Between the Easel and the Mural

Between the Easel and the Mural: Ben Nicholson’s Large Abstract Panel Paintings for Modern Public Interiors in Early Cold War Britain

By Robert Burstow

Abstract

This article is the first sustained examination of Ben Nicholson’s short-lived engagement with architectural painting. It analyses the three commissions he completed between 1949 and 1952 for large abstract panel paintings in new, distinctively modern forms of public or quasi-public interior space, which, it is suggested, collectively contributed to the post-war, social-democratic reform of ideas of Britain and Britishness. The article traces the development of Nicholson’s thinking about the ideal relation of modern painting to modern architecture from the 1930s through to the execution of his panels, and further into the 1950s, when, during years of significant artistic and political change, he called for new architectural painting to be given greater independence from architecture. His changing attitudes are compared to the diverse views of his commissioning architects and shown to owe more to his understanding of early Italian wall painting and American abstract expressionism than to the British mural revival or the international architect-led campaign for a new “synthesis” of the arts. After illuminating his early awareness of large-scale American painting and of Clement Greenberg’s concept of “a genre of painting located halfway between the easel and the mural”, the article argues that Nicholson’s panels exemplified a similar concept of a hybrid genre that side-stepped the heightened Cold War associations of easel painting with capitalism and mural painting with various forms of socialism, and presaged both the modernist retreat from the integrated mural and the ostensible depoliticisation of large-scale abstract painting.

Introduction

In the burgeoning interwar literature of modern British domestic interior design, the abstract paintings and reliefs of Ben Nicholson (1894–1982) were frequently recommended to middle-class homeowners as appropriate decoration for domestic spaces.1 It was not until after the Second World War, between 1949 and 1952, that Nicholson undertook commissions for public or quasi-public interiors requiring large-scale paintings for particular architectural spaces. The resulting “panels”—as Nicholson invariably referred to them—were then among the largest abstract paintings in Britain and among the first abstract paintings to embellish modern public spaces. Their modernity reinforced the democratising values that underlay the new types of leisure and working space for which they were commissioned, reflecting the reformist politics of Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour governments. These well-paid commissions were awarded by distinguished British architects during a period of rapid expansion in corporate and public arts patronage and must have been gratefully received at a time when the art market was in contraction. They demonstrate that Nicholson was willing not only to collaborate with architects but also, for a brief period, to undertake as many works for public architectural spaces as the most prolific of British muralists and sculptors.2

1The commissions coincided with international interest in large-scale modern painting. Shortly before Nicholson undertook them, two of the most influential anglophone supporters of avant-garde art had claimed that contemporary artists were turning away from the easel picture. In 1947 his close friend Herbert Read declared in the British magazine Horizon that “Cabinet painting is a defunct art, perpetuated by defunct institutions … [which are] part of the defunct tradition of capitalistic art”, and called for “commissions … [like] those the medieval artist received”.3 The following year, the New York-based critic Clement Greenberg, whose ideas also attracted Nicholson, argued in his essay “The Crisis of the Easel Picture”, published in the American journal Partisan Review, that “the ‘decentralized’, ‘polyphonic’, all-over” pictures of the United States’ most “advanced” painters, such as Jackson Pollock, were “capable of being extended indefinitely”.4 He claimed elsewhere that “the art of painting increasingly rejects the easel and yearns for the wall” or for “a genre of painting located halfway between the easel and the mural”.5 Within a few years, Nicholson had realised both Read’s expectation for modern paintings to be commissioned for specific architectural locations and Greenberg’s for them to be painted on a scale approaching the mural while retaining the mobility of the easel picture.

3Nicholson’s panels have to date received little collective critical attention, perhaps because they did not suit the emphasis in Greenberg’s later and more influential criticism for modernist painters to draw attention to the physical and formal aspects of easel painting, and have rarely been on public view in recent years.6 As such, this article re-examines the circumstances of each commission and the relationship between each panel and its intended interior, identifying a transition in Nicholson’s approach to architectural painting from an acceptance of decorative integration towards a greater expectation of autonomy. That transition is explained in relation to his contact with four disparate movements or types of large-scale painting: the British mural revival, the international campaign for a modernist “synthesis” of the arts, the wall paintings of early Renaissance Italy and the canvases of the American abstract expressionists. The article will demonstrate that the evolution of Nicholson’s approach followed Greenberg’s contemporaneous endorsement of the hybrid mural–easel picture and presaged the turn in British modernist painting of the late 1950s from the mural to the large-scale movable easel painting. Furthermore, it suggests that Nicholson’s and Greenberg’s short-lived desire to conflate the mural and the easel picture was driven by aesthetic and political concerns connected to the emerging Cold War, as these painting genres, along with abstract and realist styles of painting, accrued new significance through their association with competing political and economic systems.

6Nicholson’s Architectural Panel Paintings

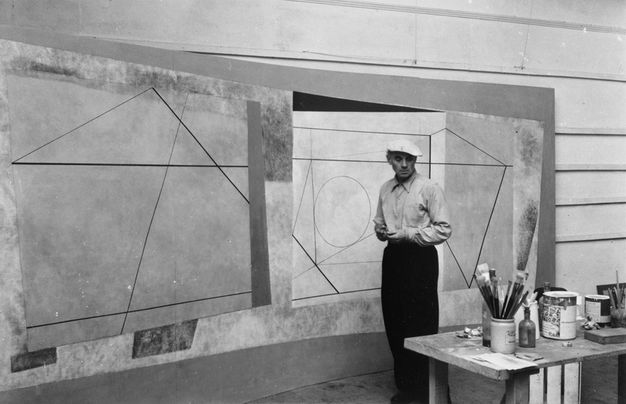

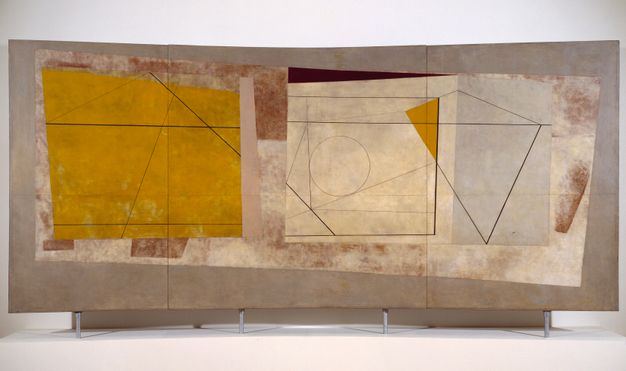

Nicholson’s first architectural commission, awarded in early 1949, was for a pair of six-foot-square concave panels to decorate a cafe on the MV Rangitane ocean liner, owned by the New Zealand Shipping Company.7 Founded by a group of colonial businessmen, the company had run passenger and cargo ships (named after Māori places) to and from Britain since 1873, although financial and operational control had long since been transferred to London and a dynasty of merchant shippers and bankers.8 Built on Clydebank by John Brown & Company, the Rangitane and its sister ship, the Rangitoto, were the largest liners the company ever owned and the first to be designed with single-class accommodation, making Nicholson’s panels accessible to over four hundred passengers on every voyage.9 The ship’s light, elegant contemporary-style interiors were the work of Howard Robertson from the London-based architectural partnership of Easton & Robertson. Nicholson was “fascinated” by the commission, painting his panels side by side and more or less simultaneously in his large new studio in St Ives in the autumn of 1949 (fig. 1).10 They are painted with thin layers of oil on board, the two panels sharing a restricted vocabulary of irregular, overlapping quadrilateral shapes that enclose areas of subdued, uneven colour and culminate in a single circle. The financial certainty of the commission allowed Nicholson to depart from the more saleable genres of still life and landscape, and to try out the more linear, colourful, and dynamic type of post-cubist abstraction he had developed in the 1940s on a larger scale, incorporating his new preoccupation with “off the rightangle composition” (fig. 2).11 Their original titles, Prelude and Intermezzo, invoked the harmonies of musical composition and their simple abstract geometries the ideal social harmonies sought by the interwar constructivists to whom Nicholson was close, including those associated with De Stijl, Abstract-Création, and Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art.12

