represented Black individuals alongside White female sitters. He stands at the edge of the picture, partially obscured by Mary Lawley who is seated in front of him. The slight tilt of his body and his raised hand suggest a sense of movement, almost as if he has just entered the scene, perhaps to deliver a message. As in many other similar portraits of this type, Peregrine is looking towards Mary, while she looks outwards to meet the gaze of the viewer. The condition of the portrait makes it difficult to fully make out his dress, but he seems to be wearing a swathe of green or gold silk across his arm, possibly over a red and blue livery.

John Verney, notably, chose to include Peregrine in the portrait with his new wife rather than in any of the portraits of himself commissioned over his lifetime. The positioning of the two figures in the composition, and the absence of any physical point of connection, suggest a lack of intimacy between Mary and Peregrine. The motivation for including Peregrine in the portrait may have been either John’s or Mary’s desire to commission a portrait in the fashionable style of depictions of other courtly ladies of the period, which showed White aristocratic women with young Black attendants.

Another interpretation is that the portrait represented an opportunity for John Verney to commission a portrait on the occasion of his marriage to demonstrate his wealth and material status, with both Peregrine Tyam and his wife representing valuable assets. This argument is enhanced by the presence of the jewel worn by Mary Lawley that he had given her as a wedding present.32 The gift was described by John in a letter to his father written on 7 July 1692, three days before the wedding: “I did yesterday carry her a Jewell and told her I designed her another but she should have it tho after marriage in what she liked best, this Jewell cost me formerly 98 pounds & was a Paire of Pendants but now I made it into a Breast Jewell, the alteration cost me 8 pounds”.33 The representation of this valuable wedding present in the portrait marked the celebration of the marriage as a union that brought John financial gain, with both Peregrine and Mary represented as signifiers of his status and wealth.

32Symbols of Enslavement

When the portrait is seen as a display of John Verney’s wealth and social status, clearly Peregrine Tyam’s presence must be understood both as a valuable possession, an enslaved Black servant representing a fashionable consumer good of the period, and as a visual signifier of Verney’s career status and ambition within the Royal African Company, with whose operation he was closely connected at the time the portrait was painted. Like many of the Black children and young people represented in British portraits of the seventeenth and the first half of the eighteenth centuries, Peregrine Tyam is depicted wearing a silver collar around his neck. The inclusion of the collar highlights his enslavement and emphasises Verney’s involvement in colonial affairs. David Bindman has argued that “the occasional presence of a slave collar around the neck of an extravagantly dressed black boy” was the only “direct hint of the cruelties of plantation or chattel slavery” in such attendant portraits.34 It should be noted, however, that these collars were pictorial references not only to the physical oppression of chattel slavery in the Americas and the Caribbean but also to the experience of enslavement in Britain at the time.

34The material survival of these collars, which had to be unlocked with a key, together with documentary evidence, suggests that enslaved people living and working in British homes were made to wear them. A court record from the Old Bailey dated 13 January 1716 recounts how Anne Smith and Jane Evans stole a silver collar from a Black boy called Richard who was in the service of a William Jordan. They persuaded the boy to let them break the collar off when he was out on an errand for Jordan and subsequently sold it.35 Adverts in contemporary newspapers calling for the return of men, women, and children who had escaped from their enslaver’s households sometimes included the collar as part of the freedom seeker’s physical description. In May 1703 the Daily Courrant advertised for the return of a fifteen-year-old boy called Pompey who had escaped from the home of the merchant William Stevens in Rotherhithe “with a brass Collar about his neck”.36 It is possible that the silver collar worn by Peregrine Tyam in the portrait was something that he was made to wear in reality, a symbol of John Verney’s wealth and business affairs but also a marker of his ownership of Peregrine and a physical restraint to deter escape or kidnapping. Its inclusion in the portrait gives us an insight into his status in the Verney household.

35Throughout this article, I have referred to the young male figure in the portrait as Peregrine but acknowledge that this was very likely not the name he was given at birth and lived with the for the first six years of his life. The Latin derivation of the name Peregrine means “one from abroad” and sometimes “wanderer”, and perhaps Verney selected this name with Peregrine’s African origins in mind. The name Tyam (sometimes spelt in the records as Tiam) is possibly a West African name. Thiam is a name found in Senegal and neighbouring countries today, and it is also possible that it referred to his place of origin. The parish register that records Peregrine’s death in 1707 noted that he was “a native of Tiam in Guinea in Africa sent to the Right Honorable the Lord Viscount Fermanagh”.37 Tiam is located in the Saint-Louis region of Senegal, an area called Upper Guinea by the British in the seventeenth century.

37As a result of the research of Phillip Emanuel, and his extensive work on the Royal African Company records, we now have a much clearer sense of how and when Peregrine Tyam was brought into John Verney’s household. A letter from the Royal African Company to Alexander Cleeve, a company agent in Gambia, in early March 1687/88 states: “We have given Leave for you to send home a black boy by this shipp to M.r John Verny one of our members”.38 This letter clarifies that Peregrine came from somewhere in Senegambia, with his name pointing to potential origins in modern day Senegal. Despite the fact that many company letters survive only as excerpts, Emanuel has found evidence of a significant number of boys sent directly to Britain from Africa by the Royal African Company as gifts for high profile members and investors. Surviving Company documents from between 1672 and 1714 record twenty-three children sent from Africa in addition to ten from the Americas, all but two of these children were male.39

38The wording of the excerpted letter to Cleeve also highlights that Company officials closely controlled the sending of enslaved African children as gifts during this period, a clear recognition of the social status associated with Black attendants at the time. The fact that officials had given clearance for John Verney to be sent a boy emphasizes his standing in the Company. Verney served on the African Company’s governing board intermittently for around eighteen years. In 1679 John Verney owned 700 shares in the company, and he held the role of assistant from 1679 to 1681, from 1686 to 1688, from 1691 to 1692, and from 1696 to 1697.40 It appears he acquired Peregrine from the company during a period in which he held this role. His father, Ralph, was clearly pleased with his son’s position, as he expressed in a letter to John in December 1692: “Your employment is so good at the Africa House that I think you do well to continue”.41

40Whyman highlights an instance in 1680 when Verney was charged with investigating a delivery of enslaved people who had arrived in a “bad condition”, but states that otherwise he “never mentioned slavery in his letters”.42 This is not true, however, given the fact that there can be little doubt that Peregrine was enslaved. Enslavement in Britain may have taken a different form to enslavement on plantations but it was, nevertheless, enslavement. As Emanuel has argued, enslaved children such as Peregrine provided “an important and distinctively racialized symbolic labour for those who benefitted from the slave trade. Age, and in particular childhood, was an important criterion Englishmen used to adapt enslavement to a British context”.43

42While we do not yet know the precise date or details of Peregrine’s arrival, a letter written by John Verney to his father in May 1689, six months before Peregrine’s baptism at Claydon, suggests that he was already living with Verney in London, and that the latter had a clear sense of what his role in the household would be. John Verney wrote: “My footeboy Harry Woodward went yesterday to apprentice, I shall want him to send on errands whilst my Black boy is so smalle”.44 In September 1688, several months before this letter was written, Verney received a bill from a tailor for a new livery for “his footboy”.45 This might have been intended for Harry Woodward, but it could also indicate when Peregrine arrived at the Verney home.

44John Verney’s letter to his father emphasises that Peregrine’s role in the household was as a servant from the time of his arrival, although his formal status remained ambiguous. Given that we do not have details of his arrival, it is not known whether he was purchased by Verney or was a gift from a company contact. The description in the parish register entry that he was “sent” to John Verney may indicate the latter. From the available evidence, it is likely that he was enslaved, at least for the early years of his life with the Verney family, although later, as a young man, he received payments from John Verney.

Scholarship on the concept of slavery under English common law formerly focused on the ambiguity of the legal status of enslaved African people brought to England from the colonies. Miranda Kaufmann notes that, while colonial legislatures had laws that defined “slave status”, English law did not, and so there was confusion when enslaved African people who had been purchased by English men and women in the colonies were brought back to England.

The most famous legal case was that of James Somerset in 1772, when Lord Chief Justice Mansfield ruled that Somerset could not be transported against his will to the Caribbean by his enslaver. However, legal cases debating this subject stretch back as far as the sixteenth century. Kaufmann highlights a case of 1569 that was cited by Somerset’s defence, who argued that “the plain inference from it is, that the slave was become free by his arrival in England”.46 In these particular cases, the law ruled in favour of the enslaved people, but the legal history is far more complex. Throughout the seventeenth century several cases successfully argued for trover claims over the ownership of a number of Black individuals on the basis that these people were defined as “merchandise” and that this ought to be upheld because of their non-Christian or “infidel” status.47 George Van Cleve challenges the idea that arrival in England automatically meant emancipation for enslaved people and that their position in “near slavery” remained “very subordinate”.48

46More recently, this idea that the status of enslaved people in early modern England was ambiguous has been challenged by Holly Brewer. She argues that both Charles II and James II used the power of the English crown to influence judges to produce rulings that would, in practice, legitimise slavery in English common law and the concept of people as property in both England and the colonies over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Brewer argues that these rulings, which include the case of Butts v. Penny in 1677, demonstrate that “real slavery did exist” in England and that the Somerset case actually “attempted to overturn the common law of slavery in England itself”.49

49It appears that, at some point during the years in which Peregrine Tyam lived and worked for John Verney, he may have received payment for his services. An account book dated between 1700 and 1707 has a number of entries referencing Peregrine that could be interpreted as payment of wages. The earliest of these references is from September 1703, when Verney listed his expenses while on a visit to Bath, at which point Peregrine would have been around twenty years old. Previous references to Peregrine in the account book were for his food when travelling and various items of new clothing.50 The expenses listed for the trip to Bath include “Breeches and Stockings for Pere. T” and a payment to Mrs Child for “4 weekes diet for me & Pere and for his lodgeing”; a separate payment to Peregrine Tyam for 5s. is also listed.51 In August 1705 Verney noted a payment to Peregrine Tyam for 15s. and in August 1706 he made a payment of 10s. to “Peregrine Tyam my Blackmore”. In February of the same year he noted that he had “Given Peregrine” 4s.52

50These four payments are the only evidence found to date that show direct payments to Peregrine himself, and they amount to the measly sum of £1 14s. over a three-year period.53 This account book is clearly not a complete record of all Verney’s expenses across this time frame, and it is possible that he made other payments to Peregrine. As it stands, these varying and consistently small sums are not enough evidence to suggest an arrangement that might be described as a regular wage.

53Whether Peregrine was paid by John Verney is perhaps a secondary point when it comes to his status within the household. He was brought to England as a small child and was baptised with a new name that, at least in part, sought to erase the identity and culture of his birth. It is difficult to conceive of any scenario in which he acted through his own agency or had the freedom to leave.

The representation of Peregrine Tyam in the portrait of 1692 was likely an attempt by John Verney to highlight his career achievements and prospects as a key figure in the running of the Royal African Company. From one perspective, Peregrine was a symbol for Verney’s connection to the company, and was used in the portrait to represent the enslavement and oppression of the hundreds of thousands of African individuals that John Verney and his colleagues facilitated. In addition, however, features such as the silver collar that Peregrine is shown wearing must be read as an indicator of the realities of enslavement in Britain and as an insight into his lived experience in the Verney household.

Visibility and Agency: Peregrine Tyam in London

We cannot know for certain whether Peregrine Tyam was made to wear a silver collar when he worked for John Verney, but the Verney family correspondence makes clear that he was chiefly tasked with the public-facing duty of delivering messages, a role that would have made him highly visible within the Verneys’ social and familial circle. Both in commissioning the portrait and in reality, John Verney understood the social status that accompanied the possession of an enslaved Black person, and intended Peregrine to symbolise this status in both art and life.

Most of Peregrine’s time with John Verney was spent in London, and the family’s letters and account books provide us with glimpses into this life. Before inheriting the family title on the death of his father in 1696, John Verney lived mostly in Hatton Garden and, following his removal to Claydon in 1698, he continued to spend a good deal of each year in the capital.54 Initially he remained in Bloomsbury, before moving to Holborn and finally to Covent Garden after 1702. Peregrine was part of a larger Black population in London than he would have been during his time in Buckinghamshire. Black Londoners lived and worked in a variety of roles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and there are more than 700 records of people of colour who lived in London between 1600 and 1710.55 A significant number of these were children (often boys or young men) who were enslaved servants.