7

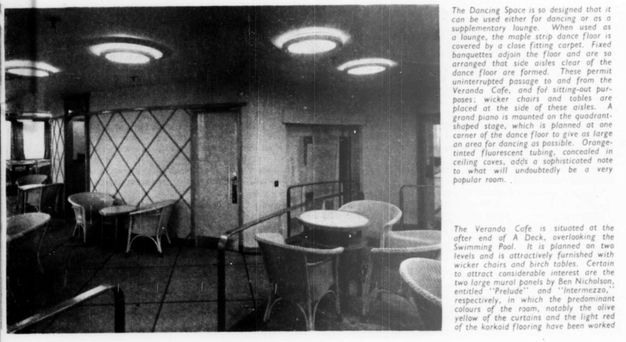

Nicholson supervised the installation of the panels in the Verandah Café at the aft end of the Rangitane’s principal deck of public leisure spaces in late January 1950 (fig. 3).13 Unlike the more conventional paintings and lithographs of pastoral and floral subjects ornamenting other public spaces of the ship, and the landscape murals decorating the corresponding cafe of the Rangitoto, his panels bore a clear visual relation to the cafe. Placed adjacent to its twin doorways, their concave surfaces echoed its curvaceous walls, ceiling lights, wicker chairs, and birch tables, while their geometry and muted colours reflected its orthogonal floor tiles and decorative treillage.14 The Architect and Building News observed that “These sensitive designs are in their composition and setting contributors to spatial effect”, noting that the architect had developed “to a higher degree [than in the Rangitoto] the aims guiding … the treatment of the public rooms”, especially in “the achievement of maximum space, and the effects of space”. The same commentator observed a play of continuity and contrast in the colouring of the panels and their surroundings:

1315the predominant colours of the room, notably the olive yellow of the curtains and the light red of the korkoid flooring have been worked into an engaging abstract pattern. The painting scheme for the rest of the room forms an unobtrusive background to these murals, being finished in off-white and pale pink; the servery wall … is painted pale buff.15

Given that the panels were installed only a few months after completion, it is unlikely that the cafe’s interior was designed with their specific forms in mind. The decorative unity of the cafe was, however, consistent with Nicholson’s pre-war diversification into the applied arts, and they bear a close resemblance to his near-contemporary design for a wool rug.16 His willingness for the mural panels to serve a decorative function would lead one of his later champions to castigate them as “mere decoration … abstract art without either critical direction or substantial content”.17

16Nicholson’s second architectural commission was for a large temporary self-service restaurant in the South Bank exhibition ground of the 1951 Festival of Britain. The Festival’s spectacular parade of British industrial, scientific, technological, and cultural achievement initiated by the Labour government was intended to reassert the nation’s position as a global power and exemplary democracy. Its director of architecture, Hugh Casson, and his design team acquired more than fifty murals and thirty sculptures for the South Bank through the Treasury-funded Festival Office in a concerted effort to integrate contemporary art into the exhibition’s pavilions, refreshment buildings, and outdoor spaces.18 Their selection reflected the embrace of modern art in the West during the Cold War as an ideological counter to Soviet bloc socialist realism, though, compared to the restrained and eclectic modernism favoured by Casson’s team, the Thameside Restaurant that housed Nicholson’s panel was an untypically “ultra-modern” structure commissioned from the architectural practice of the veteran British modernist Maxwell Fry and his partner Jane Drew.19 As lead architect, Drew hoped that the restaurant would contribute to a “peaceful and leisurely atmosphere … [where] visitors would get a slight rest from the excitement of the exhibition”, while its promise of “meals at popular prices” suggests that it was frequented by some of the least affluent of the exhibition’s eight and a half million visitors.20 The restaurant’s artworks were commissioned from Drew’s friends in the artistic vanguard—including Barbara Hepworth, Reg Butler, and Eduardo Paolozzi—and unlike most of the murals and sculpture in the exhibition were highly abstract, with no obvious thematic connection to the exhibition or their precise location (fig. 4).21

18

Nicholson’s colossal, free-standing panel was, however, integral to Drew’s architectural conception of the restaurant, and he discussed it with her long before it was formally commissioned.22 Mounted on a tubular metal frame, it screened seated customers from those queuing in the west entrance lobby for the self-service counter. For what remained his largest ever painting, measuring seven by sixteen feet, Nicholson was paid over £400, far in excess of the period’s standard fee of “thirty shillings a square foot”.23 Painted in oil-based household paints (probably to reduce costs), its three-part, asymmetrically curved hardboard support—with a curved central panel flanked by straight panels of unequal length—was constructed in London and dismantled for transportation to and from Nicholson’s studio in St Ives (fig. 5).24 While it replicated the concave surfaces of the Rangitane panels and reworked their contrast of a single circle against rectilinear shapes, this panel marked a significant departure in other respects: it was larger and more colourful, landscape rather than portrait in format, and more open, varied, and dynamic in composition (fig. 6). And, although Nicholson noted only that it had “a rather nice relationship with the river, … Waterloo Bridge … [and Hepworth’s] … slowly turning … abstract sculpture”, it went much further than his Rangitane panels in relating to its location: its concave form echoed the curving frontage and undulating roof of the building (itself designed to echo the meandering course of the Thames), while its floating planes of colour and geometric figures chimed with the triangular and circular tabletops, the “atomic” balls ornamenting chairs, and the slanting legs of the tables, chairs, and queue barrier inside Neville Ward’s and Frank Austin’s distinctive interior (fig. 7).25 That Nicholson’s abstraction, although untypical of Festival art, offered an appropriate expression of British modernity and democracy is suggested by the extensive support his work also received from the British Council in the early years of the Cold War, which nearly matched that received by Henry Moore.26

22

Nicholson’s third and final architectural commission came from the American publishing and media corporation Time-Life International for its new European headquarters on London’s New Bond Street (built 1951–1953). The building’s Austrian-born architect, Michael Rosenauer, had in the preceding thirty years designed major buildings in Vienna, London, and New York. These leased premises in the first large office block to be built in Britain after the end of the rationing of building materials provided spacious and luxurious seven-storey accommodation befitting the corporation’s wealth and prestige.27 They reflected the belief of its American founder and president, Henry Luce, in the importance of art and design to corporate success and national leadership.28 However, in an effort to prevent allegations of cultural chauvinism at a moment when the Korean War was making the strength of Anglo-American relations all the more important, Luce’s New York-based art adviser Francis “Hank” Brennan hired Hugh Casson and his former assistant on the Festival of Britain, Misha Black, to coordinate the design of the building’s interior, and they in turn commissioned work from fifty British artists, designers, and craftspeople (many of whom had contributed to the festival).29 Their combined efforts produced a more opulent, conservative, and heterogenous version of the “Festival Style” in its interiors, which some British commentators derided as a reflection of American vulgarity and excess but others regarded as “consciously and deliberately British in character”.30

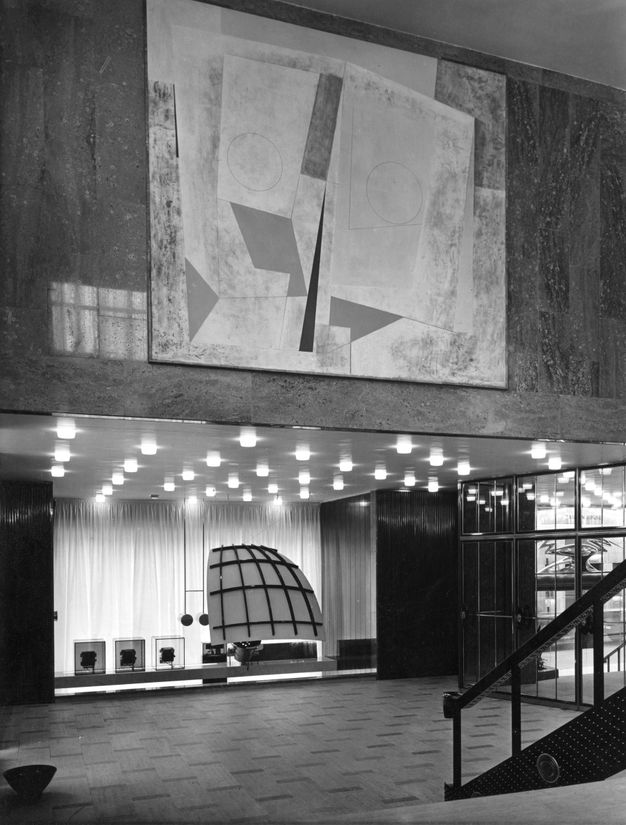

27Alongside modern sculptures from Geoffrey Clarke, Heinz Henghes, and Maurice Lambert, Casson commissioned Nicholson’s huge panel, measuring nine by ten and a half feet, which was only marginally smaller in surface area than his Festival panel (fig. 8).31 It was painted in oils in his St Ives studio in August and September of 1952, and installed that December.32 Its high placement on a polished grey-blue Derbydene marble wall—off centre at Nicholson’s request—in the lofty entrance hall housing the main staircase to the first-floor reception room made it visible from many viewpoints, a feature Nicholson enjoyed.33 Its dynamic vocabulary of bold angular and circular shapes floating over a mottled ground echoed the monolithic forms, textured surfaces, and precise detailing of the building’s lavishly finished interior (fig. 9). Although in a less public location than his Rangitane and Festival panels, it was accessible to company staff and visitors, and originally even to passers-by.34 Glimpsed at a distance from the open-plan reception room, it would doubtless have enhanced the domestic and informal character of this work-cum-social space (with its leather armchairs, standard lamps, full-length curtains, and rose-patterned carpet).

31

Alex J. Taylor has shown, that although Casson succeeded in commissioning works from several vanguard artists, Brennan often challenged his choices as he expected their works to have “corporate relevance” (an echo of the conservative coverage still accorded modern art in Luce’s Time and Life magazines, despite its increasing ideological utility in the United States).35 That the commissioners intended the panel to be “based upon forms in use in modern transport”, such as “the hull of a ship, the fuselage of an aircraft, etc” (reflecting the corporation’s international reach), may explain Nicholson’s conciliatory description of it on one occasion as a “mechanism”, and of elements within it as “cogs in the machinery”, although no such allusions are apparent in it or in any of his contemporaneous drawings or paintings. Indeed, he privately admitted that “through the sensitiveness & intelligence of Hugh Casson … I eventually had a free hand”, as his contract—paying him a princely £1,000 fee—broadly confirms:

3536The theme, character and form … are left to the artist’s discretion but it is suggested that the treatment should be kept simple, classical and spare in feeling, and pale and luminous in colour, so that it should not be too dominant an element within the hall. The artist is of course free to produce an emphasis within the panel wherever he may wish.36

In place of a preparatory sketch, an existing still life of Nicholson’s would be “regarded as an indication of the type of painting” to be executed, and a clause added by Nicholson freed him to “use a construction purely non-representational”, as this was what he “probably (though not certainly)” would do.37 Nicholson’s and Casson’s discomfort with Brennan’s and Luce’s prescriptive approach (and perhaps with Luce’s well-known staunchly Republican political sympathies) may explain Nicholson’s later remark to Read that his panel “cannot surely be in the least what T-L really want?”38 Read himself, whose anarchist leanings led him to loathe American “big business”, felt Nicholson’s panel was “the one redeeming feature in a terrible hodge-podge” and presumed there must have been “many difficulties with the American overlord”.39 Casson and Black were “very happy with the design”, except for what they saw as some technical defects, which Nicholson viewed as irrelevant to its overall effect and refused to adjust:

3740I rather think that when it is in position & the hall completed that it will create so much space and light (at least I hope this will be so) that the life of the thing will be visible & the particular Cambridge/Slate blue you mention will then fall into place— To alter it’s [sic] tone or colour would actually alter also it’s [sic] shape & it’s [sic] tension & so alter the whole construction. It is quite a formidable process to achieve, to obtain the precise colour, tone, shape in relation to the whole.40

The licence afforded Nicholson allowed him to produce a work with the autonomy of an easel painting: unlike his Rangitane and Festival panels, and indeed many mural panels, this panel was framed and mounted proud of the wall, conspicuously declaring its potential mobility. Its framing and mounting were conceived at a much later stage of the architectural design process than the Rangitane and Festival panels, and an early sketch by Casson suggests that a large easel painting rather than an integral mural had initially been envisaged.41 Yet Nicholson did not ignore the panel’s relation to its architectural setting and was evidently highly conscious of the effect of its forms and colours.

41Nicholson and the British Mural Revival

Although Nicholson did not describe his large panel paintings as murals, their size and architectural function placed them in the tradition of the mural. The year before Herbert Read called for painters to be awarded more commissioned work, the prolific German émigré muralist Hans Feibusch had noted in his book Mural Painting that “the interest in mural painting is reviving among architects, painters and the public”.42 His international survey of murals stressed that they belonged to a tradition that stretched back through the Renaissance to antiquity. The revival was only the latest in a series of resurgences that had begun in the 1840s and had received impetus from the Arts and Crafts movement and the modern movement.43 During the interwar years, murals had become increasingly common in modern and period interiors inhabited by the social elite, both in the drawing rooms of large country houses and upmarket London apartments and in the exclusive lounges and dining salons of luxury hotels and ocean liners. In the ten or fifteen years preceding Nicholson’s commissions, the Cunard and Orient lines had regularly patronised British artists, and Nicholson himself had been (unsuccessfully) recommended to join more than forty artists who made “decorative work” for Cunard’s Queen Mary (1931–1936).44 Murals had also been commissioned increasingly by commercial and civic patrons for spaces frequented by those who were less privileged, such as offices, shops, showrooms, factories, town halls, libraries, entertainment buildings, and churches. And, as a wider variety of patrons emerged, modern subjects and styles gained prominence, especially in modern interiors. Among them were precedents for Nicholson’s commissions for corporate and public spaces, such as John Armstrong’s murals for Shell Mex House in London (which pre-empted Time-Life’s intended theme for Nicholson’s panel) and Edward Wadsworth’s for the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea.45 Unlike Nicholson’s, however, these surrealist-derived murals reflected a shift of taste since the 1920s, whereby, as Clare Willsdon has observed, murals had become “an aid to ambience or mood”, with a tendency towards more light-hearted subjects.46

42In the years immediately after the Second World War, as Attlee’s Labour governments increased taxation of the rich and encouraged the democratisation of the arts, the mural moved decisively into the public realm. A growing number of commissions were awarded by ecclesiastical, industrial, commercial, and public patrons. Nicholson contributed to a broader trend in which murals were acquired in unprecedented numbers by local authorities for schools and social housing schemes, by development corporations for new towns and by the state for the Festival of Britain. He was also one of sixty British painters invited by the Arts Council to undertake large paintings on canvas for a touring Festival exhibition that it was hoped would be purchased by “the new collective patrons of the future”—“municipal authorities, educational bodies, captains of industry, [and] public utilities”—and thereby “find homes in a new church, a modern liner, the offices of the national Coal Board, the hotel lounges of British Railways, the waiting-rooms of airports, [or] the foyers of cinemas”.47 Although Britain’s post-war murals were rarely political in content, they were by and large intended to enrich the lives of so-called ordinary people. Yet, unlike the often more socially engaged murals of the 1930s, many of which were painted by members of the Artists’ International Association who were influenced by communist murals seen in Mexico, the United States, and the Soviet Union (which in some instances had been co-painted by them), post-war murals tended towards blander subjects and more decorative styles.48 There could be resistance and controversy, however, if patrons or cultural managers imposed the “advanced” tastes of the metropolitan middle classes on the wider public. Of the Arts Council’s sixty putative mural-sized canvases for the Festival, only three—all of them figurative—were acquired by the type of patron they had been intended to attract.49

47Few murals as abstract as Nicholson’s panels had been painted in Britain by 1951, public or private, and none of the more well-known ones survive.50 Nicholson was conscious that the popular response to his own mural panels might be unfavourable, joking anxiously to Drew that the pebbled “ha-ha” protecting his Festival panel from public reach could provide ammunition for those who disliked it.51 Even his large canvas for the Arts Council—an abstracted but recognisable still life—was caught up in the press and parliamentary storm that erupted around the abstract works commissioned from public funds for the Festival, leading Manchester’s councillors to subsequently veto its purchase by the city’s art gallery.52 If his more abstract architectural panels did not encounter similar hostility, it was probably only because the Festival panel was in a little publicised part of the South Bank and the Rangitane and Time-Life panels were not publicly funded.