54The baptism and burial registers of each of the areas of London in which Peregrine Tyam lived with John Verney between the years 1689 and 1707 record the names of some of these individuals and often the households with which they were connected. The parish register for St Andrew, Holborn, which John attended while living at Hatton Garden, records information about a number of individuals. The parish register includes an entry on 21 April 1693 for the burial of James Mannell, who is described as “A Negro servt [servant] to my Lord Chief Justice Trebe [Lord Chief Justice Treby] from Hatt [Hatton] Garden”, and on 18 January 1703 Thomas Carter, who is also described as “a negro Sert [Servant] from Hatton Garden”, was buried.56 In 1684 the register of St Pancras parish church recorded the baptism of a mother and daughter, Margaret and Frances, who were described as “Two Blacks of my Ld [Lord] Baltimores”. In 1690 Charles Muddiford, “A Black of ye Dutchess of Albemarle”, was baptised at the same church.57 A painting by the artist Jan Griffier of the Covent Garden Piazza, where John Verney and his family lived after 1702, shows a young Black boy playing with a hoop and stick at the centre of the composition (figs. 14–15).

56

The Verney family letters provide an insight into the kinds of tasks Peregrine Tyam was given as part of the day-to-day life of the family. Numerous references show that he acted as a messenger for John Verney from a very young age, carrying letters for him across the city to other family members and to social and business contacts.58 One of John’s most frequent contacts was his father, Ralph, and, during periods when both men were in their London residences, Peregrine was often given the task of carrying messages between them. When in London, Ralph and John Verney lived relatively close together, in Hatton Garden and Lincoln’s Inn, but it is significant that Peregrine was first given this duty of messenger when he was less than ten years old and was often required to deliver messages further afield.

58On 5 October 1692 John Verney wrote to his father: “Sir, I send Perry to bring me word how you does and to Desire your company at dinner with me today”.59 The following month John sent Peregrine to his father’s house to collect a gift of some apples for which he sent his thanks.60 The letters suggest that Peregrine was also charged with the duty of reporting back to John the news he encountered on his various visits to family and other contacts. In a letter of 16 November 1692 John recounted to his father how an acquaintance had burst into tears on receiving a message from him that had been delivered by Peregrine. While the letter suggests that John saw Peregrine as a trusted source of news, he didn’t refer to Peregrine by name but called him “my Black”.61 This is particularly significant because John was writing to his father, who knew Peregrine, and generally referred to him in notes and letters as “Perry”, or occasionally “my boy Perry”, a name used both by John and across the Verney family in letters.62 The shortening of first names and pet names was widespread in the Verney family correspondence during the seventeenth century. Nearly every member of the family was referred to by a familial nickname. The shortening of Peregrine to Perry could be read as a sign of the familiar affection in which the Verneys held Peregrine. He was often the only servant of the household who was mentioned by name in the letters and other Verney documentary records of the period. In July 1693, for example, when planning a visit to Claydon, John Verney wrote to his father that “when I come to your house I shall bring with me my wife, two Girls Malley & Pegg, two maids, coachman & Perry”.63

59The passing reference to Perry as “my Black” to his father, who knew and used Peregrine’s name frequently, was, however, a clear reminder of his enslaved status in the household and John Verney’s sense of ownership of this child. In addition, it would appear that the dynamic between Peregrine and John was not always smooth. In responding to notes from his son that were delivered by Peregrine, Ralph Verney regularly made sure to emphasise that it was he who delayed Peregrine from returning, and encourages his son not to blame the boy for his lateness.64 On 12 September 1692 Ralph wrote a note to John: “I staid the Boy therefore you must not chide him”.65 In March 1693 he again wrote to his son: “I being busy when Perry came staid him here some time”.66

64This dynamic seems to have been a persistent issue that continued for years. It came to a head in March 1699, when Peregrine Tyam ran away from John Verney’s house in Hatton Garden following a disagreement about Peregrine staying out longer than John thought necessary on an errand to buy milk. On 18 March John wrote to William Coleman, the long-serving steward at Claydon. In addition to other matters of estate business, Verney spent a significant portion of the letter detailing the disagreement with Peregrine and the subsequent fallout. Verney relayed to Coleman that “Yesterday Perry stayeing all the morning out on a small errand just by onely to fetch 3 or 4 Quarts of milk for a whitepott as soon as he came in seing me angry (tho I have not strength to beate him) out of doors he went and is run away”. He went on to note that Peregrine was “being then half drunck for of late he keeps some very ill company and setts with shabby fellowes at the alehouse but never would to any body confess who his comrades be”, and claimed that “he has served me thus many times of late and I have often threatned him to have him beate but never yet hath it been done”. Given Ralph Verney’s notes to his son in previous years in which he advocated on Peregrine’s behalf, it would seem that Peregrine was afraid of John Verney’s temper despite the latter’s claims that he had never followed through on his threats of violence. It may be that Peregrine, now aged around sixteen, was testing the limits of his situation. Verney went on to tell Coleman that “I heare he was yesterday in ye afternoon with two fellowes at ye blew lattice near Holborn bridge drinking brandy and that he lay last night at ye Mitre alehouse in Hatton Garden but left it early in ye morning: I think it is a house of no good repute. Where he is rogueing today I knowe not. I feare he will be trapand on shipboard and soe sent away to ye West Indies where ye Rogue will fetch above 20 pounds”.67

67It is clear in the last sentence that John Verney’s greatest fear was that Peregrine would be kidnapped and sent to the Caribbean to be sold. His knowledge of Peregrine’s value for any such kidnappers highlights his insider knowledge of the trade in enslaved people, which he had no doubt gained from his work for the Royal African Company for so many years. It is possible that he himself had handed over money for Peregrine when he was a young boy. It is difficult to ascertain whether in this moment he was concerned for the personal safety of the young man who had lived in his house since he was a small child or for the loss of a valuable piece of property.