50Although Nicholson’s panels were commonly described as “murals” and their locations were typical of those widely in use, Nicholson had little contact with mural painters or their institutions of training or support.53 His studies at the Slade School of Art forty years earlier were too early and too brief to have sparked his interest in architectural painting, and the Royal College of Art and the British School at Rome were then more prestigious centres of training for muralists. He seems to have had no contact with the Society of Mural Painters (founded 1939), although by 1950 its fifty members included some of his former associates in the British avant-garde, such as John Piper and Edward Wadsworth, and one of its guest exhibitors was his friend the abstractionist Victor Pasmore.54 If Nicholson neither saw himself nor wished to be seen as a muralist, it was perhaps because of the tendency in British muralism towards the light-hearted and frivolous.55 This would have been alien to his aspiration for art to embody spiritual and social ideas, nurtured by his early commitments to the Arts and Crafts movement, Christian Science, and constructivist art.56 Indeed, while working on the Rangitane panels he announced to his brother-in-law, the architectural historian John Summerson: “I find it a little difficult to work for a café-bar as I think I could go deeper into some idea for the equivalent of an 11th century Italian church”.57 And after completing the Festival panel he repeated almost the same thought to his first wife, Winifred, that he longed in his “architectural jobs” for “something a little more solemn, like a 11th or 9th or 6th century Italian church!”58 Such hopes would not have been unusual for a Rome scholar of the 1920s but were rare among post-war muralists. Nicholson’s interest in architectural painting seems to have been prompted less by the aims and ethos of the British mural revival than by the more socially oriented ideals of modern architects and their international campaign for what in 1944 Le Corbusier had called the new “synthesis of the major arts”.59

53Nicholson and the “Synthesis of the Arts”

As an enthusiastic supporter of the “new architecture”, Nicholson declared in 1941 that the best architects were “Le Corbusier, Gropius, Chermayeff, Lubetkin, Fry and Martin”, all of whom had collaborated with artists or, in the case of his friend Leslie Martin, had proposed how artists and architects might collaborate.60 The modern movement’s aspiration for the unification of architecture, painting, and sculpture had been encouraged by collectives and institutions such as De Stijl, the Bauhaus, and the Vkhutemas. Since the 1920s, the synthèse des arts majeures or arts plastiques had been enthusiastically endorsed by modern architects and artists, especially in France and Italy, and extensively discussed at meetings of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). CIAM’s senior figures, above all, Le Corbusier, José Luis Sert, and Sigfried Giedion, campaigned for the synthesis with renewed intensity after the Second World War, through conferences, publications, and a commission on “mutual collaboration” (1947–1953).61 Giedion’s summary of the CIAM conference of 1951, hosted by its British chapter, the Modern Architectural Research (MARS) Group, and timed to coincide with the Festival of Britain, declared that “the architect should employ contemporary means of expression and—wherever possible—should work in cooperation with painters and sculptors”.62 The conference charged artists with producing appropriate “symbolic forms” to assist “the humanisation of urban life” and, in the face of international cold war, with using “forms of large scale expression free of association with oppressive ideologies of the past”, signalling the leadership’s preference for modernism over fascist neo-classicism or communist socialist realism.63 Other strands of CIAM belief, such as that the modern movement would restore the unity of the arts achieved in the Middle Ages, revive the spiritual and emotional dimensions of architecture, and demonstrate abstract art’s affinity with modern architecture, were reiterated at the peak of the campaign in Paul Damaz’s bilingual survey Art in European Architecture / Synthèse des arts.64

60The synthesis had been promulgated in Britain by former Bauhäuslers and Vkhutemas students such as Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Berthold Lubetkin; by the partnerships they formed with British architects such as Maxwell Fry; and through conferences and exhibitions organised by the MARS Group and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).65 Among British painters, Nicholson had played a prominent role in this initiative: he was a founding member of the Unit One collective of painters, sculptors, and architects (1933–1935), a participant in the MARS and RIBA exhibitions promoting the synthesis, an editor of Circle (which embodied the synthesis in its tripartite structure and cross-disciplinary editorship and authorship) and the only British painter to contribute a statement to that landmark publication.66 His smaller paintings and reliefs had been purchased in the 1930s for modern domestic interiors, and were commended by architects and architectural critics,67 while his Festival and Time-Life panels were among the few English murals included in Damaz’s survey.68

65The approach of artists and architects to the desired synthesis varied enormously, however. In the 1920s those aligned with constructivism had sought total physical integration: long before Read’s or Feibusch’s promotion of mural painting, De Stijl’s 1924 manifesto had bluntly declared that “painting without architectural construction (that is, easel painting) has no further reason for existence”, and Theo Van Doesburg’s Café Aubette (1926–1928) had famously realised that vision.69 By the 1930s, however, debate in Britain had exposed wide-ranging differences of view: while the constructivist Eileen Holding still argued for the full interdependence of “art and its surroundings”, for example, Read advocated “counterpoint” and “plastic contrast” rather than “ultimate fusion”.70 The concept of “constructive art” announced in Circle accommodated these diverse approaches, presenting the more moderate views of CIAM members such as Breuer, Fry, Giedion, and Le Corbusier alongside the uncompromising beliefs of Piet Mondrian, who vehemently opposed both easel and mural painting:

6971By the unification of architecture, sculpture and painting, a new plastic reality will be created. Painting and sculpture will not manifest themselves as separate objects, nor as “mural art” which destroys architecture itself, nor as applied art, but being purely constructive will aid the creation of an atmosphere not merely utilitarian or rational but also pure and complete in its beauty.71

Notwithstanding Mondrian’s stance, Circle’s pluralistic approach legitimised murals and free-standing sculptures, although for many there remained a clear hierarchy in the different types of synthesis. According to Damaz, Sert, for example, favoured art that is “integrated” into a building (i.e., integral to the architect’s conception) over art that is “applied” (i.e., derives from cooperation between the artist and architect within limits set by the latter) or merely “related” to it (i.e., in harmony with the architecture but retaining its independence).72 Likewise, Damaz contrasted the integrated mural favourably with the “over-sized” easel painting: the former is seen by a moving observer and rarely as a whole, is “partly contingent on the outside space that surrounds the painter” and “must be an integral part of the architecture”, whereas the latter is movable, is seen by “a fixed observer” from a privileged viewpoint, “independent of environment”, and “rests on its own merits”.73 From the 1930s, celebrated architects incorporated murals and free-standing sculpture into modernist buildings such as the Spanish Republic Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition and the headquarters of the United Nations in New York (1947–1952) and of UNESCO in Paris (1952–1958).74

72That Nicholson received no commissions from architects until 1949, despite their more flexible attitude towards architectural art, was perhaps because the leading commissioners in Britain (such as Wells Coates, Fry, Serge Chermayeff, Oliver Hill, Brian O’Rourke, and Eugene Rosenberg) tended to favour surrealist, expressionist, and neo-romantic art over constructive abstraction. Those who did eventually commission him held diverse expectations. The eldest, Howard Robertson, who had once been a pioneering supporter of the modern movement, had by 1949 been barred from MARS for being “too decorative and insufficiently modern” and welcomed into the upper echelons of the more conservative RIBA.75 By contrast, the younger Jane Drew embraced a thoroughgoing Corbusian-derived vision of aesthetic fusion that exceeded even Fry’s (who had previously commissioned work from Feibusch, Moholy-Nagy, and Henry Moore). As a pre-war graduate of the progressive Architectural Association Schools, an active member of CIAM and MARS, and a collaborator with Le Corbusier, Drew had a more radical view of the synthesis, which was evident in her later comment on working with Paolozzi and Pasmore: “There was not a division in their minds or ours … Art had to be part of the same spirit of the building”.76 Like Drew, Nicholson’s third commissioning architect, Hugh Casson, was a child of the pre-war vanguard, a former pupil and assistant of Nicholson’s architect brother “Kit”, a member of MARS, and a friend of several modern artists. Unlike Drew, however, he retained an admiration for Beaux-Arts architecture and a scepticism of Corbusian theory; his sympathies were closer to the softer, anglicised modernism of the Architectural Review than to Le Corbusier, hence his more accommodating attitude to the independent mural panel.77 The diverse views of Nicholson’s commissioning architects account for their differing approaches to collaboration, to the point where each of his commissions may be broadly correlated with Sert’s hierarchy of the synthesis: where the Festival panel was integrated into Drew’s restaurant, the Rangitane panels were applied to Robertson’s cafe and the Time-Life panel related to Casson’s entrance hall. Nicholson’s willingness to accept their different approaches betrays his eagerness to work with architects but probably also his own shifting attitude to the synthesis.

75Nicholson’s conception of the role of abstract art in architecture had long been ambivalent. Andrew Stephenson notes that, while he accepted a popular perception in the 1930s that abstract art could be a “decorative addition to the modern home” (asking Coates on one occasion to let him try out his abstract white reliefs in “a severe rectangular white room”), his commitment to its purity and utopian associations made him resistant to its being seen as merely “decoration”.78 His early friendship with Mondrian may have encouraged many of his architect and architectural critic friends to perceive him, right into the early 1950s, as a proponent of constructivist integration and opponent of the mural. Martin singled him out in 1939 as an exemplar of revolutionary integrated artistic labour whose work would assist social integration:

78Nicholson … has moved consistently and intuitively towards a position in which his art becomes part of a synthesis of modern design … once the barriers between the “fine arts” and the “practical arts” are broken down, then the artist can take his place as a workman in the formation of a new culture.

Martin identified Nicholson’s work with constructivist possibilities for “the placing of paintings and reliefs in a modern setting”, not only on walls—fixed or even pivoting—but “as free standing screens where they may take up a functional position and act as a point of special emphasis” (just as his Festival panel would later).79 A similar view was advanced in a lecture of early 1951 by the art historian and critic A.C. Sewter, who acclaimed Nicholson as the pre-eminent living exponent of the new approach in which painters, in the service of architects, had become “research workers into forms and formal relationships”. Contradicting Feibusch’s claims in Mural Painting, Sewter argued that “those who believe in a possible revival of the art of mural painting are … doomed to suffer disappointment” because the mural tradition had been superseded by “certain kinds of abstract or Constructivist painting”. Yet by the time Sewter’s lecture was published in 1952, his claim that Nicholson was an exemplary constructivist had been fatally undermined by the relative autonomy of his Time-Life panel.80

79Unlike Mondrian, Nicholson had evaded the issue of architectural integration in his statement in Circle and, as Virginia Button notes, his reliefs of that period defied integrative ideals in being framed, while the unorthodox physical form of the Rangitane and Festival panels are rare in his oeuvre.81 Despite his participation in exhibitions promoting the synthesis and numerous contacts and friendships with those who attended meetings of CIAM and/or MARS—including Casson, Coates, Drew, Fry, Giedion, Martin, Pasmore, Summerson, Patrick Heron, Sadie Speight, and Kit Nicholson—Nicholson did not seem to have attended any himself. It is telling that the large-scale modern painting that he is known to have most admired was Picasso’s Guernica, which, although later hailed by Feibusch as “perhaps the most important work of modern mural art”, was a detachable canvas that Nicholson almost certainly first encountered on its tour of Britain, isolated from Sert’s Spanish Pavilion.82 That year, Nicholson told Summerson that only the best painters, such as Picasso, could work successfully on a large scale. After moving into Porthmeor studios, he hinted at his ambition to match Picasso’s achievement by announcing to his friend, the American abstract painter and critic George L.K. Morris, that he now had somewhere large enough to tackle a “‘Guernica’-sized painting”.83

81After completing his three mural commissions, Nicholson’s desire for more autonomous forms of architectural art only increased. In a lengthy and little-known statement drafted in the mid-1950s for publication in UNESCO’s Journal of World History (prompted, it seems, by his bid to win a commission for the organisation’s Paris headquarters), he now disavowed not only the constructivist vision of total integration but also the more flexible constructive and CIAM-driven concept of the synthesis.84 He reveals his concern that the growing involvement of architects in the commissioning of art had shifted authority away from artists, and blames contemporary architects for their inability or unwillingness to collaborate with artists (somewhat disingenuously, given his own insistence on independence):

8485In an integrated culture the architect will inevitably collaborate with the painter and sculptor wherever a public building is concerned … [However, t]he architect today through lack of an over-all conception is unable to conceive a building in this way and regards it as exclusively the concern of the architect or if he is slightly more enlightened he will call in the painter and/or sculptor at a very late stage in the conception of the building.85

He contrasted his own views with those of his now deceased friend Mondrian, arguing that the autonomy of painting and sculpture within architecture was essential to provide the freedom and imagination required for an enlightened way of life:

86I certainly agree with Mondrian that art should be an integral part of our surrounding life but I disagree with his conclusion that at that point “painting & sculpture will not manifest themselves as separate objects”. [I]n my opinion once we have [what Mondrian called] “actual plastic reality” then the free movable

object“separate object” can become an invaluable free & movable part of the creative imaginative changing & interchanging life within this plastic reality just as a pebble or a flower can be.86

His plea for art to remain “free” (i.e., abstract), “movable” and “separate” from architecture found favour with Read, one of the selectors of the UNESCO artworks, who, having seemingly also abandoned his earlier commitment to commissions such as those painted by the medieval artist, replied to him: “I agree about murals … I too would hate to live with an immovable work of art of any kind”.87 Nicholson’s wish for painting and sculpture to retain their independence from architecture marked a clear break from the approach he had adopted for Robertson and Drew and went beyond the “free hand” Casson had granted him. It resembled Henry Moore’s approach, who around the same time announced his preference for having sculpture outside a building, “in a spatial relationship to it”, rather than on it, believing that “sculpture must have its own strong, separate identity”.88 Such views were probably what led Damaz to lament the relationship between English modern architecture and sculpture in his survey of the synthesis, claiming that it “involves putting the two in harmony rather than any actual unification”, and to pronounce that “In England, good mural paintings are rare”.89

87Where Nicholson’s work had once offered a model of constructivist practice to a circle of younger London-based abstract artists led by Pasmore, his growing demand for autonomy now also distanced him from their ideals, which revived the constructivist aim to replace “fine artists” with “research workers” or artistic labourers in the struggle for social equality.90 (Indeed, in time, it was Pasmore rather than Nicholson who would more fully realise Mondrian’s, Martin’s, and Sewter’s vision of architectural integration.)91 Most significantly, Nicholson’s gradual retreat from seeking constructivist integration followed his wartime withdrawal from radical politics. Yet, paradoxically, the post-constructivist position Nicholson had adopted by the mid-1950s was encouraged at least in part by murals that Damaz and others habitually celebrated as exemplars of synthesis.

90Nicholson and Early Italian Wall Painting

Nicholson’s wish for greater autonomy in architectural painting was encouraged not only by his dismay at architects’ unwillingness to collaborate with artists and his admiration for mural-sized canvases such as Guernica but also by his reacquaintance in 1950 with early Italian wall painting. That year, as his interest in architectural painting grew, he interrupted his work on the Festival panel to revisit Italy with his close friend Cyril Reddihough, who showed a keen interest in his recent commissions.92 The art collector predicted that Italian frescoes would assist Nicholson’s evaluation of his own panels and that on their return “impressions of the trip [would] begin to germinate work”.93 With Nicholson’s costs partly met by the British Council, they toured Tuscany in Reddihough’s open-top sports car for about four weeks in late May and early June. Basing themselves in San Gimignano, they visited Pisa, Lucca, Siena, and Arezzo, before returning home via Ravenna, Padua, and Venice.94 One year after the trip Nicholson described it as “easily the most exciting holiday I’ve ever had”.95 Their itinerary—with its focus on Byzantine and late medieval and early Italian art, and conspicuous avoidance of the centres of the High Renaissance—reflected Nicholson’s love of the “Italian Primitives”, the painters of the Trecento and Quattrocento he had discovered through Roger Fry’s lectures at the Slade.96 His enduring admiration for them was doubtless reinforced by reading Fry’s publications, visiting Italy in the early 1920s, and becoming a friend of Adrian Stokes.97 In 1932 Nicholson commented that “the early Italians [had been responsible for] some of the most lovely ideas [to] have been expressed through painting and carving”.98 Read’s later observation that Nicholson, Hepworth, and Moore—who all spent time in Tuscany in the 1920s—and their artist friends “were living and working together in Hampstead, as closely and intimately as the artists of Florence and Siena had lived and worked in the Quattrocento” reveals their intense identification with early Tuscan artists and perhaps underlies his own poetic description of Guernica as a “great fresco”.99

92That Nicholson and his friends perceived an affinity between his work and early Italian painting is evident from several sources. In one of the articles that Nicholson commissioned and edited in the 1940s for the popular educational current affairs journal World Review, his friend and critical ally E.H. Ramsden observed that his work was often “inspired by the enjoyment of some Old Master, Uccello or [Piero della] Francesca, perhaps”.100 Other critic and curator friends, for example Summerson and Jim Ede, compared his paintings to those of Giotto, Uccello, Fra Angelico, and Piero.101 The comparisons were apt as these artists’ works, along with those of several early Sienese masters (notably Duccio, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Sassetta, and Francesco di Giorgio), figure prominently in his early scrapbooks and postcard collection.102 Among these postcards, photographs of the fresco cycles by Piero in the Basilica of San Francesco at Arezzo, by Lorenzetti in the council room of Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico and by Giotto in the Arena Chapel at Padua are especially numerous, all of which Nicholson revisited in 1950. He followed in the footsteps of many of Britain’s most successful interwar muralists in admiring such frescoes.103 They led Nicholson to the unusual conclusion, however—contradicting most proponents of the synthesis—that Piero’s frescoes at Arezzo and Giotto’s at Padua were “all entirely unrelated to the architecture”. Moreover, in his letter to his son Jake written soon after the trip he confided his ambivalence towards permanent integral wall paintings:

100104I am not sure that I like murals at all—if they are immovable—a good plain wall takes a lot of beating—though to put what one is feeling like having on it at that moment is something alive, but to get stuck with even a Giotto would drive me crackers … So really one wants a work conceived for & related to the architecture but movable.104

Here were the seeds of his later pronouncement for UNESCO’s Journal of World History that architectural artworks should be “movable”, “separate” objects.