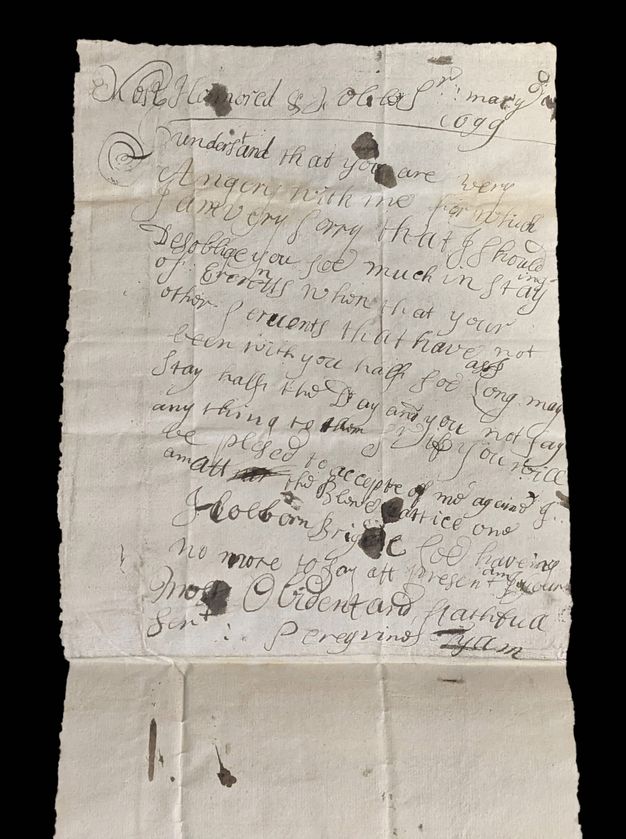

From this letter, we get one side of the story and, in many instances, that is all we can hope to find. The remarkable aspect of this particular case, however, is that the Verney archives also contain a note from Peregrine, written in what appears to be the days following their disagreement (fig. 16).

Most Honored & Noble Sr: March 1699

I understand that you are very

Angery with me for which

I am very sorry that I should

Desoblige you soe much in staying

of ererentts when that your

other servents that have not

been with you half soe long may

Stay half the day and you not say

anything to them Sr if you will

Be plesed to accepte of me againe I

Am att the Blewe Lattice one

Holborn Brige soe haveing

no more to say att present am I your

Most Obedient and faithfull

Peregrine’s words are largely contrite, and he indicates that he wishes to return to John Verney’s service. However, a sense of defiance also ripples through the note, in particular when he mentions the injustice that Verney’s other servants, who have not served him for as many years as Peregrine, get away with similar misdeeds.

It was not uncommon for enslaved people of colour living in the household of members of London’s gentry and merchant classes, in comparable circumstances to Peregrine’s, to attempt to escape and secure their freedom. Newspaper adverts of the period outline the attempts made by the men and women from whom these individuals had fled to regain their “property”. Simon Newman highlights an advertisement in the London Gazette on 10 September 1694, which describes “A Black Boy, an Indian, about 13 years old, run away … having a Collar about his Neck with this Inscription, the Lady Bromfield’s Black in Lincolns Inn Fields”.69 We cannot know whether Peregrine had originally intended to flee from John Verney’s household, but it seems that if he had he perhaps reconsidered relatively quickly, as he remained in Holborn, in close proximity to the Verney household. His apologetic letter suggests that he desired to return but whether this was after he had considered his options and weighed up the dangers of kidnap outlined by John in his letter to William Coleman we may never know.

69The letter provides us with an extraordinary glimpse into Peregrine’s experience in his own words. It also reveals that at some point he must have received an education where he was taught literacy. This presumably occurred during his childhood in John Verney’s service. It is clear from John’s first mention of Peregrine in his letter of May 1689 that he intended for the boy to take over as his messenger, and therefore it made sense for Peregrine to be able to read and write. Peregrine’s letter is confident and his hand is clear. It is significant that this young man, who spent his days delivering and collecting letters on John Verney’s behalf, saw a letter as the most appropriate form of communication to air his grievances and ultimately beg Verney’s pardon. The form of the letter echoes the countless missives that the latter sent to and received from family and society acquaintances, yet when Peregrine, like many other correspondents, signs off his note as “your Most Obedient and faithfull [servant]” the phrase’s meaning feels particularly loaded.

It should be recognised that, while the letter written in Peregrine Tyam’s own hand is an extraordinary documentary source, where a sense of his agency and voice is apparent, its survival, along with the additional details we have about his life, have been mediated through the archive of correspondence and records selected for preservation by John Verney, his owner.70 Peregrine’s letter, the biographical information that can be gleaned about his life, and his representation in the portrait all provide an opportunity to recentre the story of a young Black man in early modern England, yet the imbalance in the archive is impossible to ignore.71

70The Portrait and the Memory of Peregrine Tyam

It seems that Peregrine did return to John Verney’s household in March 1699. On 20 March a letter from John Verney to William Coleman includes the line, “Perry came again on Sunday and promeseth not to do so anymore”.72 For the next eight years his name continued to appear in Verney’s letters and account books with such frequency as to suggest that he was almost continually by Verney’s side. When Verney took his annual trip to Bath in the autumn, or on his frequent travels between London and Claydon, Peregrine appeared to have been one of very few servants always to accompany him and often the only individual mentioned by name. On one occasion he was recorded as having ridden Verney’s horse for him.73

72On 2 September 1707 Verney received a letter from his aunt Elizabeth Adams expressing her concern at the news that Peregrine was ill: “For my nnes [niece] Cary coming to town to see her brother … she told mee pery had bin very ill, which I was very sorry for, but I hope he is quit well Again, by this time, it is A very sickly tim in all parts, as I hear of & I hope youll let me hear from you sume times or els I shall fear you are sick two”.74 This letter was followed by a second, written by Elizabeth Adams on 23 September, confirming that Peregrine had died: “I heard by chance of ye death of poor Pery, which I am much concerned fearing you’l haveth a great mis of him he having bin long with you, & careful of you & knew all yr wayes & I am suer he had a trew love for you but Gods will must be submitted to in all things”.75 In the following weeks, John Verney received further letters that included messages of condolence from other members of the family, including a letter from Thomas Cave, the husband of his daughter Margaret: “I am very sorry for your Lordships loss in poore Perry, who I believe was very honest and a Real Lover of Your Family. I thank God both our little ones are very well as we hope their little Cousin is at Claydon”.76 Margaret herself also wrote to her father several days later, echoing her husband’s words: “I am extremely concerned for the loss of poor Perry he I believe being a true lover, of you, and the family, & and an old servant whom I feare you’le much miss, tho: I with otherway’s or that it were in my power to be serviceable to you which I’me allway’s ready and desirous to doe”.77 Ralph Palmer, the father of John’s first wife, Elizabeth, also sent his condolences: “I am sorry to hear that you have lost Perry”.78 In October 1707, the month following Peregrine’s death, John Verney’s account book recorded two payments for 24s. to John(?) Chaloner and 6s. 3d. to Elizabeth Hilder.79 Both of these expenses were listed as “for Peregrine”, and may have been a reference to nursing and burial expenses.