Nicholson’s unconventional view may be explained by his intense attention to the internal formal dynamics of paintings, an attitude manifest in the articles he commissioned and edited for World Review, which compared modern paintings to those of the “Old Masters”. These articles reflected his familiarity with Roger Fry’s influential writings on the “Italian Primitives”, and just as Fry noted, for example, the “almost abstract forms” of Uccello, so Nicholson viewed historical paintings through the lens of modern painting.105 His new belief that murals should be “conceived for & related to architecture but movable”, and that some of the most celebrated historical wall paintings were “entirely unrelated to the architecture”, was significantly at odds with the orthodoxy of both CIAM and constructive art practices.106 Perhaps this encouraged his early interest in a very different form of large-scale painting, that of the American abstract expressionists, and in the writings of their foremost critical champion Clement Greenberg, who briefly sought in the late 1940s to reconcile the scale of their canvases with the autonomy and mobility of the easel picture.

105Nicholson, Abstract Expressionism, and Clement Greenberg

Nicholson was one of the first British artists to publicly praise the paintings of the abstract expressionists, describing them soon after they were first collectively exhibited in Britain at the Tate Gallery in 1956 as a “particularly healthy, free painting development”.107 This was an unusual view at a time when American art was still routinely regarded as inferior to European art.108 The large size of abstract expressionist paintings—typically far larger than that of their European counterparts—was a consequence of many of these artists having previously painted public murals for the Federal Art Project and/or assisted renowned American and/or Mexican muralists,109 as was well known to Greenberg.110 Nicholson was certainly aware of their work and of Greenberg’s commentary on it by the time he drafted his statement on art and architecture in the mid-1950s, and probably before then, as he worked on his own large abstract panels. Long before the transatlantic exchange of artists, critics, and curators became common in the 1950s, Nicholson’s friends Mondrian and Read had encountered abstract expressionist paintings in New York through their friendship with the collector and gallerist Peggy Guggenheim.111 They are certain to have known Jackson Pollock’s tellingly named Mural (1943–1944), an “immense painting” as Read later described it. Having been commissioned for Guggenheim’s apartment but frequently loaned for exhibition, it exemplified Greenberg’s vision of the hybrid mural–easel picture.112

107From 1948 onwards, other friends and acquaintances of Nicholson’s, notably the painters Alan Davie, William Scott, Peter Lanyon, and Patrick Heron, saw abstract expressionist paintings at first hand and met American artists and their critical supporters, including Greenberg.113 And, from 1950, Nicholson himself had opportunities to see their large canvases when he and Reddihough visited the Venice Biennale after their tour of Tuscany, and when Pollock’s work began to be shown in London.114 Nicholson was also informed of their critical success through his correspondence with George Morris, a leading member of the American Abstract Artists group and a former editor (circa 1937–1943) and contributor to the then Trotskyist journal Partisan Review.115 Although Morris mocked them as the “Squint & Blob” or “drip-and-dribble” school of painting, his letters to Nicholson affirmed that younger painters like de Kooning and Pollock were “in the ascendant” in New York, and occasionally enclosed copies of Partisan Review and other journals in which their work was featured.116

113As, from the 1940s, abstract expressionist painting featured increasingly in American and European journals of art and culture, and in mass circulation magazines distributed in London and Paris such as Time and Life, Nicholson gained many opportunities to study it.117 Most importantly, “advance notice” was given of it in Horizon, to which Nicholson subscribed throughout most of the 1940s and twice contributed articles.118 The work of these painters, especially Pollock, was praised by Greenberg and the British critic Denys Sutton in lengthy essays surveying contemporary American art.119 Nicholson’s interest would surely have been piqued, as he worked on the Rangitane panels, by Sutton’s observations that their paintings derived from “the American tradition of mural decoration” and was suited to modern architecture, and that Pollock had previously worked on public mural projects. After reminding readers of Herbert Read’s contention in an earlier issue of the journal that cabinet painting was “defunct”, Sutton asserted that “America still provides the possibilities of large-scale painting”, his certainty perhaps encouraged by familiarity with Pollock’s Guggenheim Mural and by the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Large-Scale Modern Paintings (1947).120 Such paintings offered Nicholson an alternative to the figurative, less formally adventurous, and less autonomous murals typical of post-war Britain, and he would surely have envied these American painters their freedom from the constraints commonly imposed on muralists by architects and patrons. It was soon after the publication of Sutton’s article that Nicholson announced to Morris that he now had a studio large enough to tackle a mural-sized painting.

117Through his reading of Horizon and Partisan Review Nicholson also came to know Greenberg’s critical writings. On one occasion he asked Morris to send a particular issue of the American journal as it contained an article by Greenberg.121 Although it is difficult to be sure of which articles he knew, it is probable that by the time he painted his panels he was familiar with Greenberg’s much repeated idea—hinted at in “The Crisis of the Easel Picture” (1948) and explicitly addressed in other articles published in Partisan Review that year and elsewhere the year before—that “the vehicle of ambitious art” was moving “beyond the easel, beyond the mobile framed picture, to the mural perhaps” or to “a genre of painting located halfway between the easel and the mural”.122 Greenberg’s claims were voiced tentatively, however, perhaps because associating modern painting with muralism risked breaking two of his critical taboos: aligning it, on the one hand, with decoration and thereby with what he perceived as a less serious aesthetic ambition, and, on the other, with political instrumentality, given the public mural’s frequent propagandistic uses (in the United States for example, by New Deal socialists, the American Communist Party, and the Popular Front).123

121Greenberg’s idea that large-scale modern paintings such as Pollock’s Mural occupied a “halfway state” between the easel and the mural positioned them in a fortuitous aesthetic and political middle ground at a moment of rising international tension between the communist and capitalist blocs.124 At this very moment (circa 1947–1948), Greenberg might be said to have himself been “halfway” between communism and capitalism, as he abandoned his Trotskyist allegiances for the anti-totalitarian liberalism soon to be extolled in Arthur M. Schlesinger’s The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (1949).125 Nicholson’s own wartime reorientation towards “liberal humanism”, after a brief flirtation with radicalism in the late 1930s, came a little earlier than Greenberg’s, but was part of the same widespread rejection of totalitarianism in Europe and North America, especially notable among artists and intellectuals, as described in Daniel Bell’s The End of Ideology (1960).126 By 1945, for example, following Naum Gabo’s lead, Ramsden had distanced Nicholson’s work from the communist associations of constructivism by suggesting that it should be described as constructive “not in any narrow or sectarian sense … but in the wider ethical sense in which a whole attitude towards life is implied”.127 When, in the years that followed, the Soviet Union blockaded Berlin and achieved atomic capability, and Mao Zedong founded the communist People’s Republic of China and faced United Nations forces in Korea, the “halfway state” of the hybrid easel–mural painting seems to have taken on a shared, if brief, attraction for Nicholson and Greenberg, perhaps as the artistic corollary to a more centrist form of political culture that might defuse the East–West ideological confrontation.

124Whether Nicholson’s enthusiasm for the large movable painting and declining faith in the integrated architectural mural was encouraged by Greenberg’s ideas or merely coincided with them, it seems to have produced a similar ambition. Although he would probably have objected to Greenberg’s increasingly narrow brand of formalist criticism (as did his friend Morris), he is likely to have shared Greenberg’s anxieties over both the representational content and decorative associations of murals, given his wartime disavowal of radical politics and longstanding ambivalence towards abstract painting’s decorative uses. Although public murals had rarely been deployed in Britain for political ends, Nicholson would certainly have been conscious of their uses by the international democratic and revolutionary Left.128 His own mural projects ran little risk of being seen as either decorative or politically radical, however, given the allegiances of his architects and patrons. Yet if Nicholson’s and Greenberg’s promotion of the hybrid mural–easel picture was intended to dissociate modern art from both capitalism and communism, they had seemingly abandoned this aim by the mid-1950s.