74Peregrine Tyam was buried at Middle Claydon church on 3 September 1707, the day after Elizabeth Adams wrote her first letter. He would have been around twenty-four years old, and had lived with and worked for John Verney for just over eighteen years. Comments on the health of his servants appeared quite often in John Verney’s letters. In 1692 he referenced the illness of his maid and coachman several times in correspondence with his father. In these cases, however, the comments seem to be related more to how their illness might affect the running of the household and whether he would have to take on additional servants to cover their duties while they were sick. Susan Whyman notes that “John’s letters were models of self-control, extremely pragmatic, and rarely revealed his feelings”.80 While we do not know whether John mentioned Peregrine’s illness and his death in his own letters, there is a tenderness in the manner in which his aunt, daughter, and son-in-law send their condolences. Perhaps some of their concern was largely related to the spread of illness more widely in the household, but there seems to be a sense that John was thought to be emotionally affected by the loss of Peregrine and that the latter’s ambiguous position in the family was regarded as distinct from that of other servants.

80John Verney died in 1717, since which the portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley appears to have remained in the collection at Claydon House. It was seen there by George Scharf when he visited the property in 1861. He did not sketch the portrait as he often did in his record of collections of portraits from around the country, but the extended entry on the picture in his notes indicates that Peregrine’s name had remained connected to the portrait and the story that was told about it.

81Mary daughter of Sir Francis Lawley & 2nd wife of John First Viscount Fermanagh. The black page who is looking over her shoulder is Peregrine Tiam, a man of Guinea brought to England by John Verney of Wasin uncle of the first Lord Fermanagh & baptised at Claydon when about 6 years of age. It is he who is also introduced into the conversation piece in the dining room. This lady died 24 August 1694. She wears a brown dress a blue mantle dark hair and brown eyes her r.h holds white flowers like Jessamen. The arms are in upper r.h corner.81

The source of Scharf’s information about Peregrine is unclear, but he may have learned Peregrine’s name from a Verney family member. This suggests that Peregrine’s memory lived on beyond his lifetime, even if his name was omitted from some records relating to the portrait, including the 1740 inventory.

On two notes, Scharf is incorrect. First, it is unlikely that Peregrine was brought to England by an uncle of John Verney’s. Secondly, the figure in the conversation piece that Scharf mentions is not Peregrine Tyam. The picture showing Ralph Verney (son of John Verney) and his family seated in the garden and waited on by a Black attendant was likely painted in the 1730s, more than two decades after Peregrine’s death.

This second picture, together with further documentary evidence, shows that Peregrine Tyam was not the only person of African heritage to have lived and worked at Claydon during the eighteenth century. Indeed, evidence suggests that at least four, and probably more, individuals lived at Claydon over this period, across generations of the Verney family. In the conversation piece picture, a young man dressed in livery turns to exit the scene at the very edge of the composition. Turning his face and twisting his body to glance back at the family group at the centre of the painting, he carries a tray on which he has presumably just delivered the tea that three seated figures hold in china cups around a table. Three further people stand in conversation on the lawn behind (fig. 17). From the date of the picture, it is likely that the painting depicts Ralph, 1st Earl Verney, and his family. In 1740, at the time the inventory was made, this picture was hanging in the drawing room along with the two portraits attributed to Lenthall. The document describes the picture as “The conversation piece of Ralph Lord Viscount Fermanagh his Lady with his Two Sons & Two Daughters”.82 The name of the young Black man depicted on the edge of the picture is so far unknown. He looks to be in his teens or early twenties, and is likely to have been an enslaved servant in the household of Ralph Verney.

82

Forty-seven years after the death of Peregrine Tyam in 1707, a baptism was recorded in the parish registers of Middle Claydon on 27 June 1754 for a three-year-old boy called Peregrine Grandison. His birthplace was given as Guinea, as it had been for Peregrine Tyam. The entry reads: “Peregrine Grandison a Native of Guinea; a Boy of Three Years Old and Servant to the Right Honorable Earl Verney”. It is very likely that he was enslaved, on this occasion in the household of Ralph Verney, second earl. Three years later, on 29 July 1757, presumably aged six or seven years, Peregrine Grandison died and his burial was recorded in the same register.83 No cause of death is given. It is striking, though not completely unexpected, that Peregrine Grandison was given the same name by Ralph Verney that his grandfather John had selected for Peregrine Tyam more than half a century earlier.84 It is less clear where the surname Grandison came from. It might have been a play on the word “grandson”, in creation of a link to the first Peregrine and John Verney, or it could suggest something of the boy’s origins: he might have been presented to Ralph Verney by a member of the Grandison family. The continuation of the name Peregrine also provides an interesting insight into how the memory of Peregrine Tyam had survived within the Verney family. Ralph Verney, the second earl, was born seven years after the death of Peregrine Tyam, whom his own father, Ralph Verney, the first earl (born in 1683), would surely have remembered well. When Peregrine Tyam was baptised at Claydon in 1689 he was around six years old, which makes the two boys the same age. The portrait of Mary Lawley and Peregrine was in the collection at Claydon during the brief time that Peregrine Grandison lived at the house. The presence of the portrait raises interesting questions about the recollection of Peregrine Tyam, and the preservation of his identity within the Verney family memory.

83Peregrine Grandison was not the last individual of African descent to live at Claydon while Ralph the second earl held the title. On 18 November 1789 one Thomas Whitby wrote to Mrs Cock the housekeeper, asking whether a servant at Claydon whom he describes as “ye Black” is trustworthy: “yr servant ye Black asked me ye price of Coals, as he wanted two Chaldron for a friend. Pray Madam May I Credit him; I shall take yr Advise how to act (I beg you’l say nothing to him about it”.85 The name of this particular individual is unknown, but this is strong evidence that Black servants continued to be present in the household at Claydon throughout the eighteenth century.

85Like his grandfather John before him, Ralph Verney, second earl, also had wider economic links to enslavement. He made “speculative purchases of West Indian lands” that possibly included enslaved people.86 As he and his wife did not have children, on his death in 1791 his holdings, including a mortgage on the Rhine plantation in Jamaica, passed to his niece Mary Verney, Baroness Fermanagh.87

86In the first volume of A History of the County of Buckingham, published in 1847, George Lipscomb writes that Ralph Verney, second earl, employed Black servants as musicians: “Lavish in his personal expenses and fond of show, he was one of the last of the English nobility who, to the splendour of a gorgeous equipage attached musicians constantly attendant upon him, not only on state occasions but in his journeys and visits: a brace of tall negroes with silver French horns behind his coach and six, perpetually making a noise”.88 Again, this anecdote provides nothing in terms of names or identifying details about the people in question, or when they might have been living at Claydon, but it does suggest that Ralph Verney, second earl, might have had a number of Black individuals as part of his household over the course of his life.