128By that time, as we have heard, Nicholson was calling for architectural art that was “movable” and “separate”, and implicitly divorced from the decorative function of the mural. Likewise, by then Greenberg was calling for clarity in relation to abstract expressionism on “where the pictorial stops and decoration begins”, and soon declaring more anxiously that “Decoration is the specter that haunts modernist painting”.129 So, although Nicholson’s early awareness of abstract expressionism and of Greenberg’s critical writings help explain his interest in large-scale panel painting in the late 1940s, by the time that most British middle-generation “followers” of the New York School, such as William Scott, Peter Lanyon, and Patrick Heron, caught up with these ideas Nicholson’s preoccupation with architectural painting had largely passed. His declining interest in the political agency of art in the 1950s also paralleled Greenberg’s, whose campaign to redefine “modernist” art in terms of disciplinary “purity” and formal autonomy ostensibly isolated it from the political realm, while paradoxically allowing it to be adopted by liberals as a symbol of freedom and democracy.130 In due course, Greenberg’s and Nicholson’s wariness of the decorative and leftist associations of the mural was taken up by an even younger generation of Greenberg’s British followers, who, in their commentary on the large, free-standing, abstract canvases presented at the Place and Situation exhibitions of 1959 and 1960, respectively, in London, emphatically detached them from the “decorative” contingencies and ambiguities of the mural, insisting on their status as “easel paintings” despite their “environmental proportions”.131 In distancing large-scale modernist paintings from the mural tradition and from fixed sites of display (ironically, given the exhibitions’ titles and the radical intentions of some of the exhibiting artists), their political implications were diminished and their commercial potential increased. For this younger generation of artists and critics working in an age of mass media, art’s relation to architecture was a less pressing concern than spectatorial intimacy and participation. Despite Nicholson’s apparent resistance to Time-Life’s appropriation of his mural for corporate purposes and his fantasies of decorating medieval churches, his desire for the autonomy of large-scale painting prepared the ground for its depoliticisation and consumption by the private collector, business corporation, and public museum.

129Conclusion

Nicholson’s architectural commissions contributed to a concerted attempt by the post-war political establishment to reform and modernise Britain and British identity in response to the growing international tensions of the Cold War, while maintaining the nation’s imperial and cultural prestige. Whether produced for the immediate benefit of socially diverse Antipodean travellers, working-class Festival goers, or the clients and staff of an American multinational, Nicholson’s panels were co-opted by states and corporations to signal British modernity and democracy. Although they originated in the propitious political, economic, social, and cultural circumstances of post-war “New Britain”, they remained outside the mainstream of the British mural revival and failed to gain popularity. And, although Nicholson was close to many architects who sought a humanising synthesis of the arts, his wariness of their priorities led him to step away progressively from constructivist forms of integration, as his own politics became less radical. Ironically, by the time the Architects’ Journal honoured Nicholson in 1958 as “one of the few painters to recognize the value of a closer relationship between the artist and the architect”, he had already moved towards enacting Sert’s weakest model of collaboration and what Damaz judged an inferior mode of “over-sized” easel painting.132

132If Nicholson was never as fully committed to the ideals of architectural integration as his constructivist allies claimed, the rationale for his position as he painted his panels was shaped by three central, if seemingly short-lived, convictions: that the high valuations of the most revered historical examples of wall painting were less dependent on their architectural surroundings than commonly believed; that the large-scale modern paintings of Picasso and the abstract expressionists offered a model for a genre of painting that conflated the easel and mural picture; and, lastly and perhaps least consciously, that the contrasting forms of painterly production associated above all with capitalism and communism might be reconciled through compromise. Nicholson’s preoccupations had, however, been increasingly overtaken in the 1950s by the responses of younger artists and critics to the hegemony of western capitalism and the ubiquity of its visual media, issues with which he refrained from engaging. His panels were essentially late expressions of inter-war values, though Cold War aesthetics gave their increasing autonomy new political significance.

Nicholson’s growing resistance to the idea of the architecturally integrated mural accompanied his declining political radicalism and made it more possible for the commercial value of murals to be compatible with the capitalist market and for them to survive if their locations were changed or destroyed. Indeed, it ensured the survival and monetary worth of his own panels when the Thameside Restaurant was demolished in 1962 and the Rangitane liner decommissioned the following year, although it gave Time-Life International an opportunity and incentive to attempt to sell its own panel when it vacated its premises in 1992.133 The Rangitane panels are currently in the hands of two different private owners, the Festival panel is in the collection of the Tate Gallery, and the Time-Life panel, which is still in situ, is visible only to the staff and well-heeled customers of a luxury French fashion retailer.134 Regrettably, the relationship of these panels to the interiors for which they were commissioned has been diminished or destroyed, and the intention of Nicholson’s architects—if not necessarily always of Nicholson himself or of his corporate clients—to install artworks that might be socially transformative has been compromised by their removal or by the curtailment of public access to them. Ironically, the panel least formally integrated into its setting is the only one still in place and we are now largely reliant on a handful of photographs to reveal the formal and spatial effects these architectural paintings once produced. Unsurprisingly, the Time-Life commission proved to be Nicholson’s last; in later life he accepted only two commissions for mural-sized works, both for free-standing sculptural reliefs set in landscape rather than painted panels in architectural interiors.135

133Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Lee Beard and Dr Chris Stephens for encouraging this research, the editorial staff and anonymous readers at British Art Studies for their insightful responses to my article, and my wife Helen for her unstinting support.

About the author

-

Robert Burstow is Associate Professor of History and Theory of Art at the University of Derby. He is a specialist in mid-twentieth century British art, with a particular interest in public sculpture and mural painting. He has published articles and reviews in Apollo, Art History, The British Art Journal, The Oxford Art Journal, and The Sculpture Journal, contributed chapters to Henry Moore: Critical Essays (Ashgate), Sculpture in 20th-Century Britain (Henry Moore Institute), Sculpture and the Garden (Ashgate), The History of British Art, 1870–Now (Tate and Yale Center for British Art), British Art in the Nuclear Age (Ashgate) and Péri’s People (Kunsthaus Dahlem, Berlin), and curated exhibitions for the Royal Festival Hall and Henry Moore Institute. He is a member of the Public Statues and Sculpture Association’s Public Sculpture of Britain board and a former postdoctoral fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Footnotes

-

1

See, for example, Roger Smithells and S. John Woods, The Modern Home: Its Decoration, Furnishing and Equipment (Benfleet: F. Lewis, 1936), 100, 105; J.L. Martin and S. Speight, The Flat Book (London: William Heinemann, 1939). ↩︎

-

2

Compare Nicholson, for example, to Edward Bawden, Barbara Hepworth, Barbara Jones, Henry Moore, Kenneth Rowntree, and Alan Sorrell. ↩︎

-

3

Herbert Read, “The Fate of Modern Painting”, in Herbert Read, The Philosophy of Modern Art (London: Faber & Faber, 1982 [1951]), 66, first published in Horizon 16, no. 95 (November 1947). ↩︎

-

4

Clement Greenberg, “The Crisis of the Easel Picture”, in The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. 2, Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 225, first published in Partisan Review 15, no. 4 (April 1948). Nicholson’s interest in Greenberg’s criticism is evident from his request for his American friend, the painter George L.K. Morris, to send him a recent issue of Partisan Review containing an article by Greenberg (Morris, letter to Ben Nicholson (hereafter BN), 12 February [1942], Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.1.2.3039). ↩︎

-

5

Clement Greenberg, “Review of Exhibitions by Worden Day, Carl Holty, and Jackson Pollock”, in Greenberg, Collected Essays, vol. 2, 201, first published as “Art” in The Nation 166, no. 4 (24 January 1948); and “The Situation at the Moment”, in Greenberg, Collected Essays, vol. 2, 195, first published in Partisan Review 15, no. 1 (January 1948). ↩︎

-

6

For Greenberg’s later views see, for example, “Modernist Painting”, in Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 85–94, first published in Forum Lectures 1, no. 2 (1960): 2–3. ↩︎

-

7

BN, letter to J. Leslie Martin, 1 February [1949], Sir Leslie Martin Personal Archive, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (my thanks to Alice Strang for bringing this and other letters from BN to Martin to my attention). ↩︎

-

8

W.A. Laxon et al., Crossed Flags: The Histories of the New Zealand Shipping Company Ltd and the Federal Steam Navigation Company Ltd and their Subsidiaries (Gravesend: World Ship Society, 1997). ↩︎

-

9

See Laxon, Crossed Flags, 88–89; “Passenger Accommodation on the ‘Rangitoto’”, Builder 77 (9 September 1949): 322. ↩︎

-

10

BN’s photographs of each panel bear captions on their reverse indicating completion by September 1949, despite their later titles (Ben Nicholson Photo Albums labelled St Ives, 100–200, nos. 193 and 194, 94–95, Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.5.1.2). Their ordering and titles in BN’s photo albums suggest that the slightly larger one (on the left in the studio photographs), may have had slight chronological precedence. Their collection from his studio on 27 October is recorded in BN, letter to J. Leslie Martin, 28 October [1949], Sir Leslie Martin Personal Archive, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, and in BN’s letter to George L.K. Morris, 6 November 1949, George L.K. Morris Archive, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian, Washington, DC, cited in Sarah Jane Checkland, Ben Nicholson: The Vicious Circles of his Life and Art (London: John Murray, 2000), 439n24. Lewison dates BN’s move into Borlase Smart’s former studio as “sometime before early November” (Jeremy Lewison, Ben Nicholson (London: Tate Publishing, 1993), 246) but the dates on the photos of the Rangitane panels place the move possibly as early as September, unless the panels were started elsewhere. For BN’s “fascination” see BN, letter to J. Leslie Martin, 28 August [1949], Sir Leslie Martin Personal Archive, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. ↩︎