88Portraits like that of Peregrine Tyam perhaps provide only a fragment of insight into the experiences of Black people who lived and worked in the homes of the British elite during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In Peregrine’s case, his own letter provides an extraordinary, rare example of voice and agency within an archive preserved and curated for posterity by those who enslaved him. The insight we have into the relationship between Peregrine and John Verney is largely from latter’s perspective, and this dynamic and power imbalance should be acknowledged. However, as a historical source the portrait is a gateway through which we can begin to piece together some elements of Peregrine’s life with the Verney family. Both the portrait and the documentary glimpses of Peregrine’s daily life with the Verney family in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries emphasise that visibility played an important role. In the portrait he is objectified as a conspicuous symbol of John Verney’s material wealth and colonial career, a dynamic that reflected his daily life in his public-facing role of footboy and messenger. Peregrine Tyam’s appearance in the portrait—and its preservation in the collection at Claydon—kept his memory alive for the Verney family long after he died. His presence there has also acted as a catalyst through which other connected Black lives, such as Peregrine Grandison’s, have been revealed. Peregrine Tyam’s name was preserved by the Verney family through their meticulous keeping of records. For the vast majority of Black sitters in early modern British portraits this has not been the case. The portrait of Peregrine Tyam has demonstrated the vital importance of further research into depictions of as yet unknown Black sitters and its potential to restore the identities and experiences of erased individuals.

Acknowledgements

The preliminary research for this article was supported by a Research Continuity Fellowship awarded by the Paul Mellon Centre in June 2021. I would like to thank Nicholas Verney for his interest in the research and for generously allowing me to view the portrait of Peregrine Tyam and Mary Lawley at Claydon House. I am grateful to Sue Baxter and Gillian Mason for facilitating visits to Claydon and for sharing their expertise on the history of the property and the Verney family. I would also like to thank Charlotte Bolland, Jenifer Cooper, and Jo Langston for their encouragement and for pointing me in the direction of relevant source material. I am particularly indebted to Ed Town for his support and feedback throughout the research and writing process. I am grateful to the reviewers of this article for their suggestions and to the British Art Studies editorial team for their thoughtful comments.

About the author

-

Hannah Lee is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Warburg Institute. She completed her PhD at Queen Mary University of London in 2020 with a thesis exploring the representation of African people in Venetian decorative arts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Since completing her PhD, she has worked at the National Portrait Gallery and the National Trust for Scotland and is currently in the process of turning her thesis into a book.

Footnotes

-

1

Claydon House Archives, An Inventory of the Goods in Middle Claydon House Taken in November 1740, 4/7/83/1-4/13. ↩︎

-

2

Throughout this article I have capitalised the terms “Black” and “White” when referring to race and ethnicity to recognise both as historically constructed racial identities. ↩︎

-

3

Buckinghamshire Archives, Parish Register for Middle Claydon, PR_52/1/1/20. ↩︎

-

4

Susan Dwyer Amussen, Caribbean Exchanges: Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640–1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 192. ↩︎

-

5

Simon P. Newman, Freedom Seekers: Escaping from Slavery in Restoration London (London: University of London Press, 2022), 36; Slave Voyages, “Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade—Estimates”, https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates. ↩︎

-

6

David Bindman, “The Black Presence in British Art: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, in Europe and the World Beyond, part 1 of From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, vol. 3 of The Image of the Black in Western Art, gen. eds. David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), 256. ↩︎

-

7

Catherine Molineux, Faces of Perfect Ebony: Encountering Atlantic Slavery in Imperial Britain (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 24. ↩︎

-

8

Ibid., 28. ↩︎

-

9

Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 211. ↩︎

-

10

Beth Fowkes Tobin, Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-Century British Painting (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 30. ↩︎

-

11

Hall, Things of Darkness, 211. ↩︎

-

12

Ana Howie, “Materializing the Global: Textiles, Color, and Race in a Genoese Portrait by Anthony van Dyck”, Renaissance Quarterly 76 (2023): 612. ↩︎

-

13

Marcia Pointon, Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 146. ↩︎

-

14

Victoria Hepburn, “Naming Marcus: Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Portrait of Charles Stanhope, Third Earl of Harrington, and Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas”, Yale Center for British Art, https://britishart.yale.edu/naming-marcus. ↩︎

-

15

The names of the Black individuals depicted as attendants in earlier works, such as the groom in Paul van Somer’s portrait of Anne of Denmark, and the boys and young men shown alongside various aristocratic sitters in works by Van Dyck, are currently unknown. Jeremy Wood has identified the young boy in Van Dyck’s portrait of William Feilding, 1st Earl of Denbigh, as Jack, whom he argues Feilding probably brought to Britain from India. The portrait was painted in 1633–1634, but Wood’s contention is based a description in an inventory of the 1640s that refers to the portrait as “Vandick: My Lorde Denbeigh & Jacke”. Jack’s name is not included in other inventories. In listings of the portrait he is referred to as “a Blackamore” or his presence is not mentioned at all (Jeremy Wood, Buying and Selling Art in Venice, London and Antwerp: The Collection of Bartolomeo della Nave and the Dealings of James, Third Marquis of Hamilton, Anthony Van Dyck, and Jan and Jacob Van Veerle, c.1637–50, Walpole Society, vol. 80 [London: Walpole Society, 2018], 52). ↩︎

-

16

I am grateful to Edward Town for alerting me to this group of portraits by Willem Wissing. ↩︎

-

17

Molineux, Faces of Perfect Ebony, 31–32. ↩︎

-

18

Bindman, “The Black Presence in British Art”, 240. ↩︎

-

19

Susan E. Whyman, Sociability and Power in Late Stuart England: The Cultural Worlds of the Verneys, 1660–1720 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 68. ↩︎

-

20

Claydon House Archives, Account Book of John Verney, 4/7/36. ↩︎

-

21

The spelling of the name of the artist varies between Lentall and Lenthall. For consistency this article will refer to him as Lenthall except where quoted sources use the first spelling. ↩︎

-

22

Frances Parthenope Verney, Memoirs of the Verney Family During the Civil War, vol. 1 (London: Longmans, Green, 1892), 16. ↩︎