-

11

BN, letter to E.H. Ramsden, 11 July 1945, cited in Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 224. On BN’s more saleable genres see Chris Stephens, “Ben Nicholson in War Time”, in A Continuous Line: Ben Nicholson in England, ed. Chris Stephens (London: Tate Publishing, 2008), 57–63. ↩︎

-

12

Their original titles appear in handwritten notes on the reverse of photographs in Nicholson’s photo albums; on the album page, they are given in handwriting as “1949 (Prelude)” and “1949 (Intermezzo)”, following BN’s later titling system (BN Photo Albums labelled St Ives, nos. 100–200, 94–95, Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.5.1.2). ↩︎

-

13

See BN, letter to John Summerson, 26 October [dated 1949 by Alan Bowness], Sir John Summerson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 20048 (uncatalogued); my thanks to Chris Stephens for bringing this letter to my attention. On their installation see BN, letter to George L.K. Morris, 29 January [1950], Morris Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian, Washington, DC, cited in Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 227, 246. Both panels must have been trimmed by as much as six inches on each side when installed since the dimensions recorded on the reverse of the photos in Nicholson’s photo albums are larger than those given in Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 170, and in Norbert Lynton, Ben Nicholson (London: Phaidon, 1993), 234, pl. 218. ↩︎

-

14

See “M.V. Rangitane: Interior Design of the Public Rooms”, Architect and Building News 197 (27 January 1950): 91–97; “The ‘Rangitoto’”, Building 24 (October 1949): 355. For more on October 1949 (composition-Rangitane) (i.e., “Prelude”) see Christie’s, London, Modern British and Irish Art Evening Sale, sale catalogue, 25 June 2014, lot 31. For more on October 1949 (Rangitane) (i.e., “Intermezzo”) see Christie’s, London, Modern British and Irish Art Evening Sale, sale catalogue, 22 March 2022, lot 14. ↩︎

-

15

“M.V. Rangitane”, Architect and Building News, 91–93. ↩︎

-

16

See Lynton, Ben Nicholson, 235, fig. 220. ↩︎

-

17

Charles Harrison, “Ben Nicholson and the Decline of Cubism”, in Since 1950: Art and its Criticism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 66. ↩︎

-

18

See Festival of Britain, Festival of Britain 1951, South Bank Exhibition: Catalogue of Exhibits (London: HMSO, 1951). ↩︎

-

19

See Iain Jackson and Jessica Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 132–37. ↩︎

-

20

Quotation from Jane Drew is from “The Festival of Britain 1951”, 1989, 4, Fry & Drew Papers, 21/7, Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Collections, London. For the restaurant’s prices see Ian Cox, The South Bank Exhibition: A Guide to the Story It Tells (London: HMSO, 1951), 91. ↩︎

-

21

See Jane Drew, “The Riverside Restaurant”, in A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain, 1951, ed. Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier (London: Thames & Hudson, 1976), 103–4. On art in the South Bank Exhibition see Robert Burstow, Symbols for '51: The Royal Festival Hall, Skylon and Sculptures for the Festival of Britain (London: South Bank Centre, 1996); Robert Burstow, “Modern Sculpture in the South Bank Townscape”, in Festival of Britain, ed. Elain Harwood and Alan Powers (London: Twentieth Century Society, 2001), 95–106. Drew had met Nicholson through the collector E.C. (“Peter”) Gregory, who loaned her one of the two Nicholson pictures he had bought in the autumn of 1943 (E.C. Gregory, letter to BN, 11 October 1943, Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.1.2.1418). ↩︎

-

22

On BN’s early plans see BN, letter to J. Leslie Martin, 28 August [1949], Sir Leslie Martin Personal Archive, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Drew’s early restaurant plans, dated December 1949, include a “curved feature”, and Chris Stephens notes that the idea was “hatched” in 1949; see Chris Stephens, “Ben Nicholson, Festival of Britain Mural” (manuscript for Tate Gallery Catalogue entry), n.d.; Chris Stephens, letter to David Lewis, 3 July 2000 (my thanks to Chris Stephens, former curator for modern British art at Tate Britain, for bringing these documents to my attention). For the commissioning date of June 1950 see Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 246. It is unclear when exactly he began work on the panel but it was finished in January 1951 and installed that April. ↩︎

-

23

For BN’s fee see Jane Drew, “The Festival of Britain 1951”, 1989, Fry & Drew Papers, RIBA Archive, 21/7. Drew increased the fee out of her own pocket when BN argued that the panel’s curved surface made it fractionally larger. For the standard fees see D.F. Jenkins, “John Piper: The Englishman’s Home, 1950–1951”, in Alan Powers et al., British Murals and Decorative Painting, 1920–1960: Rediscoveries and Interpretations (Bristol: Sansom, 2013), 291. ↩︎

-

24

See “Examination of Structure and Condition of Ben Nicholson Festival of Britain Mural” by the Tate Gallery Conservation Department, 10 April 2001; Chris Stephens, “Ben Nicholson, Festival of Britain Mural”, unpublished and undated notes (my thanks to Chris Stephens for giving me access to these documents). Drew later claimed that the idea of a curved panel was hers and was discussed only after BN and Hepworth had separated (i.e., circa 1950) (Jane Drew, “The Festival of Britain 1951”). However, given that BN had already executed the Rangitane panels, it seems likely that he and Drew had discussed the idea earlier than she recollected and perhaps that the idea had been partly BN’s. ↩︎

-

25

BN’s quotation is from his letter to Fred [Staite] Murray, 1 May [1951], Murray Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 876.5.37 (my thanks to Chris Stephens for bringing this letter to my attention). ↩︎

-

26

Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 70–83. ↩︎

-

27

On Rosenauer see Michael Rosenauer, Michael Rosenauer, Architect (1884–1971): Vienna–London–New York (London: Gallery Lingard at the Building Centre, 1998; exhibition catalogue: Nordico Stadtmuseum, Linz, 1988), 4, 33–34; Cythia Fischer (ed.), Michael Rosenauer, Linz–London, ein Brückenschlag der Architektur (Linz: Nordico—Museum der Stadt, 2004), 147. On the building itself see Ian McCallum, “Prestige and Utility: Time-Life’s London Offices”, Architectural Review 113, no. 675 (March 1953): 172. ↩︎

-

28

See Alex J. Taylor, “Diplomatic Devices: Henry Moore and the Transatlantic Politics of the Time-Life Building”, Sculpture Journal 29, no. 1 (2020): 21–22. ↩︎

-

29

See Taylor, “Diplomatic Devices”, 11. On Casson’s role see “London Newest Building”, Architectural Forum 99 (August 1953): 111. For more on the art and craft commissions see Richard Cork, “Towards a New Alliance”, in Eugene Rosenberg and Richard Cork, Architect’s Choice: Art and Architecture in Great Britain since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1992), 14–15; and Tanya Harrod, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 352–54. ↩︎

-

30

See Taylor, “Diplomatic Devices”, 22; Lionel Brett, “Towards the New Vernacular”, Design, no. 51 (March 1953): 13. ↩︎

-

31

On Casson’s involvement see his letter to BN, 13 June 1952, in Time-Life Archive, cited in Checkland, Ben Nicholson, 280n50. Casson had known BN since the 1930s when he had been a student of BN’s architect brother Kit, and later a member of his architectural practice (Helena Moore (ed.), The Nicholsons: A Story of Four People and their Designs (York: York City Art Gallery, 1988), 13–15, 27, 52–53). ↩︎

-

32

On the medium see Lynton, Ben Nicholson, 240. It is identified as tempera by Cork, “Towards a New Alliance”, 14, and in Eugene Rosenberg’s photographs, 14799 and 14800 in the RIBA Collection, but there is no evidence to support this. On the key dates see Lewison, Ben Nicholson, 246; Checkland, Ben Nicholson, 280. ↩︎

-

33

For BN’s request see his letter to Casson, 15 June 1952, Sir Hugh Casson Papers, National Art Library / Archive of Art and Design, 2008/2/5/1/5. On its multiple viewpoints see BN, letter to Herbert Read, 14 January [1953], Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.1.3.66. ↩︎

-

34

See BN, letter to Herbert Read, 14 January [1953], Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.1.3.66; Cyril Reddihough, letter to BN, 19 May [1955], Ben Nicholson Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, 8717.1.2.4016. ↩︎

-

35

On Brennan’s interventions see Taylor, “Diplomatic Devices”, 19. ↩︎

-

36