-

23

Guildhall Library, Register of Freedom Admissions, Showing Method of Gaining Freedom and Name of Master, Where Appropriate, CLC/L/PA/C/001/MS05668; Guildhall Library, Register of Apprentice Bindings: 1666–1795, CLC/L/PA/C/003/MS05669/001. ↩︎

-

24

J.D. Stewart, “John and John Baptist Closterman: Some Documents”, Burlington Magazine 106, no. 736 (July 1964): 308. ↩︎

-

25

Ellis Waterhouse, The Dictionary of British 18th Century Painters (Woodbridge: Baron Publishing for Antique Collectors Club, 1981), 222. ↩︎

-

26

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Palmer, 10 August 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

27

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 30 August 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

28

A portrait of Elizabeth (Betty) Verney as a young child is in the collection at Stanford Hall. The Courtauld Survey record of this portrait states that is signed by John Riley, who died in 1691, so it is unlikely that this is the picture in question, https://photoarchive.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/objects/431960/hon-elizabeth-verney-as-a-child-with-a-squirrel. ↩︎

-

29

The previous attribution to Lenthall is recorded on the National Trust online catalogue. The picture now has a more general attribution to “style of Willem Wissing” (National Trust, “Lady Mary Butler, Duchess of Devonshire (1646–1710)”, https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1129228. ↩︎

-

30

It is possible that the sitter in this portrait is Joseph Brand (circa 1605–1674), who was in the Salters’ Company and a member of parliament for Sudbury (History of Parliament. “Brand, Joseph (c.1605–74) of Tower Street, London and Edwardstone, Suff.”, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1660-1690/member/brand-joseph-1605-74). ↩︎

-

31

Catherine MacLeod, “‘Good but Not Like’: Peter Lely, Portrait Practice and the Creation of a Court Look”, in Catherine MacLeod and Julia Marciari-Alexander, Painted Ladies: Women at the Court of Charles II (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2001), 56. ↩︎

-

32

Adrian Tinniswood, The Verneys: A True Story of Love, War and Madness in Seventeenth-Century England (New York: Riverhead Books, 2007), 492; Amussen, Caribbean Exchanges, 60. ↩︎

-

33

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 7 July 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

34

Bindman, “The Black Presence in British Art”, 240. ↩︎

-

35

Proceedings of the Old Bailey, “Anne Smith. Violent Theft; Highway Robbery. 13th January 1716”, t17160113-18, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t17160113-18?text=t17160113-18. ↩︎

-

36

Newman, Freedom Seekers, 117, 122–23. ↩︎

-

37

Buckinghamshire Archives, Parish Register for Middle Claydon. PR_52/1/1/16. ↩︎

-

38

Royal African Company to Alexander Cleeve, 06.03.1687/88, The National Archives, T 70/50, 58v.; Phillip Emanuel, “‘[A]s Fast as Ships Return he Will Send Every one a Boy’: Enslaved Children as Gifts in the British Atlantic”, Slavery & Abolition, 44, No.2 (2023), 339. ↩︎

-

39

Ibid., 337. ↩︎

-

40

Whyman, Sociability and Power, 74. ↩︎

-

41

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 14 December 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

42

Whyman, Sociability and Power, 74. ↩︎

-

43

Emanuel, “‘[A]s Fast as Ships Return’”, 343. ↩︎

-

44

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 1 May 1689, Microfilm 636/43. ↩︎

-

45

British Library, Bill, 26 September 1688, Microfilm 636/43. ↩︎

-

46

Miranda Kaufmann, Black Tudors: The Untold Story (London: Oneworld, 2018), 6. ↩︎

-

47

Miranda Kaufmann, “English Common Law and Slavery”, in Encyclopaedia of Blacks in European History and Culture, vol. 1, ed. Eric Martone (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2008), 200–203. ↩︎

-

48

George Van Cleve, “‘Somerset’s Case’ and its Antecedents in Imperial Perspective”, Law and History Review 24, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 623. ↩︎

-

49

Holly Brewer, “Creating a Common Law of Slavery for England and its New World Empire”, Law and History Review (November 2021): 771. ↩︎

-

50

“Wairing things for Peregrin” (10s.) and “Linnen for Peregrine Tyam” (13s. 6d.) were recorded for 1700 (Claydon House Archives, Account Book of John Verney, 4/7/36). ↩︎

-

51

Ibid. ↩︎

-

52

Ibid. ↩︎

-

53

The account book does include payments to other servants and includes one reference explicitly described as the payment of wages that might be used as a comparison. In 1702 John Verney paid Elizabeth Wallis 9 pounds, 12 shillings, and 6 pence, and Jane Pain 9 pounds and 10 shillings “for wages”. It is not known whether these payments were made to two servants as annual wages or to more senior servants to be used to pay others. As a comparison, a domestic servant might be paid wages as low as £2 or £3 a year in addition to food, lodging, and clothing. A housemaid might receive between £6 and £8, and a housekeeper £15. A footman might get £8 a year and a coachman between £12 and £26 to cover their food, housing, and clothing (see Clive Emsley, Tim Hitchcock, and Robert Shoemaker, “Currency, Coinage and the Cost of Living”, Proceedings of the Old Bailey Online, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/about/coinage). ↩︎

-

54

Whyman, Sociability and Power, 57. ↩︎

-

55

Newman, Freedom Seekers, 39. ↩︎

-

56

London Metropolitan Archives Data Collections, Parish Register of St Andrew, Holborn, Project codes Z/PROJECT/BAL/C/P82/AND/A/010/MS06673/006/2 (James Mannell) and Z/PROJECT/BAL/C/P82/AND/A/010/MS06673/007/3 (Thomas Carter). ↩︎

-

57

London Metropolitan Archives Data Collections, Parish Register of St Pancras Parish Church, Project codes Z/PROJECT/BAL/M/P90/PAN1/001/1248 (Margaret and Frances) and Z/PROJECT/BAL/M/P90/PAN1/001/1249/A (Charles Muddiford). ↩︎

-

58

The Verney letters highlight that Peregrine took over the role of messenger from Harry Woodward, John Verney’s footboy. Documentary evidence suggests that enslaved Black men in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century London were often liveried personal attendants who ran errands and delivered messages. See the example of Jack Beef in Newman, Freedom Seekers, 11. ↩︎

-

59

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 5 October 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

60

“I have sent perry for the apples & giving you my thanks for them” (British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 29 November 1692, Microfilm 636/46). ↩︎

-

61

“I’m told when I sent my Black on Saturday to knowe how they did, that as soon as my Lady heard my name named she burst out a cryeing” (British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 16 November 1692, Microfilm 636/46). ↩︎

-

62

“Your letter my boy Pery delivered to Mr Crabb yesterday morning” (British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 7 December 1692, Microfilm 636/46). For a discussion of the difference between the British and American contexts of the term “boy”, see Newman, Freedom Seekers, xii. “Boy” and “girl” were used regularly in Restoration London to refer to employed young people “regardless of their race and status”, but in the American colonies the terms “could carry racist and derogatory meanings when used by enslavers to refer to enslaved children and adults” (ibid.)). John Verney also used the term with reference to his son Ralph Verney. ↩︎

-

63

British Library, Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 26 July 1693, Microfilm 636/47. ↩︎

-

64

This observation is also made by Tinniswood, The Verneys, 492. ↩︎

-

65

British Library, Letter from Ralph Verney to John Verney, 12 September 1692, Microfilm 636/46. ↩︎

-

66

British Library, Letter from Ralph Verney to John Verney, 12 March 1693, Microfilm 636/47. ↩︎

-

67

British Library, Letter from John Verney to William Coleman, 18 March 1699, Microfilm 636/50. The letter is reproduced here line for line. ↩︎

-

68

British Library, Letter from Peregrine Tyam to John Verney, March 1699, Microfilm 636/50. ↩︎

-

69

Newman, Freedom Seekers, 53. ↩︎

-

70

In a study of the life of Susannah Mingo, Jenny Shaw highlights that Susannah’s story, like that of “most women of colour of this period”, is visible only “because of her connection to a wealthy European man”, noting that “the sources that chart the contours of Susannah’s life were collected and maintained because they are the records of family, of inheritance and of genealogy” (Jenny Shaw, “In the Name of the Mother: The Story of Susannah Mingo, a Woman of Color in the Early English Atlantic”, William and Mary Quarterly 77, no. 2 (2020): 182). ↩︎

-

71

For further discussion on historical agency and the archive see Montaz Marché, “‘A Diamond in the Dirt’: The Experiences of Anne Sancho in Eighteenth-Century London”, in Many Struggles: New Histories of African and Caribbean People in Britain, ed. Hakim Adi (London: Pluto Press, 2023), 12. ↩︎

-

72

British Library, Letter from John Verney to William Coleman, 20 March 1699, Microfilm 636/51. ↩︎

-

73

Claydon House Archives, Account Book of John Verney, 4/7/36. ↩︎

-

74

British Library, Letter from Elizabeth Adams to John Verney, 2 September 1707, Microfilm 636/53. ↩︎

-

75

British Library, Letter from Elizabeth Adams to John Verney, 23 September 1707, Microfilm 636/53. ↩︎

-

76

British Library, Letter from Thomas Cave to John Verney, 29 September 1707, Microfilm 636/53. ↩︎

-

77

British Library, Letter from Margaret Cave to John Verney, 5 October 1707, Microfilm 636/53. ↩︎

-

78

British Library, Letter from Ralph Palmer to John Verney, 23 September 1707, Microfilm 636/53. ↩︎

-

79

Claydon House Archives, Account Book of John Verney, 4/7/36. ↩︎

-

80

Whyman, Sociability and Power, 39. ↩︎

-

81

National Portrait Gallery, Heinz Archive and Library, George Scharf Sketchbook 61, 1861, NPG7/3/4/2/72. ↩︎

-

82

National Portrait Gallery, Heinz Archive and Library, George Scharf Sketchbook 61, 1861, NPG7/3/4/2/72. ↩︎

-

83

Claydon House Archives, An Inventory of the Goods in Middle Claydon House Taken in November 1740, 4/7/83/1-4/13. A date of between 1730 and 1737 for this picture would be an appropriate fit for the ages of Ralph Verney (1st Earl Verney) and Catherine Paschall’s four children, who are depicted in the picture. This date range would place them in their early to mid-twenties. It is likely that the picture was painted before 1737, when John Verney, the eldest son, died aged twenty-six. ↩︎

-

84

“Peregrine Grandison a native of Guinea and Servant to the Right Honorable Earl Verney” (Buckinghamshire Archives, Register of Christenings, 1721–1812; Marriages, 1721–1750; Burials, 1721–1812 [Middle Claydon], PR_52/1/2). ↩︎

-

85

There is precedent among English aristocratic families for the dehumanising practice of giving the same name to enslaved African people who served in their households over multiple generations. The Sackville family at Knole reportedly gave a series of Black servants the name John Morocco (“A Catalogue of the Household and Family of the Right Honourable Richard, Earl of Dorset, in the year of our Lord 1613; and so continued until the year 1624, at Knole, in Kent”, in Vita Sackville-West, Knole and the Sackvilles (New York: G.H. Doran, 1922), 81). ↩︎

-

86

Claydon House Archives, Letter from Thomas Whitby to Mrs Cock, 18 November 1789, Verney 5/5/29/5. I am grateful to Sue Baxter at Claydon House for alerting me to this reference. ↩︎

-

87

Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, UCL, “Ralph Verney 2nd Earl Verney”, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146645389. ↩︎

-

88

George Lipscomb, The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham, vol. 1 (London: J. & W. Robins, 1847), 184. ↩︎

Bibliography

“America and West Indies: September 1672”. In 1669–1674, vol. 7 of Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, edited by W. Noel Sainsbury, 404–17. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1889. British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol7/pp404-417.

Amussen, Susan Dwyer. Caribbean Exchanges: Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640–1700. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Bindman, David. “The Black Presence in British Art: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”. In Europe and the World Beyond, part 1 of From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, vol. 3 of The Image of the Black in Western Art, gen. eds. David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates Jr., 235–70. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.

Brewer, Holly. “Creating a Common Law of Slavery for England and its New World Empire”. Law and History Review 39 (November 2021): 765–834.

British Library. Bill, 26 September 1688. Microfilm 636/43.

British Library. Letter from Elizabeth Adams to John Verney, 2 September 1707. Microfilm 636/53.

British Library. Letter from Elizabeth Adams to John Verney, 23 September 1707. Microfilm 636/53.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Palmer, 10 August 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 29 August 1688. Microfilm 636/43.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 1 May 1689. Microfilm 636/43.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 7 July 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 30 August 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 5 October 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 16 November 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 29 November 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 7 December 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 14 December 1692. Microfilm 636/46.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to Ralph Verney, 26 July 1693. Microfilm 636/47.

British Library. Letter from John Verney to William Coleman, 18 March 1699. Microfilm 636/50.